How to Price in Rent Inflation and Russia Tensions

(Bloomberg Opinion) --

The next episodes of the great inflation running story are already set. Jerome Powell will testify to the Senate at his reconfirmation hearing Tuesday, followed Wednesday by the release of the final inflation numbers of 2021, the year when rising prices made a sudden and widely unexpected return. But for the rest of 2022, the drama could be centered on landlords, tenants, and the markets that finance them.

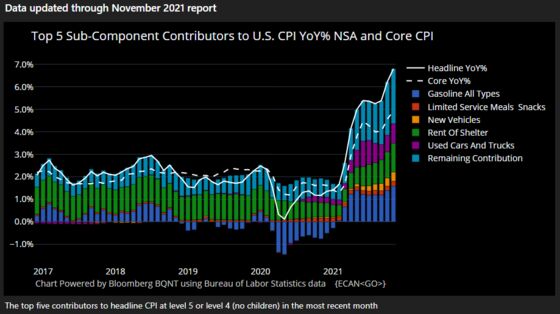

Rents make up the single biggest portion of the consumer price index. By November, they were contributing more than any other single category to the overall number, except gasoline. This chart was produced by the ECAN service, which is available on the Bloomberg terminal:

The growing contribution of rents, in green, to inflation was due to dynamics following the pandemic, which saw rents fall, and then rebound to their highest rate of increase since 2007:

While it has risen sharply, rental inflation remains within its long-term range. However, there is very good reason to expect rents to rise further. The housing sector has boomed since the worst of the pandemic shutdown early in 2020. As one good indicator of this, the Hoya Capital Housing 100 index, which covers a range of stocks that benefit most from a shortage of accommodation and an active housing market, has slightly outpaced even the mighty NYSE Fang+ index since the nadir of March 2020. There is intense activity in the sector:

Meanwhile, the mechanics of the way the official CPI data are collected gives us great leading indicators on where rental inflation is heading. The CPI captures the average being paid in rent, including people from the first through to the last months of their lease. Several different services monitor the rents on new leases. Zillow’s index suggests that rents rose more than 10% last year, and the official data can be expected to catch up. Meanwhile, census data shows vacancies dropping to historic lows, implying that the upward pressure should continue. The official rental inflation measure is much criticized. David Wilcox of Bloomberg Economics explains why the CPI seems so far behind:

- The CPI aims to measure rents on all units, newly occupied or not. The latest twitch in the management company’s front office may not be relevant for the bulk of renters until many months later, when their leases turn over.

- For technical reasons, the CPI builds in six more months of inertia. Eventually, it catches up to reality on the ground. Most of the time, when rents are moving slowly the additional inertia isn’t an issue, but now is not normal.

On the face of it, higher inflation of rents in 2022 is a very safe bet. Wilcox suggests that 6% or 7% is likely by year-end, which would be the highest level in three decades:

For those hoping to avoid sharp rises in target interest rates, this is bad news. There are serious arguments over whether tighter monetary policy can help control price increases driven by supply chain disruptions. But when it comes to the housing market, the relevance of a tougher Fed is obvious. Most transactions there rely on mortgage finance. Pushing up bond yields raises mortgage rates and should help bring house prices and rents under control, with a lag. Benchmark Fannie Mae mortgage rates have risen significantly in the last few weeks, but still remain far below even their level from the top of the last housing bubble in 2006. Further increases in shelter inflation would make it very hard for the Fed not to become much more hawkish.

Markets in both stocks and bonds sold off and then regained more or less all of their losses during Monday trading, in reaction to news items on the Fed. Jerome Powell, we now know, will say it’s his mission to make sure inflation doesn’t “take root” in the U.S. economy. Bill Dudley, the former head of the New York Fed, writes for Bloomberg Opinion that the central bank should be “a lot more hawkish.” All of these things matter. But the housing market could yet be crucial. If rental inflation takes off, as it seems reasonable to fear, the Fed will have no choice but to get a lot more hawkish.

From Russia With Love

One thing seems rather strange about the market focus on rates and monetary policy at present. It’s happening as the U.S. and Russia, which spent 45 years not-quite-fighting each other in the Cold War, meet for a conference that is trying to avert a Russian invasion of Ukraine. If that happened, it would be the first invasion of one sovereign nation by another in Europe since the end of World War II. The amount of Russian military hardware massed near the border suggests that Moscow wants the threat to be taken very seriously. And its control over supplies of fossil fuels brings power over U.S. allies in the European Union.

Put like this, it sounds like potentially the biggest shock to the world political and economic order in decades. Yet the market fallout is not great thus far, and confined almost entirely to Russian assets. The RTS index, the most widely cited Russian stock index, has dropped nearly 20% since a top last month. Russian stocks usually follow oil prices, but their recent revival hasn’t helped — so investors do see this as a serious issue for the country. But such a situation might be expected to send investors rushing for the shelter of U.S. Treasuries. As we know, the exact opposite has happened. The elevated international tension has also had little impact on U.S. stocks, which set highs last month even as the Ukrainian situation was worsening:

Why so calm? Investors think, surely correctly, that the chance of direct armed conflict between the U.S. and Russia is roughly zero. It isn’t going to happen. If President Vladimir Putin does invade, the chances of significant economic damage also seem limited — he won’t unless confident of emerging relatively unscathed. That in itself makes an armed invasion unlikely. The power politics of the situation are fascinating, but in financial terms the possibility of inflation and higher rates in the wake of the money that got us through the pandemic dwarfs them.

However, that doesn’t mean that the talks over Ukraine can safely be ignored. The danger that prompted investors to sell Russian stocks is that the U.S. would hit them with serious economic sanctions, like those against Iran. Russia could be excluded from the SWIFT international payments system, and global buyers could be blocked from Russian debt. This is a credible threat, and would hurt Russia’s economy a lot. The questions that need to be considered more carefully are what the implications would be for the rest of the world’s economy, and what possible “upside” the talks might produce.

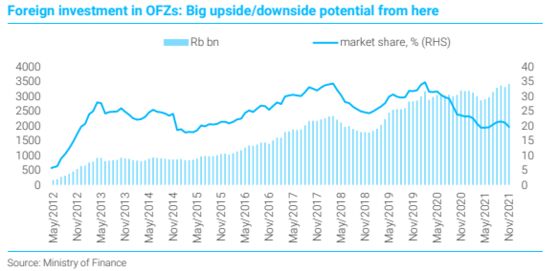

Christopher Granville of TS Lombard offers this chart to show that foreign investment in Russian debt has been rising, even after the first crisis over Ukraine in 2014. A buyers’ strike would be very damaging, with little obvious collateral damage for other economies. It wouldn’t be difficult to reallocate funds elsewhere:

But there would be more collateral damage. Cutting off trade with Russia means voluntarily severing access to a huge supplier of oil, natural gas, and many industrially important commodities. Prices would rise, and the effect on inflation, the great concern of the moment, would be great. It isn’t unthinkable, and the U.S. will try very hard to avoid such an outcome. This downside does not, as yet, appear to be in market prices.

That creates the chance of an upside for Russia, and arguably everyone else, in which the country gains some guarantees that NATO will not station forces close to its borders or will not expand, in return for a commitment by Russia not to station its forces close to Ukraine’s border. That would result in a significant reduction in perceived global risk and probably help commodity prices to fall.

This then becomes one of those difficult situations where the outcomes are not strictly binary, and include realistic possibilities of both negative and positive results. And perversely, as the U.S. has made it clear that it will not be involving itself militarily, it is harder to ignore. Risks of an asteroid destroying the planet, or of a nuclear holocaust, are so unthinkable that there is no point in financial markets trying to take account of them. As Granville points out, that isn’t true of the Ukraine standoff:

However remote the possibility not only of Russia invading Ukraine but also, in that event, of the US going all the way with such a ‘nuclear’ sanctions response, such risks can and will be priced in by markets. Here lies a key contrast with other geopolitical flashpoints like North Korea or Taiwan, where the risks are more of the end-of-the-word-as-we-know-it kind that markets cannot, and therefore do not, discount. For unlike the spectre of great-power and/or nuclear conflict in east Asia, the Biden administration is ruling out a direct clash between nuclear-armed powers in Ukraine. Any conflict in Ukraine would thus remain regional rather than of the all-bets-off variety – meaning that markets would bet on the consequences, transmitted through commodity prices in the first instance but with potentially strong negative spillovers into rates and earnings expectations

Attention will doubtless focus on the Federal Reserve and the congressional hearings. Ukraine has the potential to make a very big impact of its own before the week is out.

Survival Tips

Let me offer something classical for a change. It appears that Schubert's Ninth “Great” Symphony is lapsing from the public memory. While back in the U.K., I watched University Challenge, a quiz show for students that many years ago gave me one of my life triumphs, and is something of a British institution. When played a passage from Schubert’s Ninth, however, none of this year's entrants could recognize it. It’s one of the greatest of masterworks, containing immense variety, and scarcely ever giving away that it was written by a man who had only just turned 30 and was dying of syphilis. If you need something to lose yourself in for an hour, try listening to it.

More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

- The Federal Reserve Needs to Get a Lot More Hawkish: Bill Dudley

- Fed Forced to Run Triple Option With Time Running Out: Mohamed El-Erian

- Mild Omicron and an Aggressive Fed May Hurt Gold: Liam Denning

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.