Germany’s Coal Power Could Shut Down a Decade Early

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For a country that prides itself on its clean, green image, Germany’s power sector is remarkably dirty.

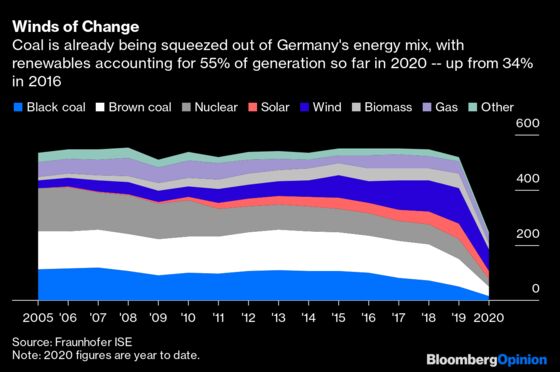

Despite having the third-largest installed base of wind and solar power after China and the U.S., Germany still relied on coal for 45% of its needs as recently as 2015. While the U.K. has been going without the fuel for months at a time, Germany’s legislation on retiring its coal fleets, which passed Friday, will keep plants switched on as late as 2038.

That “as late as” is key, though. Switching off the 40 gigawatts of coal power currently in operation is structured as a series of deadlines, rather than appointments — and there are strong incentives for generators to quit the market early. With benchmark prices for coal-fired power already in negative territory right now, don’t be surprised to see the entire industry shuttered by the middle of the decade.

To understand why, it’s worth considering that Germany’s main coal-fired utilities RWE AG, Uniper SE and Lausitz Energie Kraftwerk AG aren’t so much operators of industrial plants as commodity brokers trading the spread between processed and unprocessed products. Just as agricultural traders hope to make money on the crush spread between soybeans, soymeal and soya oil and refiners profit from the crack spread between crude, gasoline and diesel, coal-fired utilities trade the dark spread.

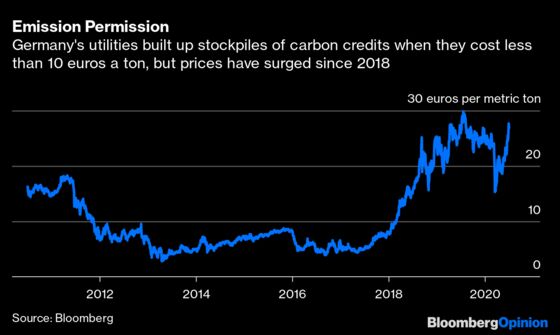

The dark spread represents the price of electricity in the forward market, minus the cost of coal and carbon credits, plus an adjustment for the efficiency of generators. It’s essentially the profit utilities can make on each megawatt hour. Thanks to the rise of European carbon prices in recent years, that number is already deep in negative territory.

That’s not quite as bad as it looks for Germany’s coal-burners. They tend to fix their prices years in advance, and still have substantial stockpiles of carbon credits bought years ago for about a fifth of what they cost right now.

Thanks to that aggressive hedging activity, RWE reckons it will reliably make between 26 euros and 32 euros ($29.30 and $36.06) a megawatt hour through 2023 on its coal and nuclear generation. With enough carbon credits to hedge its exposure out to 2030, it will still be able to at least break even and potentially make as much as 200 million euros a year even after earnings decline substantially from 2023 to 2025, according to a March presentation.

There’s an extra issue that needs to be factored in, though. Germany’s coal retirement plan will reward the generators that switch off early, with compensation payments starting at 165,000 per megawatt in initial auctions this year, declining to about half that amount in 2024.

With fuel and power hedges rolling off after 2023, and exposing the utilities to something much more like current dark spreads, generators will find themselves with a fleet of marginally profitable plants worth more as compensation cases than as functioning power stations.

The best hope for fossil-fired generators is that Germany’s mistaken decision to shut down nuclear power early, plus ongoing problems in getting permits to build onshore wind, lifts electricity prices enough to put dark spreads back in positive territory for a few more years. In the face of a market that had seen electricity demand stagnate for 15 years even before coronavirus hit, though, that’s a slim hope, and one likely to be rapidly snuffed as electricity imports from the rest of Europe rise.

The generation mix is already showing where things are headed. Without any closure plan or compensation payments, coal’s share so far this year has been less than 20%, compared with 43% as recently as 2016. Solar, a technology that was negligible a decade ago, last year contributed more electrons to the grid than black coal. Wind has overtaken brown coal, too.

Germany’s generators have spent most of the past few years negotiating with the government about the payouts they’ll receive in return for switching off their coal boilers. While doing that, they’ve got a strong incentive to make thermal power stations look as profitable as possible — but once the payouts have been written into law, there’s little incentive to keep running plants that barely cover their costs. Those stockpiles of carbon credits could even be sold at a profit to businesses with more of an incentive to use them.

It’s possible that Germany’s coal generators limp on for a period after 2025, mostly mothballed, available as occasional back-up that can be switched on in winter or on calm cloudy days when other technologies fall short. What matters for the global climate isn’t the technical capacity of grid-connected thermal power stations, though, but the tonnage of coal they burn and the carbon dioxide that emits. It’s not Germany’s retirement plan killing that off. With a price on carbon, renewables are simply out-competing coal on the open market.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.