(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If you want a snapshot of how far the euro zone has come, look no further than Greece and Italy.

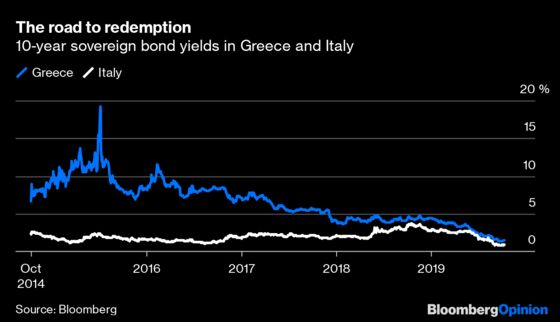

Until recently, the two Mediterranean countries have been considered the sick men of Europe, as investors demanded hefty premiums to hold their sovereign bonds. These extra charges were all the more striking given the steep fall in the yields of other countries that had been engulfed in the sovereign debt crisis of the early 2010s, namely Spain, Portugal and Ireland.

Greece and Italy have finally joined the party too, but there are still reasons to be skeptical. The two countries continue to suffer from very high levels of public debt, which weak economic growth has failed to erode. And while the financial markets seem to like the new governments in Athens and Rome, there is a risk that these administrations prove too optimistic in their forecasts for how fast their economies will expand and how quickly their budget deficits will shrink.

Last week saw symbolic moments for both countries. Greece issued new three-month debt at a negative yield for the first time, joining a growing list of countries in Europe and beyond which enjoy the privilege of being paid to borrow money. Meanwhile, Italy sold dollar-denominated bonds for the first time since the start of this decade. The auction was a resounding success, as Rome placed $7 billion of debt on the market, more than double an initial estimate, after receiving orders of more than $18 billion.

In both cases, the successful bond sales crown months of extraordinary comeback. A 10-year Greek bond yielded more than 3.5% in mid-May, with a spread of over 360 basis points compared to Germany. It now yields less than 1.5%, as the spread has fallen below 200 basis points. Over the same time period, Italy's 10-year bond has fallen from around 2.7% to below 1% today. The spread with bunds of similar duration has halved from around 280 basis points, to roughly 140 basis points.

This amazing run can be partly explained thanks to the European Central Bank. Since last spring, the ECB has veered towards a more expansionary monetary stance. Last month, outgoing President Mario Draghi announced the central bank would cut its deposit rate deeper into negative territory and resume its program of net asset purchases, all of which has clearly contributed to pushing down bond yields.

But Italy and Greece are also benefitting from the arrival of their new governments. In Rome, the center-left Democratic Party has replaced the hard-right League as the governing party with the Five Star Movement. The new coalition has taken a much less confrontational stance vis-à-vis the rest of the EU, reassuring investors that there is really no chance of Rome leaving the single currency. In Greece, the center-right Kyriakos Mitsotakis has replaced the hard-left Alexis Tsipras as prime minister, on a platform of cutting taxes and enticing investment. Investors hope the country can finally bounce back after the never-ending recession of the last decade.

And yet, one should not get carried away in either place. Greece's public debt stood at over 180% of national income at the end of 2018, while Italy's was still nearly 135%. Rome and Athens have no problem in rolling over their bonds at very favorable interest rates. But the question is whether they will be able to lift their growth rates enough to make these burdens more sustainable, especially at a time of extremely low inflation.

The other issue relates to the credibility of the two governments. Italy's new administration is targeting a 2.2% budget deficit for next year, which is in line with this year's level. However, it has penciled in most of its extra revenues from measures to fight tax evasion, which are often unreliable. Greece is projecting very optimistic growth rates for next year, well above the forecasts from the European Commission. Much will depend on whether the investment boom Mitsotakis is counting on actually materializes.

For all the gloom surrounding the prospects of the euro area, Italy and Greece represent two reasons to be moderately cheerful. But as these lands of history know all too well, it can take much longer to rise than to fall once again.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.