(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Now that Germany has dodged a recession, political decisions on fiscal stimulus have been postponed. Yet the country’s employers and labor unions are still demanding an infrastructure investment program worth at least 450 billion euros ($498 billion) over 10 years, not to give an immediate boost to growth but to keep the country competitive in the future.

The 450 billion euro figure comes from a new report jointly drafted by the German Economic Institute in Cologne, which is close to two big employers’ lobby groups, and the Macroeconomic Policy Institute, part of a labor union-linked foundation. Presenting the study on Monday, Dieter Kempf, president of the Federation of German Industries, the country’s main industrial lobby, said Germany had turned into “snoreland” in a stupor of self-satisfaction; it’s time to wake up.

The World Economic Forum ranks Germany as the world’s seventh-most-competitive economy this year, down from third in 2018. According to WEF, its greatest weakness is in information and communication technology adoption, where it’s ranked 36th in the world; only one German out of 100 has a fiber optic broadband subscription, compared with one out of 32 in South Korea.

In an embarrassing episode on Monday, a state TV broadcast about a special government session on improving mobile coverage was broken off because of a bad connection.

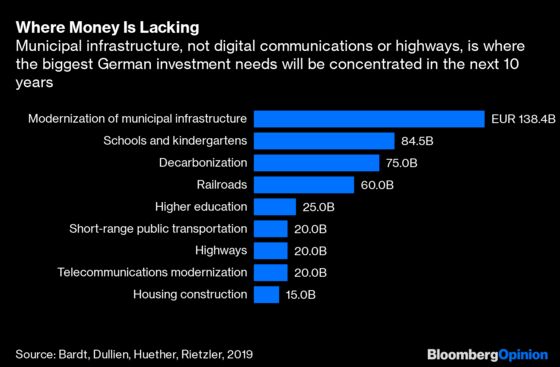

But, surprisingly for outsiders, the authors of the report suggest only that the government spend about 20 billion euros over the next decade on improving the telecommunications infrastructure, mainly to plug coverage holes where private investment can’t pay off. The rest of the money is needed elsewhere.

The WEF describes physical infrastructure as one of Germany’s strengths, but Germans love to complain about it, mentioning, for example, that the average age of railroad bridges in their country is 60 years and that some 10,000 of them were built before World War I. Yet it’s not roads and public transport that require the most investment, either: The two institutes put those needs at 100 billion euros between 2020 and 2030.

The biggest single investment need comes from Germany’s municipalities. As the federal government and the states have consolidated their finances under Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government, introducing debt brakes and deficit-free budgets, not enough money has trickled down to the local level. Even though the federal government has recognized the problem and taken over the full funding of some social programs, such as old-age pensions and unemployment insurance, municipalities’ current social obligations have been increasing, forcing them to put off investment in the maintenance of schools, streets and water-supply systems. They — especially the industrial towns that lost out from globalization — built up a combined investment gap of 138.4 billion euros, according to a nationwide survey of communities cited in the two institutes’ report.

Even when the money is there in town and district budgets, many municipalities don’t have the staff and expertise to plan investment projects properly, and businesses that could take on the jobs have been wary of expanding lest municipal orders be cut back again. A big federal program to close the investment gap would fix that.

Germany isn’t exactly in a state of disrepair. It doesn’t feel as though it is, even though potholed streets aren’t a rarity, trains often don’t run on time and cellular reception is spotty outside cities. Nor, however, does it feel future-proofed enough, even after a decade and a half of Merkel’s generally successful rule. The WEF touts unshakable financial stability (the country got 100 points out of 100 for it in the competitiveness ranking) as one of Germany’s biggest advantages, but that stability has been achieved, in part, by shifting problems to the local level.

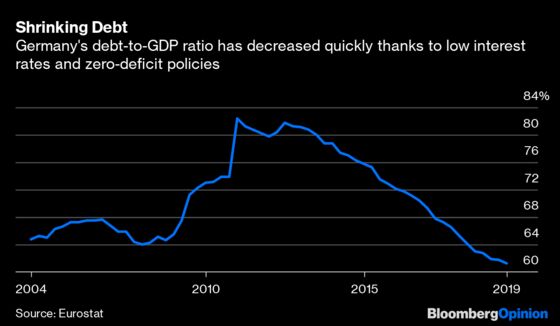

The authors of the institutes’ report point out that it’s not impossible to launch the investment program they propose even under Germany’s stringent debt-brake rule, enshrined in the constitution since 2009. The government, they suggest, could form a special foundation for the purpose. As long as it’s set up not as a funding vehicle for budgetary needs but as a structure tasked with specific new projects, its borrowing wouldn’t violate the constitutional restriction. Such borrowing, of course, would still count as government debt under European Union’s fiscal rules. But Germany likely still wouldn’t be in serious violation of them: Thanks to negative interest rates, the country’s debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio is expected to drop below 60% soon, which would allow Germany to run a bigger structural deficit than today.

The investment program proposed by the employers and the unions would cost about 1.3% of GDP a year at today’s economic output level. That’s not an impossible price for future-proofing while the interest rates are extremely favorable. If Merkel wants her Christian Democratic Union to win the 2021 election, and if Finance Minister Olaf Scholz wants his Social Democratic Party to have a fighting chance, both should give the proposal serious consideration: Voters may want to rise and shine from snoreland.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.