Will China Help With Huarong’s $22 Billion Bill? Don’t Hold Your Breath

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A clumsy drama is unfolding at state-owned China Huarong Asset Management Co., the nation’s largest distressed asset manager. In January, Lai Xiaomin, who oversaw the company from 2012 until he ran into trouble in April 2018, was sentenced to death. He was found guilty of bribery, with bigamy thrown in for good measure. Lai was executed within weeks. On April 1, Huarong said it could not release last year’s financials on time. The company said the auditor needed more time and information. Caixin, an influential local financial news outlet, reported the delay was due to the possibility of a “significant” restructuring.

Huarong’s U.S. dollar-denominated bonds tumbled. The $300 million 3.375% coupon bond, due in May 2022, yielded 9.94% by Friday. With close to $22 billion dollar bonds outstanding, the quasi-sovereign issuer is now priced like China’s junk-rated real estate developers.

If anything, this bond selloff may not be enough to price in the possibility of default. A deep haircut is looming for Huarong’s gullible creditors, who had bought the bonds for its investment grade ratings. As of June, the asset manager sat on 1.6 trillion yuan of debt. Meanwhile, one-third of its 1.7 trillion yuan of assets is long overdue for deep spring cleaning: China has been trying to sell Huarong’s non-core assets for three years, with little progress.

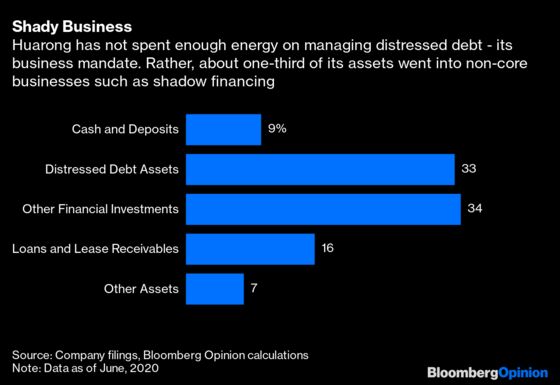

Beijing now blames Huarong’s problems on Lai who, according to Caixin, visited Hong Kong frequently and established a second family with twin children there. Instead of offloading the bad debt of China’s commercial banks — Huarong’s official mandate — Lai went rogue, dabbling in everything from private equity to junk bond trading in Hong Kong. At the end of 2016, distressed debt assets accounted for only 26% of the total, down from 34% two years earlier. Other financial investments, meanwhile, took up 40% of the total. As of June 2020, these non-core investments still amounted to 590 billion yuan, or about one-third of the total assets, data compiled by Bloomberg Opinion show.

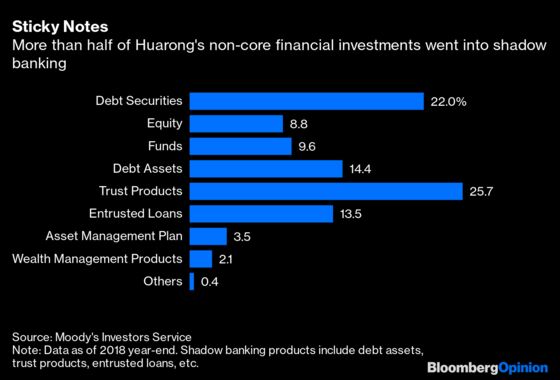

China can’t dispose of these non-core assets quickly because they are illiquid and difficult to value. If Lai had been a mere day trader, Huarong could have at least offloaded bonds and stocks via prime brokerage block trades. However, Huarong invested big time in shadow banking products via a labyrinth of joint ventures in mainland China and shell companies in Hong Kong. As of three years ago, more than half of its non-core financial investments, or 355 billion yuan, went into shadow banking, data compiled by Moody’s Investor Service show. The picture has not become any prettier. Perhaps it is time to take “a big bath,” as Caixin put it.

Optimists say Huarong will fully honor its dollar bonds. That’s because, as of June 2020, the Ministry of Finance owned 57% of Huarong. Meanwhile, dollar bond holders can take comfort that most of the notes are guaranteed by Huarong International Holdings Ltd., which according to Huarong’s latest bond prospectus, is “a core subsidiary” of its Beijing-headquartered parent.

That kind of thinking is naive. What we have here is a big tangled mess and bigamy is the perfect metaphor for looking at the situation. Like Lai, Huarong has maintained two households, onshore and offshore. But it’s become a costly arrangement and the executor of Huarong’s estate — Beijing — has to decide to support one family over the other. Which one will it be?

From Beijing’s perspective, the enthusiasm of offshore bond investors in Hong Kong was partly responsible for providing Lai with the cheap funding for his rogue ways. In 2017, Huarong International’s assets ballooned to HK$282 billion, or about 12% of the group’s total. In the ensuing two and half years, those financial assets were impaired by more than HK$12 billion; as a result, the offshore subsidiary incurred around HK$20 billion in pre-tax losses.

Huarong had no rationale for playing with the financial toys of Hong Kong when it should have been liquidating the mainland’s bad bank debt. Lai’s activities were no secret in Hong Kong’s financial circles: This columnist sounded the alarm to Bloomberg readers in August, 2017, eight months before Lai got into trouble.

Sure, it’s a big deal for an asset manager to have the Ministry of Finance as a majority stakeholder. But Tsinghua Unigroup Co. Ltd. and Peking University Founder Group were also ultimately state-owned (in their cases, control is traceable to the Ministry of Education). Yet China allowed the commercial branches of its two most prestigious universities — one of which is President Xi Jinping’s alma mater — to default. If he wouldn’t intervene on his old school’s behalf, Xi is unlikely to fill in deficits left by a rogue executive.

Indeed, China’s government doesn’t legally have to do anything: Huarong’s dollar bonds are guaranteed by the offshore subsidiary — not by the parent company. On its own, Huarong International will have trouble honoring all the outstanding dollar bonds. It held only HK$16.9 billion of cash as of June. Half of its HK$198 billion of assets are loans to “fellow subsidiaries,” which may take a long time to convert to cash; another 20% are financial assets, which are prone to impairments.

Huarong’s parent company may have provided the so-called keepwell deeds for most of these bonds, but those are nothing more than gentlemen’s agreements. What the Chinese courts’ stance on keepwells is anyone’s guess — there have been too few bankruptcies to establish any kind of precedent.

So expect a restructuring. And this is what it will probably look like: Huarong’s core business — disposing of distressed assets — will survive because China has $2.7 trillion yuan of non-performing loans that need to be packaged off. But the same can’t be said of the dollar bonds. China’s ire over Huarong’s irresponsible pile of non-core assets hasn’t been assuaged by Lai’s execution. Everyone who enabled that behavior will have to suffer a severe haircut.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.