(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s going to be a good summer for corn farmers. Speculators best hope it’s a very dry one, too.

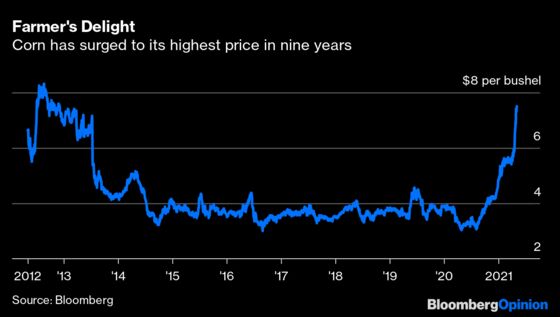

Having scraped $7.50 a bushel, corn is up roughly 50% so far this year, hitting its highest level since 2012. Like all commodities, it’s feeling the recovery from Covid-19, including big post-pandemic restocking by China. A rebound in gasoline demand, with its attendant corn-based ethanol component, helps too. The essential element is on the supply side, however, with drought, both actual and feared, providing an extra boost.

Feverish talk of a new commodities supercycle has also been thrown around in 2021. Yet the premise is flawed, and grains certainly won’t drive one.

Unlike metals or fuels, spikes in crop prices tend to be short-lived. Shortages induced by weather such as droughts or floods are usually brief and isolated in their impact. And while bringing a new mine or oilfield into production can take years, farmers respond to price signals on a seasonal schedule.

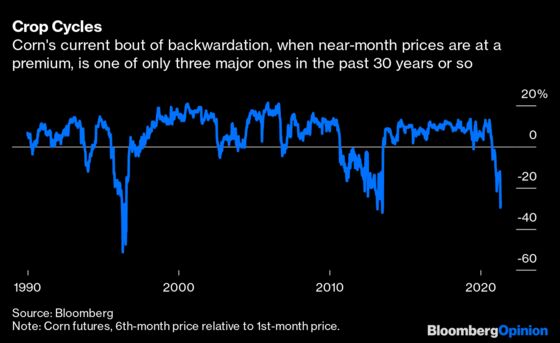

And they certainly have a signal. Time spreads — the difference between the first and sixth futures prices — have widened sharply. The discount on the sixth-month contract is the deepest since 2013 and one of only three such periods of steep backwardation since 1990.

In 1996, when backwardation in corn was the steepest of the past three decades, front-month futures prices dropped by a third within six months of hitting their peak. The episode of the early 2010s lasted longer, with a double price peak in 2011 and 2012 as persistent drought tightened supply. Still, if you bought at the second peak, you were down by a third within two months or so.

Speculation in corn has also amped up, with the ratio of long-to-short money among hedge funds around 14 times versus a five-year average of about two times. Similar variance can be found across a range of grains and soft commodities like sugar and cotton.

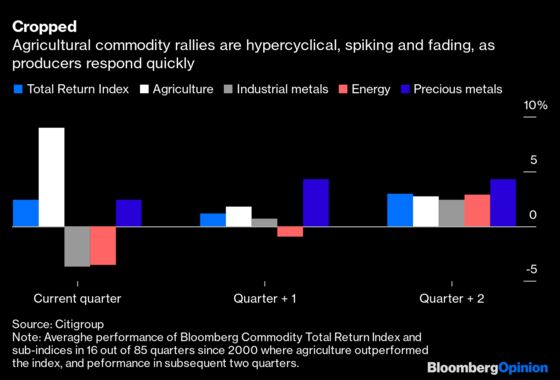

Money chasing momentum doesn’t guarantee an imminent crash, of course. And an intense drought or some other factor could mean an extended rally similar to a decade ago. But it does mean that if the weather gods don’t deliver, there’s an overhang liable to collapse quickly and messily. A recent analysis by Citigroup looking back to 2000 found that while outperformance in agricultural commodities can be dramatic, it’s also usually quite fleeting.

Another commodity that owes quite a bit to American farmland has experienced a similar dynamic lately: oil. A characteristic of the shale boom was the compression of production schedules from years to months for that small but influential part of global supply. Similar to farmers, rising prices let frackers lock in cash flow by selling futures, leading to a supply response relatively quickly.

More than anything, that interplay of U.S. capital markets with shortened production schedules played havoc with OPEC’s attempts to manage prices this past decade. It also means that with longer-dated futures prices now firmly above $60 a barrel, the newfound discipline of shale producers could start to crack and generate a response in the form of higher production next year. Similar to corn, this would act as a natural cap on rallies.

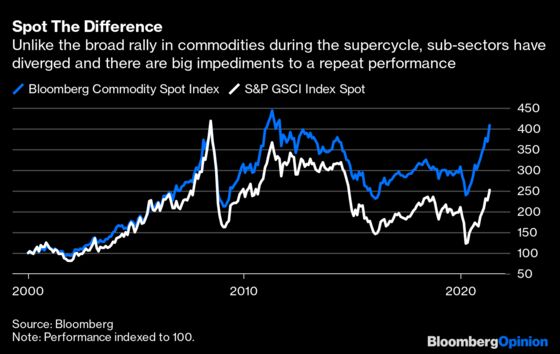

This brings us back to the revived supercycle thesis. Unlike the last one, there are big impediments to a broad rally in commodities. Agricultural rallies tend to fade quickly. Energy has a structural issue in the form of spare OPEC+ supply capacity, meaning there’s enough physical oil to absorb higher demand.

Gathering efforts to combat climate change are a structural impediment on the demand side (which will also limit ethanol; sorry, Iowa). Industrial metals, on the other hand, look better positioned for a world that is rebuilding and electrifying.

Overall, though, there’s a reason why the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index is at its highest level in a decade, while the more energy-weighted S&P GSCI index is only back to where it was in 2014, when oil’s supercycle crashed.

Corn’s moment in the sun will need a lot more sun to keep going. Even then, a shift in the market’s weather is inevitable.

"Corn Rally at Risk of Being Cured by High Prices", Bloomberg Intelligence, April 16, 2021.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.