(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A decade ago, less than a third of the people in developing regions had access to fast mobile internet connections. This “coverage gap,” as it came to be known, was a worrisome phenomenon, especially to governments keen to compete in the knowledge economy and tech companies eager to profit from it. So in 2013, Alphabet Inc.’s Google announced Loon, a “moonshot” project to provide internet to rural and remote regions using high-altitude balloons.

Seven years later, 93% of the planet has access to mobile internet, which sounds like a huge success. Yet Loon announced in January that it was shutting down. What happened?

From the start, challenges abounded for the project, including significant technical hurdles and the emergence of other, competing means of providing mobile internet. But ultimately, Loon didn’t take off because Alphabet failed to recognize that socioeconomic problems — including illiteracy, the cost of data and handsets, and discrimination — would play a bigger role in keeping people off the internet than a lack of cell towers.

Back in 2010, Google’s founders announced an R&D arm, called Google X, that would aim to make the world a “radically better place.” Expanding internet access to those who don’t have it was a problem that fit well into the portfolio. The impediments, as Loon saw it, were primarily low-tech — “jungles, archipelagos, mountains” — and thus well-suited to its innovations.

The result was a far-out Wi-Fi network flown on high-altitude, AI-controlled, tennis-court-sized balloons. Astro Teller, the “captain of moonshots” at the company, gave it a 1% or 2% chance of success initially. But for cash-flush Google, the potential payoff was worth the risk. Success would achieve a social good (universal internet access) and lead to a profitable new business. In 2017 Loon provided emergency connectivity to Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria, and in 2020 it began offering 4G-speed connections to a remote segment of Kenya.

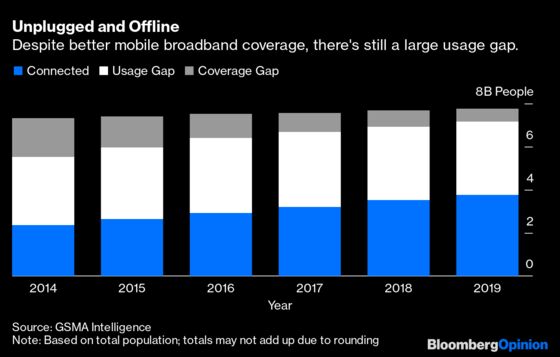

The latter was an impressive achievement, but it came much too late. Over the past decade, mobile broadband access has expanded rapidly across emerging markets, reducing costs. But even as the coverage gap narrowed, a persistent “usage gap” remained. According to GSMA, the global trade association for mobile network providers, there are still some 3.4 billion people living in an area with a mobile broadband network who aren’t using any mobile internet.

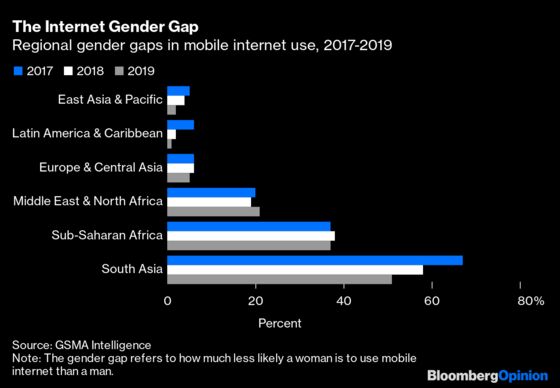

What’s keeping them offline? Surveys consistently cite illiteracy and a lack of digital skills. No surprise, both problems are closely related to underdevelopment. In 2019 the median cost of an entry-level internet-capable phone in sub-Saharan Africa was more than 120% of income for the poorest 20%. Gender disparities also play a role. For example, women in South Asia are 51% less likely to use the mobile internet than men, thanks to a lack of financial autonomy and disapproval in more traditional cultures.

No tech company can fully close this gap. But that doesn’t mean they’re helpless. If Google’s goal is to expand the use of mobile internet, it could lobby governments in emerging markets to reduce barriers to the import of low-cost used electronics. It could also follow the lead of India’s Jio Platforms Ltd. and offer cheap feature phones in low- and middle-income countries. The JioPhone, introduced for less than $20 in 2017, has sold more than 100 million units, and contributed mightily to closing India’s usage gap.

Reducing illiteracy and improving digital skills will be more difficult. But tech companies could help by developing voice-based interfaces for low-cost phones. Google could also expand its U.S.-based efforts to boost digital skills training in poorer countries. More ambitiously, it could partner with local organizations and governments to fund adult literacy programs in regions — such as sub-Saharan Africa — where illiteracy runs high.

None of these steps will advance Google’s reputation for cutting-edge technology. But over time, they’re the sort of thing that actually could make the world a “radically better place.” They could also ensure that the company’s next invention targeted at emerging markets doesn’t pop like an over-inflated balloon.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Adam Minter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is the author of “Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade” and "Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.