Higher Prices Are Here, Whether or Not You Call It Inflation

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Here are the most important questions about the current inflation wave:

- Are lots of things more expensive than they used to be (and are they going to stay that way)?

- Will prices keep rising over the next few years?

The second question has been the subject of a seemingly unending stream of analysis and debate this year. Prices of financial assets depend a lot on expectations of future inflation, so it’s understandably of great interest to investors. Keeping inflation from spiraling out of control is a key job of central banks, so it’s also of interest to central bankers, the economists who wish to influence them and the investors who watch their every move. The business and financial media cater to these people and rely on them as sources, so this is the question that dominates our coverage too.

It’s a not-unimportant question for people outside these circles too. Your opinion on whether, say, car prices will keep rising over the next few years will shape your near-term buying and selling decisions. Still, my impression is that potential future inflation is much less important to most of us in our daily lives than the fact of higher prices now. Things cost more, which is tough for many people. And while this is getting some attention in the media, it’s far less than what’s being devoted to the question of whether inflation will be high in the future.

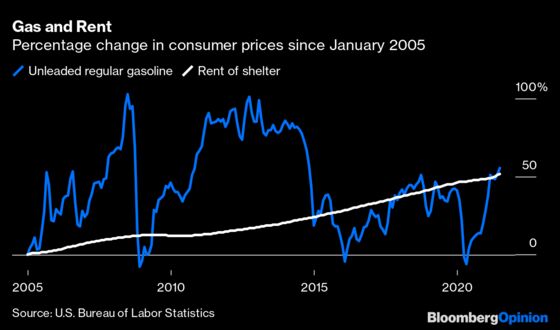

So let’s give it some attention! The answer to the question of whether prices are higher is, of course, yes — 5.4% higher than a year ago, as of July — and the answer to whether they will stay that high is almost certainly also yes. There are some consumer items, mostly commodity-based, that will on occasion go down in price by as much as they’ve risen. But most of the things we spend our money on don’t do that. As an illustration, here’s how the consumer price indexes for gasoline and rent have moved since 2005.

It’s this volatility of energy prices that causes monetary policy-makers to focus on measures of core inflation that exclude energy and food. The reasoning is that core inflation is a better indication of the inflationary trend, and thus a better predictor of future inflation. Which makes sense, although it understandably irks people during periods of rising energy and/or food prices that policy-makers choose to focus on the core instead.

Right now, headline inflation and core inflation aren’t that far apart, with the Consumer Price Index excluding food and energy up 4.3% year-over-year. True, nearly a third of that (if I’ve done my calculations correctly) was due to the skyrocketing price of used cars, which have experienced some pretty unique supply-and-demand dynamics over the past year. Their prices barely budged from June to July and will probably subside somewhat in coming months, as may some other “core” inflation components that have been affected by pandemic supply-chain issues.

“As supply problems have begun to resolve, inflation in durable goods other than autos has now slowed and may be starting to fall,” Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell said in his big Jackson Hole speech on Friday. “It seems unlikely that durables inflation will continue to contribute importantly over time to overall inflation.” He also noted that durables prices had declined in recent decades. He did not, however, say he expected prices to revert to what they were before the pandemic.

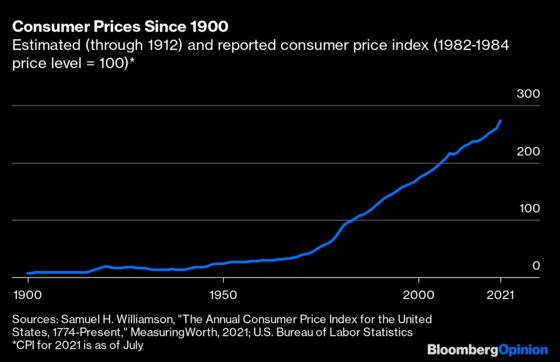

This actually used to happen. There were several big inflationary episodes in the U.S. before the 20th century, but prices fell afterwards and the overall U.S. price level in 1900 was about the same as in 1776.

In 1913 Congress created the Federal Reserve system. Since then there have been two major deflations, in 1921 and in the early 1930s, but neither brought the consumer price index back down to the 1900 level. The Great Depression did bring prices back down to where they’d been in 1917, and the consequences for an industrial economy with lots of business and consumer debt turned out to be pretty awful, as economist Irving Fisher explained in his influential 1933 article, “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions.” Ever since, central bankers have been doing what they can to avoid significant deflation.

The bargain the central bankers have struck seems reasonable enough, as long as they don’t make too many mistakes like in the 1970s when inflation got truly out of hand. But it means that most of this year’s price increases are likely to stick. Incomes are going up too, with employers boosting wages to fill a record 10.1 million job openings and next year’s Social Security payments likely to include a cost-of-living adjustment of more than 6%. In the short term consumers are able to buy less, though, and too much of an upward income adjustment risks creating a spiral in which price increases continue into the future.

The current consensus of the many smart people debating and analyzing these matters seems to be that the spiral won’t develop and inflation will settle down soon. I think that’s probably right, although I wouldn’t be too confident about it given that the consensus generally underestimated how bad inflation would get this year. While we’re waiting to find out what inflation does in the future, though, it is undeniable that things cost more now, and that’s no fun.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.