If Hedge Funds Are Lagging, Why Do They Have So Much Money?

In many important ways, equity hedge funds have actually been less stable than the market since the financial crisis.

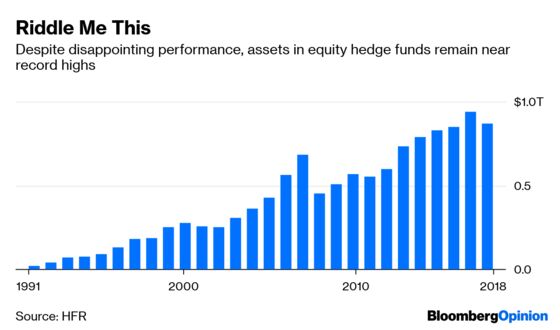

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- By now it’s no secret that equity hedge funds have had a horrible decade. The real surprise is that a record $955 billion was invested in those funds at the end of September 2018.

Which raises the obvious question: Why are so many investors still hanging around?

During the go-go 1990s and the boom years between the dot-com and housing bubbles in the 2000s, the pitch for hedge funds was simple and sexy: “Give us your money and we’ll make you rich!” Sure, the fees were absurdly high, but investors weren’t as fee conscious then as they are now, and in any event, they were making too much money to care.

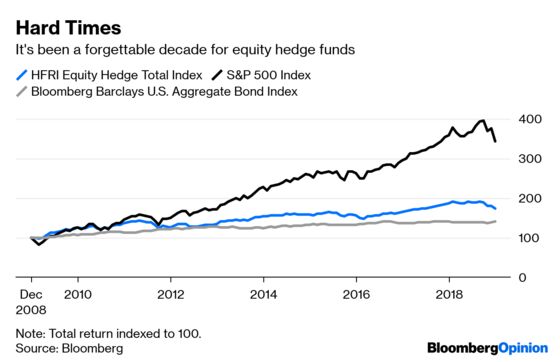

Managers had good reason to be confident. In 1990, there was a scant $14 billion invested in equity hedge funds, so there were more opportunities for outsized returns than money chasing them. Hedge funds took full advantage, and the HFRI Equity Hedge Total Index returned 16.6 percent a year from 1991 to 2007, outpacing the S&P 500 Index by 5.2 percentage points, including dividends.

Investors piled in along the way, and by the end of 2007, assets in the strategy ballooned to $685 billion, far more than equity hedge funds could realistically manage if they wanted to continue outpacing the market. The 2008 financial crisis didn’t help, either. It whipsawed hedge funds, as it did many other investments, and managers struggled to regain their golden touch. But they weren’t keen on returning the money to investors and giving up their lucrative fees, so they did the next best thing: They pivoted from making money to not losing it.

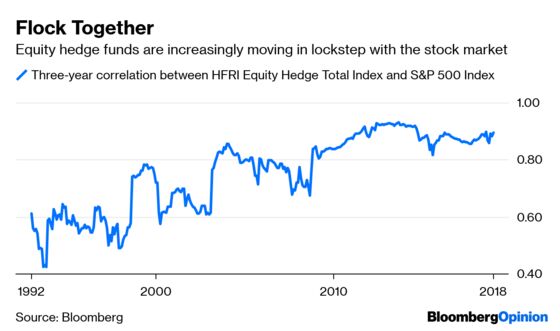

The new objective, they argued, was to manage risk by protecting investors during downturns and delivering returns that are uncorrelated with the stock market. Sure, they may lag the market, they conceded, but it’s better than bonds, particularly with interest rates at historic lows in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

It’s hard to imagine a lower bar, and incredibly, hedge funds failed to clear it. In many important ways, equity hedge funds have actually been less stable than the market since the financial crisis. The equity hedge index has posted a negative one-year return 26 times since 2010, based on monthly returns, with an average decline of 4.4 percent. By comparison, the S&P 500 was down just five times over one-year periods, with an average decline of 2.5 percent. And last year, perhaps the most turbulent one since the financial crisis, the equity hedge index was down 7 percent, compared with a decline of 4.4 percent for the S&P 500.

Also, the correlation between equity hedge funds and the market was higher during the last 10 years than previously. The average three-year correlation between the equity hedge index and the S&P 500 was 0.68 from 1992 to 2007, the earliest period for which numbers are available. But that correlation climbed to an average of 0.88 since 2008, a near perfect correlation.

Meanwhile, bonds proved harder to beat than hedge funds anticipated. Yes, the equity hedge index outpaced the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index by 2.2 percentage points a year from 2009 to 2018. But on a risk-adjusted basis, a measure closely watched by hedgies, bonds won easily.

Which brings us back to that record $955 billion.

I have two guesses as to why investors have stuck around. The first is that institutional investors, which account for most of the money invested in hedge funds, have succumbed to inertia. Institutional money is generally overseen by investment committees. Those committees are famously risk averse and slow to act, which has made them ideal targets for hedge funds in recent years. That purported pivot to risk management had to be particularly enticing.

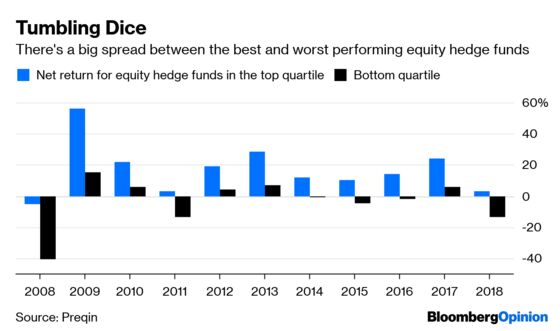

The second is that many high-net-worth individuals, the other big group of hedge fund investors, are incorrigible gamblers. Despite the lackluster performance of equity hedge funds, the best managers among them have delivered eye-popping returns, and investors can’t resist trying to pick the winners.

Consider that the average annual return of the top quartile of equity hedge funds was 17 percent from 2008 to 2018, according to Preqin, compared with just 6 percent for the median. The top quartile also beat the S&P 500 in nine of 11 years since 2008, and by an average of 7.9 percentage points.

But here’s the gamble. The bottom quartile had an average annual return of negative 3.4 percent during the same period. It also lost to the S&P 500 every year, and by an average of 12.4 percentage points. There’s no reason to believe that investors are more likely to pick the winners than losers.

I suspect that many institutional investors will eventually find cheaper ways to manage risk and that high-net-worth investors will tire of sour bets. There are already signs that hedge funds are struggling to find new investors and that some funds are pivoting to better-performing strategies, such as venture capital and private equity. But until investors give up on equity hedge funds in big numbers, they shouldn’t expect better results.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.