(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The European Parliament elections were meant to mark the high point of populism in Europe. Instead, they may have led to the political demise of its earliest champion: Alexis Tsipras.

Greece’s prime minister, who stunned the continent with a double win in consecutive general elections in 2015, has called a snap vote that will probably be held at the beginning of July. His far left Syriza party, which has dominated Greece’s politics for the past four years, suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the center right New Democracy. That party, headed by the reform-minded former McKinsey consultant Kyriakos Mitsotakis, won more than 33% percent of the vote, while Syriza only took about 24%. A national election was due toward the end of this year. Tsipras may have concluded that an early vote is the best way to limit the size of an inevitable defeat.

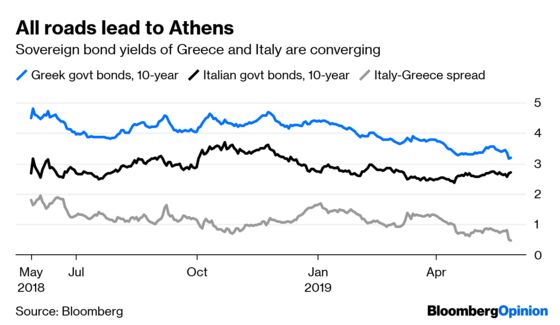

The announcement of a new election – and the strong showing from New Democracy – has enthused investors. The yield on Greece’s 10-year bond fell to 3.08% from 3.33% on Monday (before rising slightly to 3.14% on Tuesday morning) and the country’s stock market was up about 6%. The best indicator of the financial markets’ renewed confidence in Greece is the spread with Italy’s bonds, which is now less than 50 basis points. At the start of the year, it stood at about 170 points.

Greece’s economic and financial challenges remain formidable, of course. Athens can borrow at very favorable rates, thanks to the support of its euro zone partners. But sovereign debt still stands at 181% percent of national income. The economy expanded by a healthy 1.9% in 2018, more than France, Germany or Italy. But income per capita is still 21% lower than it was in 2008, according to Eurostat data. With the banking system under-capitalized and stuffed with non-performing loans, the economic situation remains challenged (to put it mildly).

Nevertheless, the increasing appetite for Greek assets makes sense too. When I visited the country in December, I left with the impression that politics was returning to normal. Syriza and New Democracy were both looking ahead to the future, offering a clear choice between those who prefer greater redistribution and those who favor lower taxes and more economic reform.

Now we have a sense of what the Greeks themselves appear to want. The country’s politicians have a habit for raising expectations and then crushing them, but Mitsotakis’s political platform, which includes steep reductions in corporate tax rates funded via some spending cuts, looks level-headed. Greece has committed to running comfortable primary surpluses for decades, and it’s unclear whether New Democracy will actually stick to that pledge once in power. But the lesson of the past decade is clear: If Greece can reform its economy and achieve sharply higher economic growth rates, there is no need for excessive belt-tightening.

It’s not just investors who should celebrate. Tsipras has been hailed for his decision to step back from the brink of leaving the euro, and achieving a second mandate after signing a new rescue program with Greece’s international partners. He was also brave in ending a decades long standoff with the newly renamed North Macedonia. This decision probably cost him politically, but won him plaudits globally.

But it’s impossible to forget that Tsipras’s rise to power was built on deceit. When he won his first term at the start of 2015, he did so by pledging that he would keep Greece in the currency union while making its euro zone partners concede much better terms for a new rescue plan. Instead, he plunged the country into a new self-inflicted recession, forcing Greek citizens and businesses to live with capital controls. He then went back on his earlier confrontational stance, ditching his more radical allies, including finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, to sign an agreement where he won hardly any concessions.

That voters have decided to punish Tsipras for all of his U-turns is welcome. The dark side to Europe’s populists is not their criticism of the poor functioning of the EU, which is plain for everyone to see, but their relentless dishonesty over what can be achieved while negotiating with other member states. This puts Syriza in the same camp as Britain’s Brexiters and Italy’s League and Five Star Movement; with the latter two settling for minimal fiscal expansion in their 2019 budget having promised a gargantuan stimulus.

Voters may have had enough of mainstream parties, but they’re not blind to the failings of newcomers. Tsipras was a pioneer among the populists and he’s one of the first to risk being booted out. In a week of mixed results for anti-establishment forces across the EU, they should reflect on his experience.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns and editorials on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.