Where George Floyd Died, Immigrant Businesses Are Suffering

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Last week, I walked past the burned-out, fenced-off remains of the Third Police Precinct in south Minneapolis. After the death of George Floyd four months ago, rioters looted and torched the precinct and much of the surrounding Lake Street area, a five-mile stretch that’s home to many small, immigrant-owned businesses. The precinct remains vacant, even as the rest of the neighborhood struggles back to life. The trashed Target store across the street is being rebuilt; a large white tent houses a temporary grocery store; demolition crews pull down the charred remains of an old brick building.

Elias Usso, a 42-year-old Ethiopian immigrant and pharmacist, opened his Seward Pharmacy last September on a busy block five minutes west of the Third Precinct. Standing behind his counter, Usso tells me that the business was holding its own right up until he received a phone call from his alarm company on the evening of May 27. He logged into the security cameras and watched as looters took things “like they work here.”

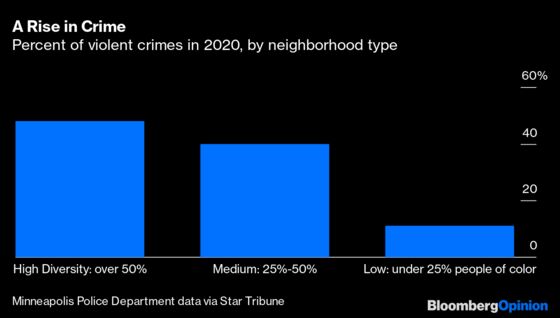

Insurance covered much of the repair. A GoFundMe campaign also helped. Usso decided to re-open his pharmacy on September 1, but the city’s turmoil has deterred customers and put his personal safety at risk. An analysis by the Minneapolis Star-Tribune found that, compared with the five-year average, robberies and property crimes are up 11% and serious assaults up 25% in Minneapolis. There have been 59 homicides in 2020, the most since 1998. The city’s most diverse neighborhoods, including those bordering Lake Street, are experiencing almost half of the reported incidents. Powderhorn Park, home to Seward Pharmacy, Usso’s home, and the corner where George Floyd was killed, has seen reported violent crime incidents surge almost 50% over the five-year average.

****

On Lake Street, Somali restaurants are located across from Hispanic-owned nail shops and just down the block from a decades-old Scandinavian general store. Throughout, Black businesses mingle with those founded by the city’s newcomers. Chicago Avenue bisects one of the busiest stretches. Head south on it seven blocks and you’ll reach the berms and barricades blocking what one sign declares is the “Free State of George Floyd.” One block further south, stanchions and flowers protect the spot where Floyd was suffocated by Derek Chauvin, an officer from the Third Precinct who’d received at least 17 civilian complaints against his conduct over the years.

For decades, the precinct has been known as a hub for some of the city’s worst cops and behavior, but the problems weren’t confined there. The 2015 shooting of Jamar Clark, an unarmed Black man, sparked an 18-day protests outside of the city’s deeply troubled Fourth Precinct. While some policing reforms happened — the department tightened its use-of-force policy — much remained undone. The Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis, an organization led by a lieutenant accused by the current chief of police of wearing a “White Power” badge on his motorcycle jacket, has long opposed efforts to investigate and discipline bad cops. Minnesota’s legislature could overrule these objections with law, but rural and suburban legislators have stalled progress.

Perhaps the greatest impediment to reform is a deeply ingrained, city-wide vanity that allows residents and leaders alike to paper over civic failures through encomiums to the region’s progressivism and civility. In 2017, the Department of Justice released a report praising Minneapolis for its “peaceful, measured response” to the Jamar Clark riots, noting that it “prevented the violence and riots seen in other cities following officer-involved shootings.” The state’s leading newspaper patted Minneapolis on the back, urging the city to improve communication, but said nothing about the underlying racial tensions that would destroy Lake Street businesses a mere three years later. Twin Cities activists never stopped advocating for police reform, but the city’s leadership largely folded up the policymaking tent.

The consequences were tragic. In the days following the Floyd riots, as the city and the country wondered what Minneapolis would do, the City Council failed to propose an actionable plan for reform, because it didn’t have one. Instead, after a week of violence, nine out of 12 city council members stood on a stage in Powderhorn Park, pledging to activists that they would “begin the process of ending the Minneapolis Police Department” despite the fact that “we don’t have all the answers about what a police-free future looks like.”

The council cobbled together a ballot proposal to eliminate the city charter’s requirement to maintain the current structure of the police department. The city’s Charter Commission wisely turned down the council. Among other objections, the commission noted that the ballot proposal was made in haste, especially during a crime surge. (Mayor Jacob Frey, Council President Lisa Bender, and two city council members I contacted for this article did not respond to interview requests.)

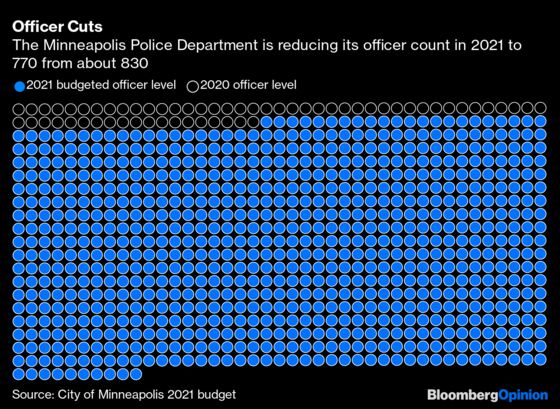

Deep attrition at the Minneapolis Police Department is compounding the crisis. Through the first quarter of 2020, more than 100 officers left the roughly 830-member Minneapolis Police Department, in addition to the 42 officers who, on average, leave every year due to age or illness. Disability claims related to post-traumatic stress following the Floyd riots account for many of the departures. Mayor Jacob Frey’s latest budget recommends a force of 771 officers in 2021, while acknowledging that the personnel cuts will “negatively impact the operations of the department by causing a significant staffing shortage and lead to increased response times” — which is already happening, according to city data. When I reached out to Minneapolis Police Chief Madeira Arradando for an interview on the topic, John Elder, a spokesperson, informed me that Arradando would be unavailable to comment because “he’s on furlough for budgetary reasons.”

City residents have noticed the impact of reduced policing. Recent polling found that 50% of Black residents oppose cutting the size of the Minneapolis police. In response to public dismay at the rise in crime, even city council members who had pledged to reduce the size of the department are now asking the department to increase its presence and response times in troubled neighborhoods, including Powderhorn.

****

For their part, the immigrant entrepreneurs on Lake Street are skeptical about the city’s ability to restore order. In recent years, many have been unsettled by President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. The coronavirus and the riots have added to their anxieties. Abdishakur Elmi, a Somali immigrant who owns the Hamdi Restaurant at Lake Street and Chicago, tells me that before the riots, his restaurant remained open until midnight. The reduction of police presence has forced him — for safety’s sake — to close at 9. Sitting in his empty dining room before lunch, he readily acknowledges that Covid has also hurt him. But then he points north, to a nearby Somali mall, and tells me that he’s heard of at least seven carjackings near it in the last week. “I don’t see police, I don’t see government agencies stopping crime. I don’t see anything.”

It’s a similar response next door, in the Midtown Global Market, formerly a Sears store, which houses dozens of immigrant-owned restaurants. Hassan Zaidi, owner with his wife of the Moroccan Flavors restaurant, tells me his income has declined 70% in 2020. Covid-19 hurt; the riots just made it worse. Zaidi, like most of Lake Street’s immigrant entrepreneurs, is careful about criticizing the authorities. After the riots, Midtown was secured by local residents and private security in the absence of police, until the National Guard showed up.

Still, like other entrepreneurs, he’s not ready to abandon the business he dreamed of starting for 30 years. “When the Floyd murder happened, we closed,” he tells me as he awaits lunch business. “Had to. But I figured out that’s not the best thing to do. What are we going to do? Get a job?” He shrugs. “The community wants to support small businesses.” When I asked him if the police were supportive, he glanced toward Lake Street. “I don't see any police. What police?”

Back at Seward Pharmacy, Elias Usso nods in the direction of the Third Precinct. Since the precinct’s destruction, the cops stationed there have been operating from a building several miles away, likely contributing to response delays. The city council recently signed off on a proposal to temporarily relocate it back into the neighborhood, but then reversed itself in the face of activist opposition.

“It’s not there,” Usso says, then pauses. “Listen, as a minority, as an immigrant, you’re concerned. What happened to George Floyd, it could happen to any Black person. Right? We’re struggling, you know, between police brutality and as a business owner, is my business safe? In between this, we got squeezed. We want fair treatment, and we want safety.”

How to maneuver out of that squeeze is the question that nags at Usso and other residents of Minneapolis. He points out the window at a group of men loitering on the street. Before the riots, he told me, that same group would congregate in front of his shop. “Homeless, some of them may have some addiction, or mental health [issues].” For a business owner, it’s a problem. “I want grandma to feel comfortable to come and get her prescription from me.”

It occurred to Usso that he could ask the police to force the men to disperse. “And then if something happened, is this business going to exist after that? That goes through your mind. You don’t want any wrong things to happen at all, the police to react unnecessarily.” Rather than involve law enforcement, he invited over a “security person,” someone who wanted to help him out, to talk to the group. These days, the loiterers hang out across the street, in front of the YWCA.

It’s a small brush stroke in the bigger, still evolving picture of what Minneapolis is going to become in the wake of the Floyd riots. A city government that signs onto activist slogans rather than doing hard policy work will simply become less relevant as residents and entrepreneurs demand seriousness and safety. In time, that leadership vacuum may trigger a law-and-order backlash that could empower the Minneapolis Police Department and make it even more difficult to push through common-sense policing reforms. In fact, some city residents quietly wonder if the police department is deliberately slow-walking law enforcement to produce such a result.

One troubling possibility is that a growing leadership vacuum, spurred by declining confidence in traditional institutions, could lead to even more chaos, as residents go beyond Usso’s gentle efforts to bring order to his own neighborhood and engage in outright vigilantism. Some residents of Minneapolis (and one Council member) have organized armed citizen patrols as replacements for the police. It’s not hard to imagine such efforts spinning out of control.

Another outcome is possible, however. Quality police reform proposals have yielded promising results in other places, including neighboring St. Paul, where youth centers, housing assistance, community-oriented policing and the widespread deployment of social workers are embraced as means to assist the police, not replace them. With a little luck, hard work and imagination, it might also bring to power a new generation of leaders who understand that community safety and justice don’t have to be at odds. They go together.

Elias Usso tells me that he’s a resident of Powderhorn, first, then a businessman, and he’s here to stay. When I ask why, he answers simply: “I believe in the neighborhood,” and gives a nod out the window to the busy traffic on Lake Street.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Adam Minter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is the author of “Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade” and "Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale."

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.