The Bank of England Risks Hiking Too Far Ahead of the Fed

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- That was one sharp hawkish volte-face from the Bank of England. Over the weekend, three Monetary Policy Committee members, including Governor Andrew Bailey, made clear that they are ready to raise rates sooner rather than later. The U.K. government bond market really doesn't like it.

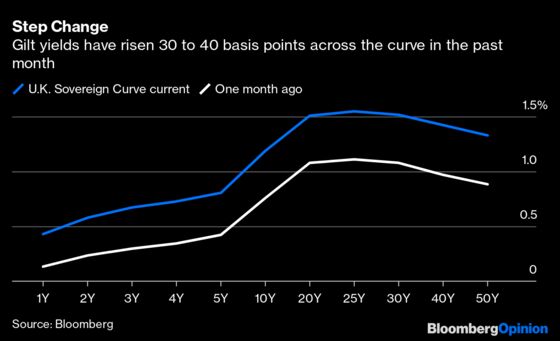

Gilts, which U.K. Treasury bonds are called, have been the worst-performing major fixed-income market over the past two months, with the 10-year yield doubling to 1.2%. That is not a vote of confidence in the Bank of England’s communication efforts.

All of a sudden everywhere the MPC looks it sees inflation. With that come expectations of future price rises — and the fear of suddenly losing control and the prospect of raising interest rates a lot higher than expected.

It is an invidious place for the BOE to find itself. That’s because the world's central banks — with their vast quantitative easing programs — are, in effect, umbilically-linked. The most important of all to the overall direction of rates is the Fed, which is in absolutely no hurry to rein back stimulus. The U.S. central bank will probably start tapering its bond-buying this year but any interest-rate hike could be delayed given American economic and political circumstances.

Furthermore, the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan are still firmly in stimulus mode and several years from contemplating any rate hike. The BOE would win little advantage by acting so far in front of the central bank pack.

Indeed, the U.K. may commit self-inflicted harm by tightening both monetary and fiscal policy at the same time. That would be especially true if the pandemic recovery peters out because of a China slowdown or an energy price shock that kills demand. Then Britain would have undermined all the slow but steadily herculean heavy-lifting of its stimulus efforts. Stop-start is rarely beneficial especially as the U.K’s biggest competitors on either side of the Atlantic are continuing to pour in increasing amounts of fiscal stimulus along with super-benign monetary environments — it risks making global Britain a less obvious place to do business.

What’s behind this hawkish BOE shift? A lot of popular hysteria about inflation and stagflation. The Economist's Duncan Weldon eloquently argues there are real problems measuring inflation. And the gnashing of teeth about imminent stagflation looks wildly misplaced. The overlooked element to this thesis is unemployment, which for the U.K. at 4.6% is not far away from pre-pandemic levels and likely to fall further. There is no sign of anything like the stasis of the 1970s. U.K. growth this year is likely to be above 6% — leading the G7 — and inflation is not rising at the same pace as the U.S.

The panic is irrational. The BOE has been in stimulus mode for too long without having its faith challenged. But, now, faced with seemingly alarming events, it has lost its religion that inflation is purely transitory. But hiking interest rates is not going to lower the price of natural gas, train more truck drivers or produce more computer chips. It is overseas cost-push inflation that overwhelmingly affects the supply side; so, why respond with a blunt demand-side hammer? George Buckley, chief U.K. economist for Nomura International, argued in the Times of London that fighting inflation might be the wrong call.

But the hawks in the MPC have been heard. There is now a 15 basis point interest-rate hike priced in by the money markets before the end of the year — with potentially a second raise of 25 basis points to follow in swift order. On Monday, Bank of America Corp. changed its call and now says rates will be at 0.50% by February. That could combine unpleasantly with a planned first-quarter fiscal tax tightening from the government, slamming the brakes on the nascent recovery.

At the last monetary policy meeting only two of the nine MPC members voted to bring the pandemic stimulus program to an end, with all voting to maintain the official bank rate at 10 basis points. Yet Bailey has not used the opportunity to row back on market speculation of a rate hike, though he could have calmed markets ahead of the next monetary policy review on Nov. 4. Indeed, even by then, the BOE would have little of the necessary data to make an informed decision. It will not yet have insight into how the end of the furlough employment support package is affecting the job market. Neither will it have a substantive inflation update. Relatively speaking, the Bank is flying blind.

Crucially, the first move in any interest-rate cycle needs to be handled with the utmost care; if money-market institutions are blindsided to a sudden change in rate expectations they will rush to hedge their exposure. Hence, the sharp rise in Gilt yields.

Nobody doubts the need for the Bank to withdraw stimulus. It is bizarre for it to be still planning to buy 3.5 billion pounds ($4.75 billion) each week to the end of this year. But there needs to be a clear game plan on how far and how fast rates are adjusted upwards to avoid unnecessary fallout. Facts change — as with sudden surges in inflation — but the reaction function needs to be smooth and mindful of how the U.K. co-exists with the rest of the world.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.