Goldman Sachs Traders Slow Down, But the Bank Doesn't

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s traders set an impossibly high bar for themselves to clear in the second quarter. As expected, they couldn’t keep up that kind of frenetic pace in the three months through September. But the bank didn’t need them to.

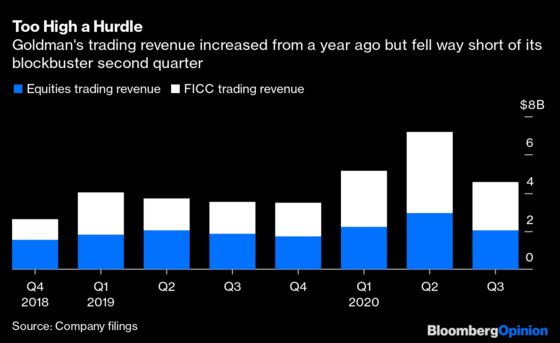

That’s not to say Goldman’s traders were slouches. Far from it, in fact — trading revenue in fixed income, currencies and commodities jumped 49% from the same period in 2019 to $2.5 billion, the biggest year-over-year increase on Wall Street so far and topping analysts’ estimates for $2.27 billion. Equities trading revenue was $2.05 billion, missing estimates for $2.14 billion but still up 10% from a year ago. And yet those numbers look positively pedestrian compared with Goldman’s blockbuster second quarter, when FICC trading revenue soared 149% year-over-year and equities trading rose 46%, the division’s best performance in 11 years.

All told, on a quarter-over-quarter basis, Goldman’s FICC trading revenue fell 41%, more than that of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc., while equities tumbled 30% in what will probably be the biggest drop on Wall Street. While traders accounted for more than half of the bank’s revenue in the second quarter, global markets claimed just a 42% share in the period ended Sept. 30.

In previous years, this kind of slowdown could have eroded Goldman’s overall earnings. Not anymore: The bank’s earnings per share were a record $9.68, blowing past analysts’ estimates for $5.53. Net income almost doubled from the same period in 2019, to $3.62 billion. Its 19% return on tangible common equity was “best in class relative to other banks that reported so far,” said Christian Bolu of Autonomous Research. Its shares, which have declined less this year than more retail-focused competitors, surged 3% in pre-market trading.

The results appear to validate Chief Executive Officer David Solomon’s longer-term strategy of diversifying into retail banking and sharpening Goldman’s focus on wealth and asset management. Its consumer division reached $1 billion in trailing 12-month revenue for the first time since it launched four years ago, posting a steady 13% year-over-year gain and a 10% increase from the prior quarter. Asset-management revenue is up a stunning 71% from the same time in 2019 and 32% from just the second quarter, which the bank chalked up to “significantly higher net revenues in Equity investments and Lending and debt investments, and higher Management and other fees from the firm’s institutional and third-party distribution asset management clients.”

As Bloomberg News’s Sridhar Natarajan has reported, Goldman’s goal is to manage more client money — rather than its own — to generate a steadier income stream. That includes a new $14 billion credit fund, which would be its largest since the 2008 financial crisis and represent one of the largest debut investment vehicles ever raised. The bank has set a target to raise another $100 billion in new capital to deploy in alternative investments like distressed credit, private equity and real estate.

That kind of investing is risky, of course, but in a much different way for Goldman than revenue from trading bonds and stocks, which depends on big price swings to drive greater volume. Volatility can create more opportunities to purchase alternative assets on the cheap, but the allure for Goldman is the years of fees it can extract from investors who will pay up for access to otherwise hard-to-reach markets.

To be sure, traders are still crucial for banks as the coronavirus pandemic creates questions for investors about the U.S. economy. For evidence of that, look no further than Bank of America Corp., which posted just $3.36 billion of trading revenue in the third quarter, up just 3.6% and missing estimates for $3.5 billion. “We lost a little share because we don’t take the same amount of risk,” Chief Executive Officer Brian Moynihan said on a conference call. Stephen Scherr, Goldman’s chief financial officer, said on an analyst call that he didn’t “see our risk as being unusually elevated in the context of producing these kinds of results,” adding that the bank “picked up meaningful market share” that should carry over into the coming years.

At Goldman, trading accounted for 35% to 40% of its overall revenue from 2017 to 2019, down from 45% to 50% in the previous five years, according to Alison Williams of Bloomberg Intelligence. Remarkably, even with that 10 percentage point decline, it’s still far more sensitive to trading revenue than all U.S. and European peers — the median figure for trading as a share of total revenue across the industry is just 21%. Goldman’s third-quarter figure of 42% means that its traders still have outsized importance, even relative to just a year or two ago.

If all goes well in the fight against Covid-19, it’s reasonable to expect that trading gains at the biggest U.S. banks will slow down from their blistering 2020 pace. For the reinvented Goldman, on the other hand, it looks like full steam ahead.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.