(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As the pandemic keeps huge swathes of the global economy in lockdown, companies are curtailing or suspending their dividend payments. At the same time, longer-dated bonds — issued back in the day when interest rates were still positive — are being repaid as they mature. For pension funds, which have long-term obligations to fund the retirements of their savers, it’s a dreadful combination.

Earlier this week, JPMorgan Chase & Co. set aside $8.3 billion to cover the anticipated cost of consumers not paying their credit cards and companies not making their loan payments, its biggest bad-debt provision since the global financial crisis. Its analysts published a separate report estimating that global corporate profits will “crater” by 72% by the middle of the year, and will remain 20% below pre-virus estimates by the end of next year. If companies aren’t making money, they can’t pay dividends to shareholders.

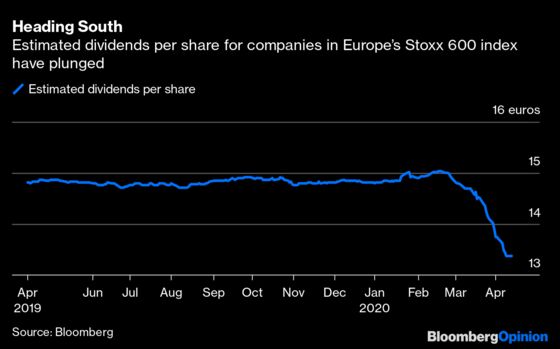

So about a quarter of the companies in Europe’s Stoxx 600 benchmark index have scrapped or postponed dividends so far, according to calculations by my Bloomberg News colleagues Lukas Strobl and Kasper Viita. Estimated dividends per share have slumped accordingly.

The various state-aid packages available around the world are likely to come with strings attached, including an obligation to suspend payouts. On Tuesday, for example, German sportswear company Adidas AG said it won’t pay any dividends after getting an aid package worth 3 billion euros ($3.3 billion) from its government and a syndicate of banks.

The total of canceled payouts across Europe has reached $52 billion, income that won’t be flowing into pension schemes or other savings and investment products. That’s likely to rise further as more companies adjust to their newly straitened circumstances.

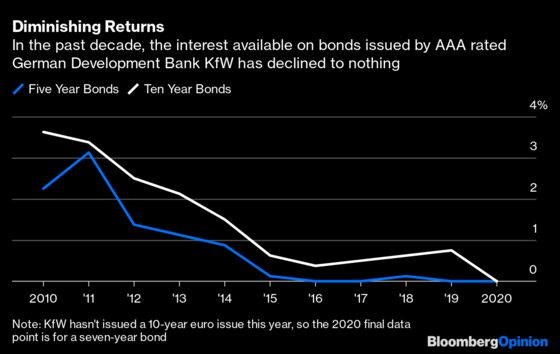

And it coincides with the end of older fixed-income investments that offered a combination of top quality and an income stream. In 2010, for example, a pension fund could have invested in 5 billion euros of five-year bonds issued by Kreditanstalt fuer Wiederaufbau, the German state-owned development bank also referred to as KfW. Those bonds, with top AAA ratings, paid an annual interest rate of 2.25%, meaning that a bondholder with 1 million euros of the securities would have received 22,500 euros every year.

When the borrower repaid those bonds in 2015, the fund could have reinvested in 6 billion euros of new five-year bonds. The interest rate, though, had declined dramatically, to 0.125%. So the new investment would have delivered just 1,250 euros of annual income for every 1 million euros invested.

It gets worse. Those bonds are scheduled to mature in June, at which point the fund could reinvest in 5 billion euros of five-year notes KfW sold in January — which pay an interest rate of precisely zero, nada, diddly-squat, nothing.

As the chart above shows, even buying longer-dated securities sold by KfW hasn’t offered much protection from the relentless downward momentum of interest rates. The 36,250 euros of annual income a fund could have received by buying 1 million euros of 10-year bonds a decade ago ended when those bonds were repaid in January.

Oh, and that five-year issue KfW sold in January that pays zero interest? It trades at about 101.25 for a yield of -0.26%. In other words, a pension fund buying the notes today is absolutely guaranteed to lose money if held through to maturity in 2025.

There’s little prospect of yields and interest rates on fixed-income securities heading higher anytime soon what with the world’s central banks restarting and escalating their various bond-buying programs — the Federal Reserve even going so far as to lend support to companies that have recently dropped into the junk rating category.

It’s a far worse scenario than what happened in the last financial crisis, as Anthony Peters, an independent market consultant, points out. “In 2008, investment portfolios were still full of legacy fixed-income portions which paid a proper income and which largely covered the dip in dividends,” Peters wrote in his daily email note this week. “They’re gone now and have been replaced with, in the case across Europe, bonds with no to negative coupons.”

Retirees, both current and future, need money on an ongoing basis. It’s helpful if the particular funds they’ve invested their nest eggs in beat the relevant benchmark, but absolute returns count for more than relative performance.

The current drop in income as companies suspend their dividends comes at an even worse time for pension funds than during the global financial crisis. Our working lives probably just got even longer.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.