Germany's Inconvenient Truth? It's Too Complicated

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Can an economy exhaust itself? And what happens when a strategy that works well for decades finally meets the end of the road?

Harvard Kennedy School’s Atlas of Economic Complexity, an immense academic project aimed at understanding how and why countries develop, has some answers, and they are worrying. The Atlas, revised last month, crunches export data from the United Nations for every country on earth to produce minutely detailed accounts of what each country makes, and how it has developed. It is available free on the web, in a plethora of beautiful data visualizations, which entrepreneurs, economists, investors and finance ministers can all mine for ideas.

The latest edition shows investors the neglected countries that could use capital. But the most interesting, and unsettling, finding is about Germany.

Once the engine room of Europe, Germany is now established as the problem child of the global economy. Purchasing manager surveys show that its manufacturing sector is in recession and by far the weakest in the western world; industrial production is falling; its banking system is stricken; and its negative interest rates are warping markets across the globe. For seven years now, German rates have been lower even than those of Japan, previously the byword for economic malaise and deflation.

Outside the country, frustration is growing. President Donald Trump is angry that its low rates made the dollar uncompetitive, while many call for Germany — which has dutifully applied austerity ever since the crisis — to reverse course and administer a fiscal boost that could jump-start the rest of Europe.

The Atlas, however, suggests that Germany’s deep-rooted problem needs more than a splurge of government spending. It has run out of natural ways to grow. After decades of expanding steadily and methodically from one product to another, and training its workforce to adapt their skills to new sectors, there is little or nothing left for them to do. This conclusion comes from the Atlas’s model for how countries can grow, which depends on two variables: connectedness and complexity.

The Harvard team shows which products and technologies naturally align with others, or in their words are most “connected.” A country wants to make “connected” products, because their expertise and facilities can be readily transferred to something else. For example, it isn’t hard to move from making car components to making full cars. Countries with unconnected industries, like mining, find it harder to diversify.

A country should also move into more “complex” products, which have greater productivity, build greater competitive advantage, and can create more wealth. As countries develop more sophisticated industries, they grow wealthier. Germany has done this for many decades, and done it better than anyone else. And that is its problem.

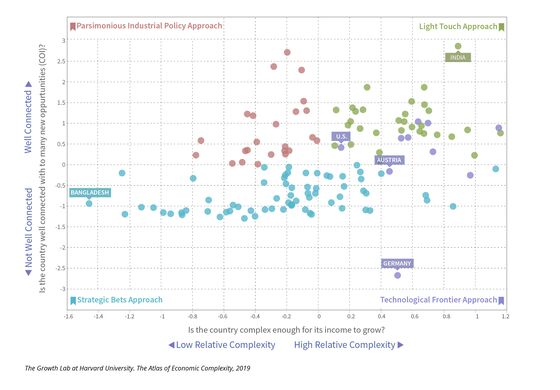

Harvard’s research is summed up in the above visualization, in which each dot is a country. The horizontal axis measures the relative complexity of each country – the further to the right, the more complex. Bangladesh, on the far left, ranks as the least complex on this scale, giving it great room to expand. Germany is one of the most complex.

On the vertical scale is “connectedness.” As Tim Cheston of the Kennedy School says, “We’re fundamentally saying, how easy is it to jump from where you are now to new opportunities?” India, with a large and growing educated workforce but not a great and powerful industry as yet, has great opportunities to expand. Germany, on the other hand, has a harder job finding new products and industries to move into than any other country on earth. Far out at the bottom right corner, it is the obvious outlier.

By contrast its neighbor Austria, also highly developed with a sophisticated industrial sector, hasn’t yet explored all the opportunities open to it. So it has further to develop just by natural diversification.

“Germany has basically exploited all of its high value opportunities. But while it’s well-connected there are no opportunities to improve diversity. So it will need to produce wholly new global products,” says Cheston. “It has to look for something and hope it finds something.”

The colors of the dots refer to the strategy that the Harvard team recommends for each country . Pale blue is for “strategic bets” — underdeveloped countries need to decide on industries they want to develop, and go for it. The green dots are well-connected countries that can adopt a “light touch” and allow their industries to develop, while the red dots are under-developed but well connected countries that need a parsimonious industrial policy to address bottlenecks and move to similar products.

The fewest dots are purple. These are countries that have reached the “technological frontier.” For them, “having exploited virtually all major existing products, gains come from developing new products”.

They must advance by innovation, not adaptation. After decades of inching from one product to a slightly more advanced one, Germany must now find wholly new products. That means sinking a fortune into research and development, and hoping that German scientists come up with transformative products that nobody knows they need. It needs to find a Walkman or an iPod.

German companies already invest heavily in R&D, and their government could join them with more spending. But while this is a necessary condition for growth, it is not a sufficient one. Germany has to find something new that doesn’t yet exist, and which it cannot yet make.

Until a German iPod comes along, stalled German manufacturing looks to be a fact of life. And that’s a problem for everyone else.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.