(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This is one of a series of interviews by Bloomberg Opinion columnists on how to solve the world’s most pressing policy challenges. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Robert A. George: The spiraling cost of higher education in the U.S. has become a source of growing anger among students, parents and policy makers and raised questions about whether college remains an engine of economic opportunity. You’re the president of St. John’s College, which is unique for adhering to a Great Books curriculum and for having two campuses, one in Annapolis, MD and another in Santa Fe, NM. (Full disclosure: I’m a 1986 graduate of St. John’s.) You’ve also done something else that’s nearly unheard-of for small liberal-arts colleges: you slashed the cost of tuition. Can you talk about that decision?

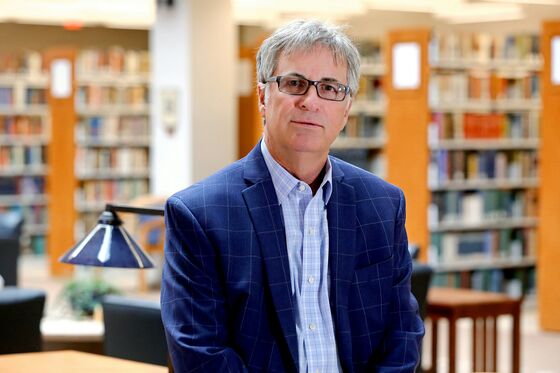

Mark Roosevelt, president, St. John’s College: St. John’s, as you well know, Robert, prides itself on being different. We’ve not succumbed to what many of us think are probably ill-advised trends in American higher education — such as, for example, allowing students pretty much to design their own curriculum and take what they want in college. We’re proud of being called the most contrarian college in the country. But one of the trends we did succumb to was a ridiculous escalation in the price of college, which in recent years tripled or quadrupled at the rate of inflation. It was costing over $60,000 a year to attend St. John’s. We believed that many people who may have sought what is on offer at St. John’s might have been turned away immediately by just looking at that sticker price.

College financing is a game — because nobody, or hardly anybody, pays the full price. But not everybody knows that or knows how to go about the negotiation of that. So we recommended lowering tuition to $35,000, which is still obviously a significant amount of money, probably about the average net annual income in New Mexico, where I live. We’re not being “high horsey” about this. We did allow our tuition to get way too high and so we brought it back. So now it is lower than it was 12 years ago. We would love to hold this number. We certainly don’t want tuition going forward more than the rate of inflation.

RAG: How was this recommendation to cut tuition by basically one-third received by the board of trustees? What was the plan to cover such a reduction?

MR: There was a revenue loss, but not a significant one. The ambition was that the average student at St. John’s would pay about $21,000. We wanted to have more students paying in that middle range. And it worked. Our actual net tuition revenue went slightly up. That’s counterintuitive, but it did. It took a while for the board to wrestle with this, but ultimately, we made the decision in an eight-month timeframe. We had also surveyed our alumni community: many had expressed rather deep displeasure at how expensive the college had become and feared that they wouldn’t be able to afford to send their own children there. We asked our alumni, “How would you feel if the college took an act like lowering our tuition significantly?” We received nearly unanimous positive reaction to that. So we felt confident that the tuition cut would boost the capital campaign, it would inspire donors to dig deeper, and it offered us a way of also being more honest.

RAG: Both of your campuses are rather small – around 400 students on each. Have you noticed more interest in St. John’s because of the tuition cut?

MR: We can’t tie it directly. But yes, we’ve had a record number of applications. We don’t usually get that many applications. People don’t apply to St. John’s who aren’t serious about it. Even so, we are up about 10-15%. If you count the graduate programs over both campuses, there are about 1,000 students. It’s very healthy for the college to be full; it feels better, it’s financially better, it’s atmospherically better for the students. I think we’re also doing a better job of getting the word out in good places about what it is that we do and the kind of students for whom that works.

RAG: The faculty and class structure of St. John’s are unique: students take tutorials, seminars and labs and instructors are “tutors” instead of professors.

MR: Yes. We have no lectures, no adjunct faculty. When it comes to liberal arts colleges, we’re as different from Middlebury and Oberlin and Pomona as they are from Ohio State. There are many forms of quality education in America, thankfully, and this is one. I don’t mean to say ours is superior to others. It’s just damn different and more demanding. We don’t believe that knowledge is divided by departments. Faculty teach across the curriculum. And in addition to the “Great Books,” as you said, we also demand high-level math and high-level science. It’s designed to try to create a platform of knowledge to begin a life of learning. If you have a platform in which to operate, that means you’ve got to know a lot of things across a very wide variety of subjects.

RAG: Nonetheless, St. John’s faces the same real-world challenges as its peers. There’s a lot of examination about not just the basic cost of college, but the return on investment. Whether it's $50,000 or $35,000 to $25,000, a year in tuition, is it all worth it? You may have a student interested in the college and the parents ask the classic question, “What are you going to do after you get out? Are you gonna make enough money?”

MR: It’s a very legitimate conversation. We would make the argument that a college education indeed does prepare you for a career and for better economic circumstances, but we would like to make an additional argument as well — which is that it prepares you for a different kind of life, a richer life, using that word in its multiple meanings. Of course, being able to put food on the table and a roof over your head is essential to a good life. But contemplating questions like, Why are we here? What are we doing? How should we spend our lives? These also contribute to a life and I think we do a very nice job at St. John’s of helping students ask those basic questions and begin to develop a personal philosophy that will help them at all stages of their lives.

RAG: Over the last year and a half, there’s been a society-wide conversation around issues of equity and inclusiveness. A lot of the focus has been on race and ethnicity, but it involves class as well. Recently, Amherst decided to end legacy admissions. Is this something that higher education – liberal arts schools in particular — should be more sensitive to? More broadly, how should schools balance issues of equity and excellence?

MR: Let me take the second question first.

St. John’s prides itself on taking a lot of students for whom high school was not a good experience. They just didn’t fit in. They have the acumen and the wherewithal to do high-level academic work, but they haven’t necessarily shown it in a way that would get them considered by an Amherst. That said, we have done a lot in the last few years to provide more academic supports for those who didn’t have a rigorous high school education that prepared them particularly well. We now have a summer bridge program – a couple of weeks in which we invite prospective students to come to learn what is expected at St. John’s, to get some idea about how a seminar is run or be told about study habits that will serve them well. Getting behind can be very bad, because it’s hard to catch up.

One of the transitions from high school to college is learning how to work independently. You have to learn how to do the work on your own, without somebody watching over you. Most schools have these programs. And they’re not just for poor kids or for kids who went to, you know, less fine high schools, but they’re for anyone who thinks it will be beneficial. Students here take Greek as freshmen, for instance, and a lot of students struggle with Greek.

RAG: I can personally attest to that.

MR: Yes. This is because we want to keep the academic program rigorous. And to me, the more rigorous one’s program, the more robust support should be. If you intend to keep it rigorous, then provide the supports. Don’t dumb it down. Nobody here wants to do that. We do want to make sure that students have the opportunity to make it through, because everybody struggles and everybody needs help at one time or another. So we’ve really increased those supports.

To the larger question: yes, I’m convinced that the prestigious schools in this country – schools like Harvard, Princeton, the other Ivy League schools, the Amhersts, the Williamses — have not done as much as they can to be effective up-escalators for people. They can pridefully tout their numbers of kids on scholarship and all that, but the numbers are still clear that in the main, their larger service is to people who already come from tremendous advantage. I would never tell anybody else what to do. I don’t consider myself smart enough or knowledgeable enough to do so. But the numbers do bear out that higher education as a whole is more a contributor to inequality than an answer to inequality and that’s too bad. So what Amherst and other places are thinking about is very justified and warranted.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert A. George writes editorials on education and other policy issues for Bloomberg Opinion. He was previously a member of the editorial boards of the New York Daily News and New York Post.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.