Grounding the 737 Max Eases Turbulence for Airlines

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The grounding of Boeing Co.'s 737 Max after a pair of accidents killed 346 people might seem an unmitigated disaster for the world's airline industry. Look at flight data, though, and you can glimpse a grim benefit supporting carriers' bottom lines.

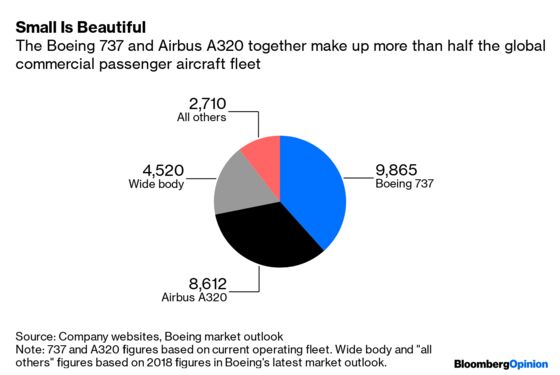

To see why, it’s worth remembering just how crucial the 737 and its arch-rival, the Airbus SE A320, are. Each plane family constitutes about a third of the roughly 24,000-strong global passenger airline fleet. Other aircraft put together – including all wide-body planes like the 747, 787, A330 and A380, turboprops and smaller jets like the Bombardier Inc. CRJ – make up the remaining third. According to Boeing, a 737 takes off or lands somewhere in the world every 1.5 seconds, and there are about 2,800 in the air at any one time.

If anything, that probably underestimates their importance in terms of air traffic. Narrow-body aircraft like the 737 and A320 fly shorter distances and are turned around more times. In the U.S., they depart from airports roughly two to three times a day for every time a wide-body jet takes off, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Airline Data Project. By a very rough back-of-the-envelope estimate, the two aircraft together account for about 80% of global departures.

That matters because one of the most important determinants of airline profitability is load factor, the share of seat capacity filled by paying passengers. Flying planes involves very high fixed costs, but once more than about 70% of seats are filled, the marginal cost of dealing with an additional passenger will be far outweighed by the revenue to be earned from selling the ticket – one reason that last-minute bookings can be such good value.

Load factor, in turn, is largely a function of whether airlines have over-estimated or under-estimated the pace of passenger traffic growth, and how that relates to the capacity they’re putting into the market by buying or leasing planes and using them more or less frequently.

This year has been an uncertain one for carriers on that front. The impact of the trade war and general darkening economic outlook has meant that the International Air Transport Association’s forecast from the end of last year of a 6% pace of passenger traffic growth is likely to be a significant overestimate. In the first six months of the year, the increase was just 4.7%.

But capacity has instead grown by just 3.3% from a year earlier in the most recent three-month period – in no small measure because of what’s happening to the 737 Max.

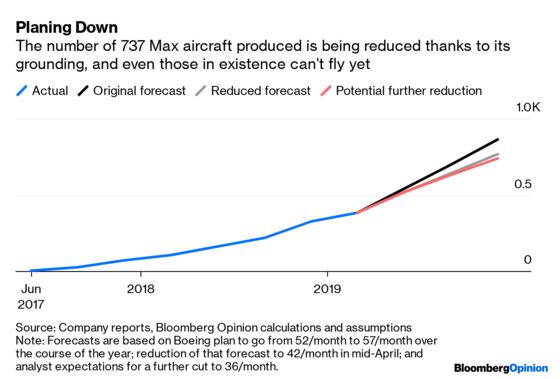

The worldwide grounding of the aircraft in March following accidents in Indonesia and Ethiopia took 387 aircraft out of service at a stroke. Had original plans to gradually increase production to 57 aircraft a month this year gone ahead and deliveries kept pace, there could have been nearly 900 in the skies by the end of 2019. As it is, Boeing is still struggling to fix software and clear regulatory demands, and operators are now drawing up their schedules as if it won’t be flying until December or even next year.

There is, to be sure, a certain amount of slack in the commercial-jet market. Some of those new 737s would have replaced older models that might have gone out of service altogether – but most older planes leaving airlines’ fleets would have been sold on to leasing companies and rented, so there’s still a marked tightening in the market. If the planes remain grounded through year-end, nearly 10% of the global 737 fleet that airlines expected to be in operation this year will be out of action.

That appears to be tightening the supply of seats. Industry-wide load factors hit record seasonal highs in April, May and June, according to IATA. July load factors were the highest for that month in any year barring 2017, according to separate data compiled by Bloomberg, and short-haul load factors that month were the best ever. As a result, the industry appears to be riding out the ongoing fall in ticket prices which has pushed revenues per passenger, per kilometer, down 2.9% over the past year.

The 737 Max scandal has been one of the darkest clouds the airline industry has flown through. So far, though, it’s staying aloft.

Of 22 airlines with load factors of 81% or below in the most recent financial year, just seven reported more than a few million dollars of net income, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Patrick McDowell at pmcdowell10@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.