Inflation and Rising Bond Yields Will Hit the ECB’s Pain Point

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Investors concerned about inflation rearing its capital-eroding head are demanding higher yields in the bond market. But this rise in government borrowing costs, at a time when nations have loaded up on debt to defend their virus-stricken economies, poses a challenge for the European Central Bank, with Italy particularly vulnerable to a financial squeeze.

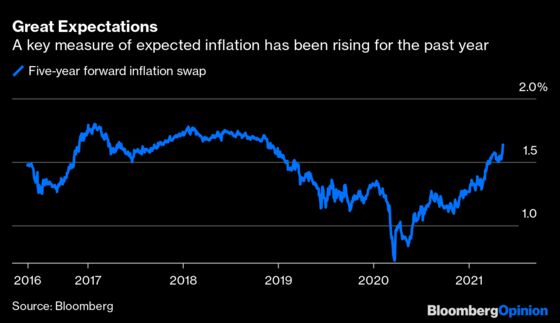

Markets are anticipating that the combination of fiscal and monetary stimulus will finally stir consumer prices from their lengthy slumber. In the euro zone the five-year forward inflation swap, used by the ECB to gauge expectations, has recently climbed to 1.6%, its highest level in more than two years. This year’s average of 1.4% is the strongest since 2017’s 1.65%.

In response to this changing economic outlook, Italy’s 10-year borrowing cost has more than doubled in the past three months, surpassing 1% to reach its highest level in nine months. It’s climbed at twice the pace of benchmark German debt levels, which are themselves close to rising above zero for the first time in two years. France started paying to borrow for decade-long debt earlier this year.

The easy trade in Europe this year has been betting on a compression of the spread between Italy and Germany by owning the debt of the former — the euro zone’s most liquid and highest-yielding country — and being short that of the latter, which has the most negative-yielding bonds. That bet works brilliantly when yields are falling, but it swiftly unravels when the opposite occurs. A rapid repositioning by bond traders threatens to exacerbate Italy’s interest-rate woes.

Even at its current elevated level, Italy’s 10-year borrowing cost is well below the 2018-2019 average of 2.25%. Those were painful times for Europe’s third-largest economy and biggest debtor — and were supposed to be firmly in the rear-view mirror. Yet until the EU’s Recovery Fund cavalry turns up sometime later this year, Europe’s weakest link remains vulnerable.

It is totally within the ECB’s grasp to show it has Italian premier Mario Draghi’s back: The bank can step up its weekly bond purchases to help close the spreads or at least keep them contained.

ECB President Christine Lagarde promised at the March meeting to substantially increase the speed of bond buying, and repeated that pledge at April’s press conference. The next quarterly economic update on June 10 will involve an ill-timed review of the pandemic purchase program. The 500 billion-euro injection to increase the program to 1.85 trillion euros was only agreed to in December. But several governing council members want to call time on monetary stimulus before fiscal stimulus has even started, let alone begun to take effect.

To prevent the rise in yields getting out of hand, the ECB has got to accelerate its weekly bond buying to more than 20 billion euros. In the past week, the pace slipped again to 16.3 billion euros from 19 billion euros the week before, albeit reduced by large redemptions. That slippage risks re-igniting the debate about premature tapering that has been an unfortunate feature of ECB press conferences this year.

The central bank’s latest forward guidance has focused on ensuring what it opaquely calls “favorable financing conditions,” with much hullabaloo about a new “multi-faceted and holistic” approach. It is hard to decipher what this comprises, but for certain the critical element is underlying government borrowing costs.

The recent government bond rout is already filtering through to real-economy corporate financing. Some 80% of new investment-grade bonds sold this year by non-financial companies trade below their issue price, our Bloomberg News colleague Tasos Vassos reported on Friday. Investors burned by those price declines will demand higher yields on future sales.

The ECB needs to make sure the current market realignment does not get out of hand, especially when it has all the available tools to prevent it. In 2018, for example, the 10-year Italian yield jumped to 3.75% in October from 1.75% in May; a replay of that magnitude would be an epic disaster for the nation’s finances. Lagarde needs to swiftly display leadership akin to Draghi’s “whatever it takes” mantra.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.