Hedge Funds Are Feasting on ESG’s Profit Leftovers

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Asset managers are under increasing pressure to stop investing in companies that worsen the climate emergency through heavy carbon emissions. But recent events suggest that engaging with these companies beats disinvestment as a strategy to improve their environmental performance.

Hedge funds have been making outsized profits buying discarded shares of oil and gas companies, the Financial Times reported last week. Institutional investors “are all so keen to get rid of oil assets, they’re leaving fantastic returns on the table,” Crispin Odey of Odey Asset Management told the newspaper. His European fund has gained more than 100% this year, boosted by investments including Norwegian oil company Aker BP, whose shares have risen by more than a third.

Objecting to hedge funds making money this way is akin to chastising the scorpion in the fable for stinging the frog that carries it over the stream: It’s hardwired into the DNA of traders to seek profits even at the expense of the planet, just as the arachnid is helpless to ignore its fundamental nature.

The broader fund industry should take note. Leaving fat profits on the table for less ESG-minded investors to hoover up isn’t a winning strategy. Savers who’ve entrusted their money to asset management firms are likely to become disenchanted with the green agenda if it threatens to make retirement less comfortable.

Moreover, by starving energy companies of capital, asset managers may be hobbling their ability to fund the transition to a lower-carbon economy. “When you walk away, those assets are still sitting there emitting,” Anne Simpson, the director for governance and sustainability at California Public Employees’ Retirement System, told an online investing conference hosted by MSCI Inc. last week. This is where divesting in the name of climate change becomes a lot trickier than divesting out of so-called sin stocks such as tobacco companies or arms manufacturers.

The debate about whether doing good comes at the expense of returns continues to rage among equity investors. You can find academic studies to back either side, which I fear says more about the difficulty of divining the data than it does about the merits of the underlying dispute.

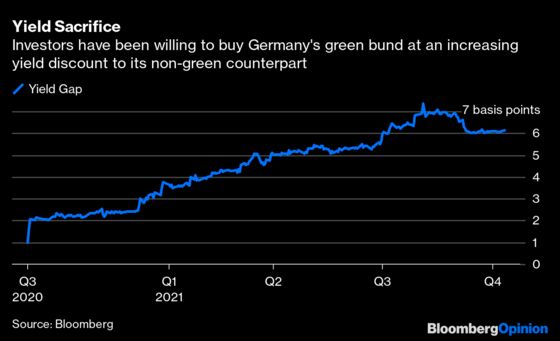

In the bond market, it’s clear that investors are willing to sacrifice returns in exchange for their capital being put to more environmentally friendly uses. Germany, for example, has two government bond issues outstanding that are identical in every way, except the capital raised by one is targeted at environmentally-friendly spending.

When the green version of the bund went on sale in Sept. 2020, its non-green peer was available at a yield 1 basis point higher. Since then, the premium has continued to grow as investors favor the chartreuse alternative. Bondholders are currently giving up about 6 basis points to own the planet-preserving security.

For sure, there’s a supply-demand imbalance at work. At 6.5 billion euros ($7.5 billion), the green bund is dwarfed by the vanilla issue’s 30.5 billion euros. And the universe of potential owners of the former issue is bigger, attracting ESG-dedicated funds in addition to the traditional fixed-income crowd.

But the prospect of raising cheaper finance at a so-called greenium has seen the green bond market explode, with worldwide sales of about $400 billion this year. The first European Union green bond went on sale this week, attracting orders of more than 135 billion euros for just 12 billion euros of securities.

In the equity market, Engine No. 1’s success earlier this year illustrates the benefit of engagement by shareholders. The small fund management firm got three dissident directors appointed to the board of Exxon Mobil Corp. to force the energy company to curb its climate-harming activities.

Calpers, the California pension fund, supported that initiative along with other big funds including BlackRock Inc. by voting its shares in favor of the resolution. “Our next area of responsibility and potential for driving change is boards that are competent with the skills needed,” Simpson said. “We’ve really got to focus on the board of directors.”

Targeting engagement on the most-polluting companies can drive focused results. In trying to calculate the carbon footprint of its $470 billion portfolio, Calpers discovered that just 100 companies are responsible for 85% of the emissions of the 10,000 firms it examined. “If we can through our ownership engage these companies and call on them to set targets for the transition and start putting together strategies, plans for their own transition to net zero, then we’ll get the results that we’re looking for,” Simpson said.

While shunning companies with bad environmental practices is an easier option than trying to persuade them to mend their ways, it can endanger both fund returns and the planet. Capitalism, while remaining resolutely red in tooth and claw, needs to embrace the green agenda.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.