(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If Russia needed to be reminded of the costs of ignoring climate change and the transition to cleaner energy, 2020 has delivered. A devastating Arctic fuel spill appears to have been caused by melting permafrost. A heatwave has rekindled Siberian wildfires, which last year burned through 16 million hectares and choked cities. Oil, meanwhile, is still convalescing after sinking to its lowest price in more than two decades.

Unfortunately, the alarm isn’t ringing yet in the Kremlin. President Vladimir Putin, whose power base relies on hydrocarbons, has vacillated on global warming over the years. He has moved on from outright skepticism, but he remains intrigued by the potential profit from a thawing Arctic and unpersuaded by climate-change prevention measures that would carry heavy short-term costs.

The pandemic hasn’t changed things. Russia’s efforts to stimulate post-coronavirus growth are cranking up, but the country’s fiscal boost is avowedly brown, not green. It’s a choice that stores up environmental, economic and political risks for the future.

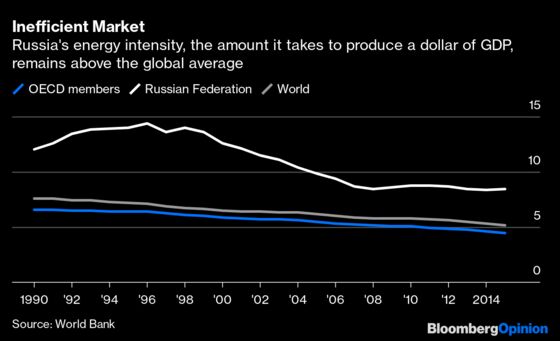

The stakes are high. Russia is the second-biggest oil exporter and the fourth-largest carbon emitter. Despite a drop in emissions since 1990, when Soviet industry crumbled, its economy still uses up a disproportionate amount of energy, more than twice the global average per person. More important, the climate crisis is having a profound domestic impact. Permafrost, the frozen layer that covers two-thirds of the country, is thawing, releasing ancient carbon into the atmosphere and threatening roads, railways and homes built on the once-solid base. On top of all this, the recent coronavirus lockdowns have given Moscow a glimpse of economic life without oil demand.

Time for a green-tinged stimulus to get the economy out of its rut? Not quite.

In fairness, other countries have a mixed approach to eco-friendly fiscal boosts. While the European Union wants to use its $825 billion Covid-19 recovery fund to foster green spending, the U.S. has extended a helping hand to its oil and coal suppliers. China — which backs international emissions goals — made supportive noises about cleaner coal in Premier Li Keqiang’s speech at the National People’s Congress last month, but there was nothing explicit on the climate.

Russia has, however, been moving more slowly than the pack. A draft low-carbon development plan published in March, the first to take a long-term view to 2050, focuses on energy efficiency without providing for a shift away from fossil fuels. It pledges to cut greenhouse gases by a third by 2030 when compared with 1990 levels, a target that still leaves room for an increase in current emissions. Targets for net-zero carbon emissions have been pushed out to the end of the century.

Domestic pressure for change is minimal. The natural resources industries have huge clout, with entire regions reliant on oil, gas and coal employment. Putin, averse to radical shifts anyway, has been left vulnerable by the Covid-19 crisis, and he’s even more unwilling than usual to risk instability, unemployment or unhappiness among the country’s resource-dependent elite. Global warming isn’t a top concern for the public either. Past climate warnings — as in 2009, when President Dmitry Medvedev spoke of the “catastrophic” threat — went unheeded.

Yet external pressures make the problem harder to ignore, as major trading partners in Europe and Asia double down on green rules, and begin to move away from dirty fuel altogether. The EU’s “Green Deal,” which seeks to hasten the continent’s transition to clean energy, is by itself a reason for Russia to develop a decarbonization strategy, says Yuriy Melnikov, senior analyst at the Skolkovo Energy Center, a think tank. Moscow must think about who the future buyers of its energy exports might be.

By passively waiting for demand signals from others, the country will only get left further behind. Climate veteran Alexey Kokorin, of WWF Russia, says it can’t sleep through this global change, then expect to run when it needs to.

Russia can weather low oil prices for a while thanks to a rainy day fund it has built for just such a purpose. But Moscow appears to believe that even if international appetite for crude oil dries up, gas exports can keep things afloat for a lot longer — especially the low-cost, lower-carbon pipeline gas offered by Russia. Rohitesh Dhawan at Eurasia Group argues that this is a miscalculation, given the plummeting cost of solar and wind.

It’s true that Russia’s domestic energy mix has a lower share of carbon than many other countries, thanks to nuclear power and hydropower, but it still depends on fossil fuels. The contribution of solar and wind energy is insignificant and it’s unlikely to breach 1% of the total by 2040, with projects treated as technological experiments, not an opportunity to upgrade an inefficient, carbon-heavy system.

As with Saudi Arabia, nobody is underestimating the challenge of making a resource-based economy more sustainable. But Russia could do more. As the painful events of 2020 unfold, Moscow has been adding to a fiscal support package. It should make it a little greener too.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.