Can NATO and Europe Count on Germany Against Russia?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s difficult not to write satire, observed Juvenal, one of the art’s greatest practitioners. If he were alive today to parody German foreign policy instead of Roman imperial politics, he might sound like Marcel Dirsus, a scholar at Kiel University.

This week, Germany’s new foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock, was in Kyiv and Moscow, trying to talk Russia out of attacking Ukraine. Before she left, her government had, of course, consulted with Germany’s allies in NATO and the European Union. Here, via Dirsus, is how that dialogue could have gone:

Germany: “We need to defend the liberal international order. Human rights!”

Allies: “I’m with you! Russia is redrawing borders in Europe by force. Could you deliver weapons to Ukraine or maybe train their military if Russia keeps threatening them?”

Germany: “You know I’d love to, but because of history we have a complicated relationship to the military so we can’t do it. You get that, right? Happy to help in any other way, though.”

Allies: “Yeah, I get it. Okay, so would you be willing to, I don’t know, not build that pipeline with Russia while [Russian President Vladimir] Putin is holding a gun to Kyiv’s head?”

Germany: “That definitely won’t work for me because of reasons. Dialogue and stuff.”

Allies: “Okay, could you at least tell Putin that you’ll cancel Nord Stream 2 if he attacks? That could make a difference.”

Germany: “I could do that, but I don’t want to, so I won’t. If you really think about it, a pipeline that helps Putin while hurting Ukraine really isn’t linked to Putin or Ukraine. Best I can offer are vague speeches calling on both sides to de-escalate. As you know, the most important thing to us are human rights and the liberal international order. We love dialogue. Dialogue is the best!”

Like all good fiction, this exchange is the closest you can come to truth. Allies, led by the U.S., have for decades been frustrated by Germany’s habit of ducking its responsibilities. Some even wonder whether Germany would be a reliable partner if push ever came to shove — if Russia or China, say, tore up whatever’s left of that ballyhooed liberal international order and went to war.

One expression of Germany’s longstanding ambivalence is its notorious refusal to acknowledge that hard power is a legitimate and necessary instrument in the toolkit of diplomacy. This mentality originated in atonement for the Nazi past. But it’s long since become a convenient excuse to skimp on military spending and hang back when the alliance needs to send troops into harm’s way.

Mixed into this faux-pacifism is a bizarre strain of Russophilia, usually accompanied by thinly disguised anti-Americanism. This phenomenon is strongest at the political extremes — within the populist Alternative for Germany on the far right and the post-communist Left Party. Both are disproportionately popular in the former East Germany.

But Russophilia is also widespread among the center-left Social Democrats, which now run the government under Chancellor Olaf Scholz. In their mythology, the Cold War was won not because the West stared down an “evil empire,” but because German Social Democrats initiated rapprochement with the communist bloc, meaning Moscow. Their mantra: Talk to the Russians long enough, and everything will be fine.

Something curious happened to this Ostpolitik (“Eastern Policy”), as it’s called. Somehow the Germans who invoke it today mean accommodating only Russia. At the same time they have a tin ear to the anxieties of all their other partners in Eastern Europe, who have historical traumas about both the Germans and the Russians. These include the Ukrainians and EU members such as Poland and the Baltic states.

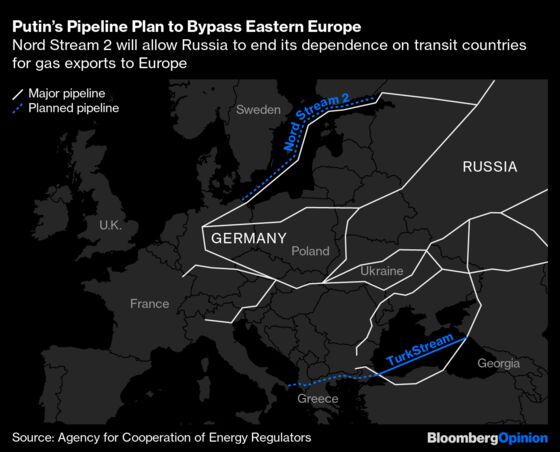

Deaf to their concerns, Germany — at the prodding of Social Democrats — agreed to build a gas pipeline under the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany. Almost as one, the allies pointed out that this link — Nord Stream 2 — is a geopolitical project by Putin to allow him to cut off the gas flowing to western Europe through Ukraine, Poland and other countries.

In reply, successive German governments, including Scholz’s, keep intoning that the pipeline — which is still waiting for regulatory approval — is a private business deal that has nothing to do with Putin’s other designs. That’s why Dirsus’ satire above is so biting.

Foreign Minister Baerbock bears no blame for any of this. She’s a co-leader of the Greens, one of the junior partners in Scholz’s government. Her party has in recent years edged away from its traditional anti-Americanism and become more Atlanticist. During last year’s election campaign, she called out both Russia and China for their aggression and demanded that Germany side firmly with the West. She also wants Nord Stream 2 stopped.

But now her Greens are members of Scholz’s government and must keep the peace. How Germany would respond to a renewed Russian invasion of Ukraine is, therefore, unclear. The West has promised to answer with sanctions. Of these, one of the toughest would be nixing Nord Stream 2. But to take that step, the Greens and the third coalition partner, the Free Democrats, would have to prevail over the Social Democrats.

How Germany’s governing coalition overcomes this rift may determine whether the West will indeed speak as one against Putin’s coming provocations or attacks. Allies should pay close attention. Nobody anywhere is suggesting that “talking” or “dialogue” should ever cease. But the Germans must accept that there are times in history when jaw-jaw alone won’t do — because what’s required is action.

More From This Writer and Others at Bloomberg Opinion:

-

Could Putin De-Escalate Even If He Wanted To?: Andreas Kluth

-

Russia’s Winter Generals Have Yet to Show Up at the Gas War: Javier Blas

-

Putin Is Only Pretending to Be Crazy on Ukraine: Eli Lake

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. He was previously editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist. He's the author of "Hannibal and Me."

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.