How Old-School Connections Are Changing the Auto Industry

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The world’s largest automaker has some lessons for its peers reveling in their pandemic-time earnings bump: For lasting results, it’ll take more than just selling a large number of cars at high prices.

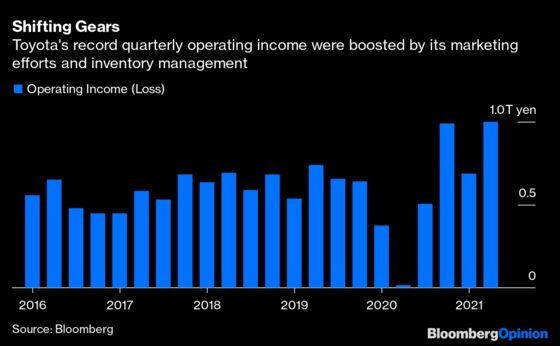

Toyota Motor Corp. had a record quarter, posting operating income of 997.4 billion yen ($9 billion) for the three months ended June. Since every carmaker is delivering stellar results so far this year — despite spending the last several months whining about chip shortages and raw material costs — that’s not much of an anomaly. It’s how the Japanese behemoth achieved this that stands out.

The company effectively turned the screws on its distribution model — a key part of the automotive industry that doesn’t get as much attention as the manufacturing part. Recognizing that it needed to do more to manage finished products and get them to the right places, including distribution hubs, dealerships and ultimately, customers — and not just worry about making cars — has put Toyota ahead of its peers.

As Covid-19 and other supply chain blockages interrupted production, automakers turned to quick solutions to leverage the building demand. They sold cars without certain chips and made more of the higher-price sport utility vehicles, helping boost their margins. Toyota did this — and more: It focused on how cars were sold to customers.

Car companies usually don’t do that. They fill factories and produce as much as they can based on past customer data to come up with forecasts that allow them to cover high fixed costs. Then, they ship the vehicles off to their dealerships that sit on the inventory and sell to customers.

Even though this strategy isn’t the most efficient and comes with high costs, pushing supply out works in normal times. But in the middle of a pandemic, it’s hard to gauge demand accurately, or know what customers want to buy and how to get it to them. That’s been even tougher with supply chain disruptions that have caused shortages, shuttered production facilities and pushed up raw material prices. In times like these, automakers can’t just churn out cars and hope to sell them.

Recognizing this friction, and that it was here for a while, Toyota leveraged its old-school model rooted in deep relationships and networks. It worked with its regional distributors to gauge demand for the type of cars they needed and a clear picture of its pipeline of vehicles — whether they were in manufacturing plants, on freight carriers, in transit, or at other dealerships. This allowed it to manage inventory across every layer of its manufacturing and sales operations, bringing down the average number days it takes the company to turn stock into sales.

Further down the chain, it worked with dealerships to get them the right numbers and models. The company also allows dealers to trade or transfer cars, making it faster to get them to buyers. The biggest boost to its operating income came from what the company calls its “marketing efforts.” Simply put, that’s a combination of sales volumes, the mix of vehicle models, prices and incentives. Working with its dealerships through its distribution centers and factories, it finely calibrated sales and the types of cars it sold to manage demand and supply.

Even with their plump margins, carmakers are beginning to see they need to do a better job managing the imbalance between the high demand for cars and limited supply. Even the likes of Carlos Tavares, CEO of Stellantis NV, the auto giant formed through the merger between Fiat Chrysler and PSA Group, are now talking about how to sell cars. On an earnings call this month, Tavares said as the firm’s order book grows and its dealers adapt to a “new reality” of the pandemic and a move toward greener cars, they’re now discussing “different ways of retailing the products, maybe a different distribution model.”

Whether post-Covid 19 sales and demand continue at the current pace is still hard to say. But one thing is clear: If global automakers want to stay ahead and post the results that the pandemic has surprised them with, it’s time to think about how they can sell cars more efficiently.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.