Green Bank Tests Are Like the Metaverse: Mostly Fantasy

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Just like Facebook’s Metaverse, stress testing banks for climate-change risks is mostly fantasy. There is a lot that lenders and regulators still need to build to realize this vision.

Unlike Mark Zuckerberg’s parallel life, it really matters in the real world if banks don’t develop the right tools.

Big European banks supposedly face their first thorough climate-risk stress tests next year. The European Central Bank has produced an extensive spreadsheet for lenders to fill in. It has a long list of narrative questions about banks’ approaches to climate risk and it asks for borrower-by-borrower data on their greenhouse gas and carbon dioxide emissions, both their volume and intensity.

But the dirty secret of this ambitious exercise is that few banks can complete it. Many have barely begun to develop systems for collecting and analyzing this stuff and many of their borrowers don’t produce the kind of numbers that banks need.

But that doesn’t make the ECB’s effort a waste of time, nor does it mean U.S. and U.K. regulators should abandon their work. The point is to keep up pressure on lenders and their clients.

I asked some banks’ chief financial officers during recent third-quarter results calls what they think is possible. Most are confident they have high-level data that broadly outlines the emissions in their portfolios, but not necessarily the kind of granular detail across industries that the ECB wants. And among small and medium-sized companies, they have very little data at all.

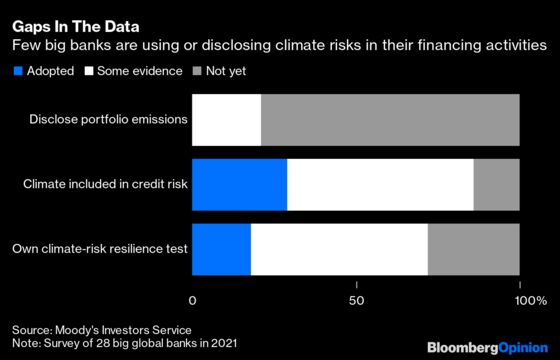

Other research backs this up: It shows few among even the world’s biggest banks have tried to run their own tests to check climate-risk resilience in their loan books. Only five of 28 multinational banks from the U.S., Europe and Asia have done this, according to a new study from Moody’s Investors Service.

“The banks' generally limited ability to measure the carbon footprint of their loans and investments makes it harder for them to gauge their own vulnerability to climate change,” Moody’s said in a report published Tuesday.

Only six of these big banks report any climate effects from their financing, the ratings firm found. And even then, it isn’t always comprehensive.

In the U.S., JPMorgan Chase & Co. is producing data on average carbon intensity from clients in a handful of sectors: carmaking, electric power and oil and gas. Barclays in the U.K. is doing something similar.

Research from Citigroup found few European banks disclose any such data. Its analysts point to just four examples: ABN Amro Bank and ING Group of the Netherlands, Credit Agricole of France and Raiffeisen Bank of Austria.

This lack of capability hasn’t stopped banks making bold promises. More than 450 institutions have committed to cut emissions across their portfolios by signing up to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero — co-chaired by Michael R. Bloomberg, the owner and founder of Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP, and former central banker Mark Carney. The pledge includes a 50% reduction by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050.

But even regulators at the Bank of England, early proponents under Carney of assessing climate risk in finance, are now expressing doubts about what’s possible. The Prudential Regulatory Authority, part of the BoE, highlighted “credibility gaps” in data and modeling techniques in a report last month. It also isn’t sure that either its bank-specific microprudential approach or its system-wide macroprudential one was well suited to the task of counteracting climate risks. The micro is too short-term, while the macro is geared toward recurring, cyclical risks in finance rather than dangers that build slowly over time toward potentialtipping points.

And yet, both the ECB and BoE are threatening extra capital charges to mitigate climate risks from next year. Why? Ostensibly, it is ensuring banks have the right cushion against risk and not about trying to direct what loans banks make. But for now, it’s really a punishment for those not doing their homework.

British banks will have to show they are using what judgment, expertise and tools they do have to understand and manage climate risks. For the ECB, the 2022 stress test is really an exercise is discovering what is possible: what banks can do and what good or bad practices already exist.

In both markets, the banks that aren’t making enough effort, or that don’t even have an approach, will face extra capital demands. That might seem unfair. It is certainly inexact. But alongside government policy, finance is a fundamental mover of the economy and what happens in it.

That makes banking important. It is funding a world that, unlike the metaverse, we have no choice but to inhabit.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.