(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Aviation has long been considered General Electric Co.’s crown jewel, but with the company’s free cash flow turning negative this year, “crown jewel” is a relative term and the business is coming under increasing scrutiny. Some of it is deserved; some isn’t.

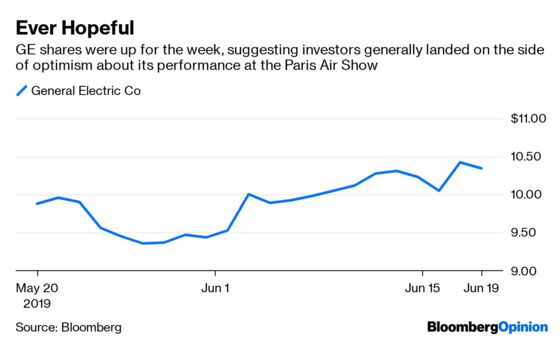

GE Aviation CEO David Joyce seemed to be on a mission at this year’s Paris Air Show to prove his division’s worth. He arrived armed with more financial detail than GE had ever previously provided for the business, came out swinging against suggestions he was sacrificing price to score revenue wins, and announced some notable orders. And yet questions remain about what the business’s true financial profile would be if it was reconstituted as a stand-alone company and cut off from the tax and working-capital benefits that have historically come with being part of the mother ship. That matters, because many investors continue to value GE based on the sum of its parts, the argument being that the aviation unit alone can offset trouble spots in GE’s power, renewables and long-term care insurance operations and support a higher valuation for the stock.

First, the positives: GE Aviation and its CFM International engine joint venture with Safran SA booked $55 billion in orders for engines and services at the Air Show, exceeding the $35 billion target Joyce laid out at a media briefing at the start of this week. Like most order tallies from the event, not all of that is technically new business. The number includes an order from AirAsia that had initially been announced in 2016 and entails 200 of GE’s LEAP engines. The purchase was finalized at this year’s event and AirAsia also expanded a servicing agreement, bringing the total value of the deal to $23.1 billion before customary discounts. But there was also a significant new win: Indian budget carrier IndiGo agreed to a $20 billion order for Leap engines, spares and overhaul support.

The deal is a blow to United Technologies Corp.’s Pratt & Whitney arm, which had been the sole provider of engines for IndiGo’s Airbus SE A320neo jets. As with Boeing Co.’s face-saving win of an order for its embattled 737 Max jet, some analysts have wondered what GE had to give up in order to convince IndiGo to abandon Pratt. They were encouraged in this thinking by comments from Pratt President Bob Leduc, who said “GE was willing to be more aggressive than we were” on pricing. That may just be Leduc talking his book, though. Unlike in the depressed gas turbine market, where every revenue win likely comes at a cost to GE’s margins, GE shouldn’t need to sacrifice profit to chase market share in aviation – both in general and in the case of this particular deal. Pratt’s GTF engine has had a series of glitches that ultimately proved fixable and relatively minor, but as one of the largest buyers, IndiGo has borne the brunt of the fallout, including in-flight engine shutdowns and grounded planes. Earlier this year, India mandated weekly inspections of certain engine parts and restricted some operations for Airbus planes powered by the GTF.

GE has engine headaches of its own. Boeing’s CFO Greg Smith put GE on the hot seat earlier this month, saying its GE9X engine was holding up the aerospace giant’s new 777X plane. At a media briefing this week, Joyce said GE discovered a part of the engine was showing more wear than anticipated and because of the extensive testing required to prove it had fixed the issue, the 777X’s first flight likely won’t happen until the fall. Investors are understandably jittery over any product setbacks after the uncovering of durability issues with GE’s flagship H-class gas turbine. But given the GTF’s history of bugs, I find it hard to fault GE for making tweaks to its engine. In the wake of the voluminous criticism directed at Boeing and the FAA for not realizing the potential impact of a software system linked to the Max’s two fatal crashes, rigorous testing – before the planes start flying – would seem to be in everyone’s best interest.

GE has argued it has a technology advantage that will continue to give it an edge even as United Technologies increases its R&D budget through a blockbuster merger with defense contractor Raytheon Co. That remains to be seen, and I don’t think GE’s order wins at the Air Show tilt the scale one way or another. A smart R&D budget is worth more than a big one, but United Technologies will have a lot of money to work with and that will make it difficult for GE and others to stand pat. GE Aviation’s ability to respond to that competition ultimately boils down to how much cash flow it generates – and that’s where confusion continues to reign supreme.

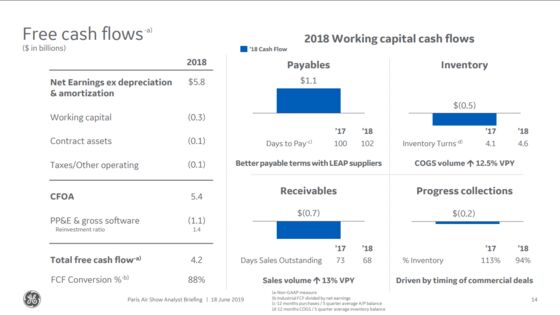

At Tuesday’s analyst event, Joyce laid out the various inputs behind the unit’s reported $4.2 billion in free cash flow last year. It was a sign the company is taking investors’ demands for more transparency seriously, although it remains disappointing that these disclosures come in fits and starts. There were some positive takeaways: Citigroup Inc. analyst Andrew Kaplowitz noted the improvement in inventory turns in 2018 even as GE ramped up production of the Leap. But one sticking point was the allocation of corporate costs including pension, interest and taxes, with JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Steve Tusa and Gordon Haskett’s John Inch debating whether the unit was carrying its fair share.

On the subject of taxes, GE didn't do itself any favors as far as illuminating what's really happening in the aviation unit. The presentation included a line that indicated taxes and other operating expenses deducted $100 million from the aviation unit’s cash flow, which seems quite low on the face of it. But the aviation unit actually pays more than that in taxes. And GE isn't hiding that burden from its calculation of the free cash flow. You just have to know where to look for it.

The starting point for GE’s explanation of how it calculated the aviation unit’s free cash flow – $5.8 billion in net earnings after adjusting for depreciation and amortization – had already been adjusted for taxes accrued, based on its operations, according to a company representative. GE confirmed the aviation unit pays a tax rate in the low 20% range that CFO Jamie Miller has guided to for the entire company. The $100 million number for taxes and other operating expenses in the Air Show presentation is something different. That is the difference between taxes paid and accruals in 2018. Are you still with me?

The fact that this is all so confusing underscores one of the issues I’ve had with GE’s efforts to be more transparent. Disclosures come in fitfully and often leave people with only more questions. I don’t think GE always does this on purpose; it’s partly a reflection of the fact that this remains an incredibly complex company and any given number is going to require a half-hour explanation. But you can’t have it both ways. Is GE Aviation a crown jewel? Yes. Is GE very good at explaining that? It could use some work in that department.

The total doesn't include engines for the 200 737 Max jets that British Airways owner IAG SA ordered at the Air Show. CFM is the sole engine provider for that plane.The list price for those engines is $5.8 billion.

The flip side of Leduc's comments was Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc CEO Warren East's description of GE as a "very savvy commercial operator."

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.