H2O’s Reach for Yield Sounds an Industry-Wide Alarm

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Enter the phrase “reach for yield” into Google, and the search engine will return 335,000 results in less than a second. So no-one should be blindsided by the revelation that investment managers have been tempted to boost returns by buying riskier securities in recent years. Regulators should still be asking hard questions right now of the portfolio managers they oversee.

H2O Asset Management, a unit of French bank Natixis SA, is seeing billions of euros head for the door after the Financial Times reported last week that the fund had bought a bunch of bonds linked to entrepreneur Lars Windhorst.

While the firm was transparent in reporting the securities it held, it took the FT to trace the threads between an Italian lingerie maker and a German real estate company and link them back to Windhorst. To investors, it looks like H2O loaned a large sum of money to the entrepreneur, dressing its actions up as a series of uncorrelated investments in private bonds sold by a diverse range of companies.

Announcing a package of measures intended to stem the withdrawals, Natixis said on Monday that the fund had switched to “record these securities at their transactional value in case of an immediate total sale, rather than recording them at their standard market value.”

I have no idea what the alleged standard market value for such illiquid securities would be and, I would suggest, neither does H20, no matter how hard it worked its spreadsheet to perform whatever cashflow analysis it could on Windhorst’s companies. But after “valuations obtained this Sunday from international banks,” H2O has revalued its holdings.

H2O isn’t saying what the new, lower “transactional” valuations are. But the drop in the bonds’ aggregate weighting in the funds to less than 2% of assets under management, down from as much as 9.7% less than a week ago, gives some flavor of the discounts being applied.

The move suggests Bruno Crastes, H2O’s co-founder and chief executive officer, is considerably less ebullient about those unlisted investments than he was in a video posted by the H24 Finance news service on Friday. In the English transcript of that interview supplied by H2O’s public relations firm, Crastes says that “obviously there is no reason for us to not continue in the future to invest in those private bonds.”

That didn’t stop his firm from selling about 300 million euros ($342 million) of the private placements at the end of last week, according to my colleagues at Bloomberg News. Presumably the price those sales fetched is closer to the values produced by Sunday’s ringing around, rather than the market values ascribed to the bonds a week ago.

But there’s a wider issue here than one fund manager juicing its returns. The reach for yield referred to at the start of this article is likely to have become even more desperate in recent years – and financial regulators need to be on their toes to safeguard the public from portfolio managers playing fast and loose with what counts as a liquid investment.

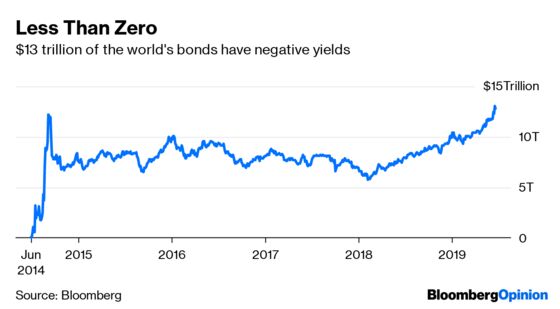

Some $13 trillion of what we still laughingly refer to as the fixed-income market currently generates negative yields, meaning the only fixed aspect of the securities is that buyers end up paying for the privilege of stashing their cash in bonds:

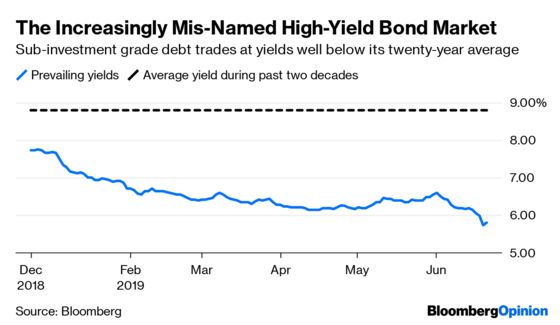

Even the $2.4 trillion global market for high-yield bonds is undergoing something of an identity crisis as non-investment grade debt offers less than two-thirds of the average yield investors have enjoyed in the past twenty years:

With yields on government bonds at record lows in several countries, the temptation to roll down the credit curve into lower- or even non-rated fixed-income securities becomes harder to resist. And the risk of investors getting spooked and all heading for the exit at once has been shown to be a clear and present danger by the recent exoduses endured by H20, Neil Woodford and Swiss asset manager GAM Holding AG.

Financial markets are built on several different types of origami. They range from the relatively simple maturity transformation of borrowing short-term money and lending it for a longer period, to more complex engineering such as collateralized debt obligations that slice securities into different risk buckets.

Liquidity transformation, though, arguably poses the biggest risk to investors, since it can lead to their hard-earned capital being trapped in investments that turn out to be far harder to sell than the marketing brochures might have you believe. Here’s where the shoe has pinched three times in the past year; so liquidity, or rather the lack thereof, is exactly where regulators should be focusing their attention, to unearth any landmines before stretched valuations in the credit market cause the next financial crisis.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.