Germany Should Prod Its Savers to Take a Few Risks

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The German government is often accused of spending too little money. With interest rates low or negative, the thinking goes, Europe’s biggest country should be using its fiscal discretion to stimulate the region’s economy.

But then, German households exhibit similar behavior. Even as rates fell, they saved as much as ever, more than people in most other rich countries, and they’ve tended to stick with bank savings accounts or cash instead of yielding to the temptation to invest in potentially more rewarding stocks or bonds.

This isn’t necessarily as irrational as it sounds. German saving behavior is somewhat typical of Europeans in general and is driven by a lack of trust in the uncertainty of financial markets. But, given the predicted private investment slump, it might be worth it for the government to try to lure German savers out of their protective shells and stimulate more investment in equities and corporate debt.

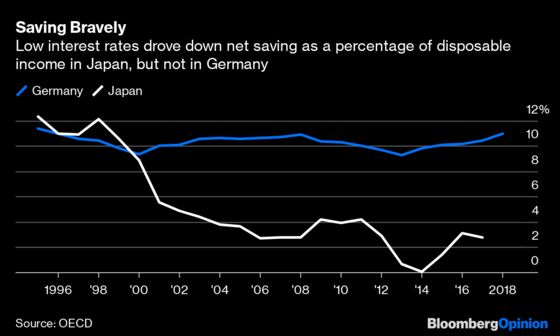

Germans have always been among the most avid savers in Europe. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, they hold on to about 11% of their disposable incomes, compared with less than 7% for Americans and 0.4% for Britons. Even the near- and below-zero interest rates of the years following the global financial crisis haven’t discouraged them from putting so much money aside, as happened in Japan during its ultra-low-rate era of the last two decades.

But then, German saving behavior is somewhat typical of Europeans since the crisis. In a paper for the Estonian Central Bank last year, Natalia Levenko showed that in 24 European countries, saving rates over the last two decades haven’t responded much to interest-rate policies, reacting, instead, to the perception of unemployment risks. Germans and many other Europeans (Britons are among the few exceptions) believe in saving for a rainy day regardless of what governments and central banks do — and don’t believe in replacing savings with cheap credit when it comes to consumption, a choice many Japanese appear to have made.

From that point of view, the saving rate of Germans isn’t unreasonable or a cause for worry. The country has a relatively low household-debt level — 95% of net disposable income, compared with 109% in the U.S. and 146% in the U.K. — and the average German lives less precariously than the average American or Briton. That’s a good thing, a cushion in case of crises. The problem is what Germans do with their savings.

Their nonfinancial assets, such as real estate, make up 58% of their total wealth, compared with 39% for Americans. That traditional preference has meant sharp increases in real estate prices in German cities in recent years. But then, only 48% of German households own any real estate, so the boom has passed many by, even hurt them with increased rents, causing a political backlash that has led the Berlin government to legislate a five-year rent freeze this year.

Almost 38% of Germans’ financial assets are held in the form of cash and bank deposits. At the end of September, German households held a staggering 540.5 billion euros ($597 billion) in deposits with a duration of three months or less. This amount is only slightly lower than the all-time record of 543.8 billion euros, set in April of this year, even though it’s drawing record-low annual interest of just 0.12%.

That’s a political problem, too: Savers and the right-wing parties that profess to speak for them fault the European Central Bank for its loose monetary policy, blaming it for driving down interest income for hard-working Germans. The truth, however, is that the savers themselves are behaving too conservatively for their own good. According to a survey published earlier this year, 64% of German savers haven’t reacted to low rates at all. The 36% who did were wealthier and more educated people — but, according to official statistics, despite their more adventurous investments, securities still make up a smaller share of household financial wealth than in 2008.

That’s not a purely German phenomenon, though. Earlier this year, two German economists published a study of returns on European households’ investments between 2008 and 2017. They found that since the financial crisis, Germans have increased the share of cash and deposits in their financial assets — but not as much as euro area residents did on average.

Saving behavior in Germany and most of Europe is partly habit but mostly a legacy of the financial crisis. As Chancellor Angela Merkel said at the World Economic Forum in Davos early this year, the crisis “is still in our bones.” She added, “It has cost an incredible amount of trust in politics but also in business, especially in the financial sector.”

One can’t fault Merkel for complaining, but it’s up to the German government to lead its European peers in trying to persuade savers to tolerate a little bit more risk for the sake of profit. More investment would boost private development of technology, an area in which Germany risks falling behind the U.S. and China. Tax breaks for securities investors, especially smaller ones, could spur a shift from low-interest deposits — and provide incentives for more companies to go public. It’s time to fight the post-crisis legacy of mistrust more actively than the German and other European governments have been doing. Time heals, but it needs some help.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.