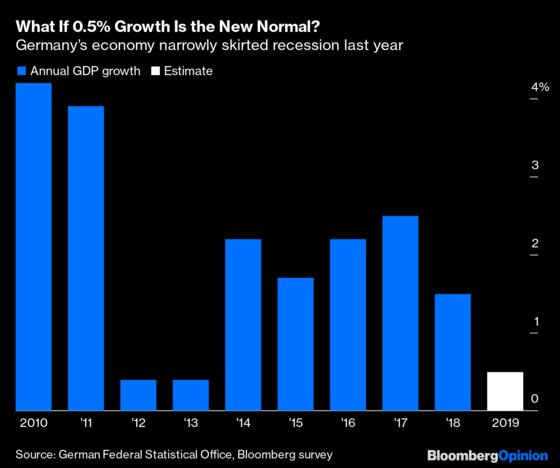

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The cognoscenti of international economics are once again agape, and not in a flattering way, at the budget surpluses Germany’s government keeps running, when instead it should be stimulating the economy with tax cuts and higher spending. The surplus revealed this week for 2019, at 13.5 billion euros ($15 billion), is the fifth in a row, and the biggest ever.

Many Germans still regard such numbers as signs of economic virtue and virility, as they keep slashing public debt and reveling in high employment numbers. Alas, these positive indicators are likely to be lagging, not leading. That’s because an unusual era is drawing to an end, one that was likened by Bert Ruerup, one of Germany’s top economists, to a “second economic miracle.” (The first was West Germany’s long postwar rally).

In the past 15 years — somewhat coincidentally, the reign of Angela Merkel as chancellor — Germany turned from the “sick man of Europe” to the continent’s export powerhouse and growth engine. In the next 15 years, Germany won’t necessarily become sick again. But, as Ruerup puts it, it could simply turn economically “gray,” with meager growth indefinitely.

The miracle’s original causes included the labor and welfare reforms enacted by Merkel’s predecessor, Gerhard Schroeder, which put more pressure on jobless people to find work. They also included the simultaneous restraint shown by Germany’s labor unions in bargaining with employers, which reduced the country’s wage costs in international comparisons. If Germany had had its own currency, it would have appreciated; but with the euro, Germany in effect devalued.

This favored the flagship export sectors of “Made in Germany”: industrial chemicals, fancy machines and of course sleek cars. China binged on German stuff, as did much of the world.

Germany was thus a main beneficiary not only of Europe’s currency union but also of globalization. Among large industrialized economies, it’s the most open to the world. The sum of exports and imports has averaged almost 90% of Germany’s GDP during the past 25 years. By comparison, that ratio comes to only about 60% in the U.K. and France, 37% in China and 27% in the U.S.

But that same openness is now turning into a vulnerability as the era of globalization turns into one of protectionism and economic nationalism. Germany will suffer much more than other large economies from the present and coming trade wars, whether between the U.S. and the European Union or the U.S. and China. The emerging topography of new tariffs and other barriers is already causing companies to redesign their global supply chains, with many leaving Germany for other places, including the U.S.

Industries in particular turmoil, moreover, include those flagships: fancy cars and fancy machines. Both sectors are reducing their output. Even without more trade wars, Germany’s mechanical engineers, often family-owned Mittelstand firms that consider themselves “hidden champions,” are facing much tougher competition from Chinese rivals, which have improved their quality much faster than they’ve increased their costs.

The reputation of the car industry was already dented by its cheating on diesel-emission tests, first revealed in 2015 and a metaphor for Germany Inc.’s outdated bet on combustion engines and dirty fuels. For now, German carmakers and their component suppliers may still be profitable. But they’re entering an epochal transformation, possibly analogous to that in music from CDs to Spotify.

Expensive cars, owned and driven for fun by well-heeled types and powered by things that used to be plants millions of years ago, will gradually yield to electric vehicles driving themselves and shared by passengers who care more about the app and the price than the horsepower. The winners in this future industry aren’t clear yet. But the German auto giants will probably be “disrupted,” exactly in the way that the American academic Clay Christensen described long ago.

Even if the country’s car industry adjusts, it will employ far fewer workers. Electric motors have only about 200 parts to the roughly 1,200 of a combustion engine. New research by a German network of experts reckons Germany could lose 410,000 automotive jobs this decade.

The digital transformation also threatens the wider economy. Germany has been slow to adopt new workflows and business models. Ink signatures are still the norm. As of this month, German bakers have been told to print out little paper receipts for every loaf of bread they sell. (The reason is a new law meant to crack down on tax evasion, but the symbolism is devastating).

Meanwhile, the U.S. and China are racing each other to use, and dominate, artificial intelligence. Germany, paranoid about harvesting and processing AI’s vital resource, data, is a distant also-ran. According to a recent study, only one in four German firms is innovative enough to stay competitive. Worse, even those companies that want to innovate increasingly can’t find employees with the right skills.

That last problem, moreover, is only one side of perhaps the biggest cloud over Germany: a shrinking workforce and aging population. During the economic-miracle years, this dilemma still seemed abstract, thanks to the late effects of a postwar baby boom. Starting this decade, however, the problem will come out of hiding. Germany used to have (in 1990) about four people of working age for every pensioner. But now the boomers are starting to retire. By 2035, the Bundesbank reckons, only about two Germans of working age will support every pensioner. A gray economy indeed.

As old German strengths (in cars, say) become less relevant and hidden weaknesses (aging) come to the fore, Europe and the world should worry. The booming economy in the middle of the continent has long distorted the euro-area and global economies with the world’s largest current-account surplus. That won’t be an issue much longer. But the new troubles caused by a giant that starts ailing may be even bigger.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a member of Bloomberg's editorial board. He was previously editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.