(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A booming stock market at a time of pandemic recession and widening inequality is an unfortunate combination, so the tax raid on the Hong Kong exchange shouldn't be a surprise. Soaking well-to-do finance types to help pay for consumption handouts sends a convenient populist message. It may also serve to deflect attention from the government’s failure to tackle the biggest contributor to the city’s wealth gap: property.

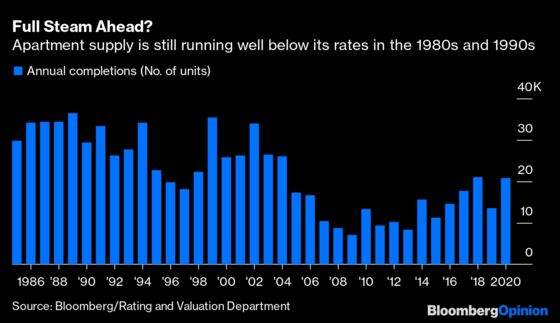

Annual home supply in the coming five years is expected to be 38,280 units, based on figures in last week’s budget, falling 11% short of the government’s target of 43,000, according to Bloomberg Intelligence’s Patrick Wong. Public housing supply will be 33% below an annual goal of 30,100. By contrast, regional rival Singapore, which runs a comprehensive public housing program, has a glut of apartments. A year ago, Hong Kong Financial Secretary Paul Chan said the government was pressing “full steam” ahead with the recommendations of a task force set up to examine inadequate land supply, though that line didn’t feature in the 2021 presentation. The government will sell 15 residential sites in the coming year, capable of providing a mere 6,000 homes.

Hong Kong has a housing crisis. As of 2016, the city of 7.5 million had an estimated 210,000 people living in subdivided apartments, tiny spaces carved out of existing dwellings where low-income residents pay exorbitant rents, often in older, crumbling buildings that have exceeded their serviceable life. The partitioning is frequently illegal, with electrical rewiring and plumbing alterations that create fire and health hazards. The proliferation of these invisible slums is a product of insufficient home building, itself the legacy of historic mistakes in public policy.

On the face of it, the government’s reluctance to accelerate housing production more aggressively might seem puzzling. During the 2019 pro-democracy protests, China’s state media frequently linked Hong Kong’s social discontent to livelihood issues such as the housing shortage (though there was little evidence of this). With mainland officials now taking a more direct hand in the city’s affairs, one might expect them to move with alacrity to address the problem.

That they are not shows just how intractable the challenge has become. In the government’s telling, supply is a matter of physical constraints: Hong Kong is simply short of land, and this dearth cannot be solved quickly or easily, a narrative that helps to support its case for building 1,000 hectares of environmentally destructive artificial islands in the waters west of Hong Kong island. Besides costing $80 billion, this project will take decades to come to fruition.

Some are dubious, pointing to a wealth of alternative land sources, from brownfield sites to the untapped potential for regeneration of a decaying urban housing stock. Private developers have vast agricultural land banks in the New Territories that they could be compelled to put to use. In reality, the more significant impediments to a radical upward shift in home supply are market, economic and political.

In 1997, Hong Kong’s first post-colonial chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa, adopted an ambitious target of building 85,000 apartments a year. Almost immediately, the city was engulfed by the Asian financial crisis and property prices plunged. Tung’s housing policy helped to spook the market and was quietly dropped. The government stopped selling land and dismantled its highly successful public housing program, liquidating its land bank, as the late Leo Goodstadt, an academic and adviser to the pre-handover government, recounted in his 2018 book, A City Mismanaged: Hong Kong’s Struggle for Survival.

That left authorities unable to respond when property prices started to recover. Developers, alert to the dynamics of recovering demand and a paucity of supply, withheld completed apartments from sale and waited for prices to rise further. The housing sector has never recovered. In the 15 years through 2000, annual supply averaged more than 30,000 homes. In the past decade, it has been less than half of that.

Having plunged almost 70% by their 2003 nadir, home prices rose sixfold over the following 16 years, reaching a record in mid-2019. For 11 years, the city has been ranked as the world’s most unaffordable residential market.

This is the Gordian knot the Hong Kong government faces. With the property market perched at such precariously high levels, and the memory of Tung’s 85,000-a-year target etched on the minds of officials, any fundamental change in supply would risk a disorderly and painful adjustment. That would distress and alienate the city’s homeowning middle classes — the last thing Beijing needs, having already made enemies of the unpropertied and disaffected younger generation. There’s also the possibility of a demand shock, with hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong citizens forecast to emigrate to the U.K. following the passage of a national security law last year.

A renewed slump in housing values would also undermine public finances, with the government overly dependent on “land premiums” — the taxes that property companies pay for the right to develop. With Hong Kong facing a record budget deficit, that prospect is unthinkable. Stability will trump all.

The conclusion for homeowners and potential investors in Hong Kong property should be comforting: Supply will remain tight, as protecting the market takes precedence. For the city’s most disadvantaged, the outlook is less cheerful. Hong Kong’s subdivided apartments are a badge of shame for such a wealthy city, particularly when set beside Singapore’s world-class public housing. They’re going to be around for a while longer.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matthew Brooker is an editor with Bloomberg Opinion. He previously was a columnist, editor and bureau chief for Bloomberg News. Before joining Bloomberg, he worked for the South China Morning Post. He is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.