(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When it comes to battling climate change, President Joe Biden is a man in a hurry. As he should be. Democrats cling to a Senate majority by Vice President Kamala Harris’s fingertips, and midterms are just 21 months away.

Biden made no secret of his green ambitions when campaigning. Still, his flurry of executive orders took the energy industry aback. Some of that was just the usual Pavlovian response to any mention of regulation. The Keystone XL pipeline expansion, for example, was on life support anyway, and the plug was all but pulled the day Biden won. But his other actions, such as the temporary suspension of permitting and the longer suspension of leasing for drilling on federal lands, were quicker and broader than anticipated.

Taken together, Biden’s orders look a lot like a frontal assault on star-spangled hydrocarbons. In this, he runs the risk of having any increase in energy prices tied like an anchor to his presidency, as has happened before.

This time, however, the White House may feel it has some breathing room.

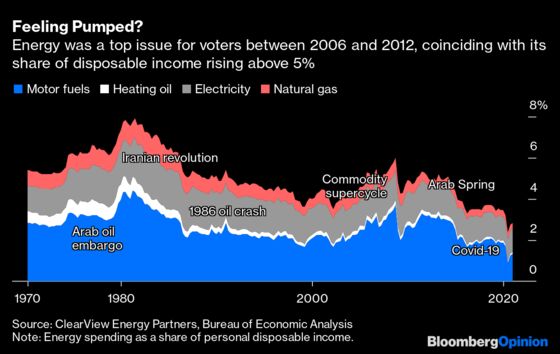

Clearview Energy Partners, a Washington-based research firm, tracks the share of your wallet taken by energy expenses as part of its annual (and highly recommended) “Energy Policy by the Numbers” analysis. There’s no hard and fast rule on when the irritation of energy costs tips into being an outright, and politically troublesome, burden. But looking at the chart below, you can see one explanation as to why energy ranked highly on the Pew Research Center’s polling of election issues between 2006 and 2012 but dropped off after that.

The energy transition has an unavoidable impediment: It requires upfront costs ahead of longer-term benefits. As a rule, we like our outlays minimal and gratification swift. One particular risk Biden faces is that curbing fossil fuel supply tends to work faster than, say, switching the federal vehicle fleet to plug-ins. He is therefore vulnerable to attacks about raising the retail cost of energy in the short term without much to show for it yet.

Look back at that chart, and it’s easy to see pump prices are the biggest swing factor. A combination of regulatory constraints on supply with economic recovery on the back of vaccination and stimulus checks could accelerate the recent upswing in the oil market. And as former President Donald Trump could tell you, rising gasoline prices aren’t what you want heading into midterms.

Yet the sheer damage done to U.S. energy demand by Covid-19 creates some room on this front, particularly in the context of perhaps massive recovery and stimulus packages.

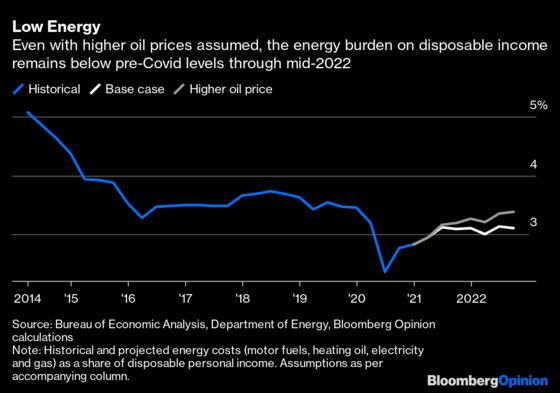

In the chart below, I’ve taken the energy consumption and pricing forecasts and personal income assumptions from the Department of Energy’s short-term outlook and used those to project the energy burden on incomes through the fall of 2022 — both under the DoE’s base case and assuming higher oil prices .

There’s much in this projection with which to take issue; obviously fuel prices and income dynamics are linked. Still, in the current economic context, higher oil prices are likely to be partly a function of a stronger recovery, which should also raise disposable income. That should hold the other way, too.

Constraints on oil drilling aren’t likely to curtail supply too much in the near term (certainly not relative to existing headwinds). The impact of Biden’s leasing moratorium is more of a post-2024 thing. Besides, if oil prices did rise sustainably above $60 a barrel (or especially $70) over the next year or two, frackers would somehow get more barrels flowing; production is already up by more than a million barrels a day since last May’s collapse.

The bigger issue is demand. The Energy Information Administration’s long-term outlook, released last week, projects U.S. drivers will never again burn as much gasoline as they did in 2019 — even under a high economic growth case. This represents a mix of pandemic-related changes to behavior, rising fuel efficiency and increasing market share for electric vehicles.

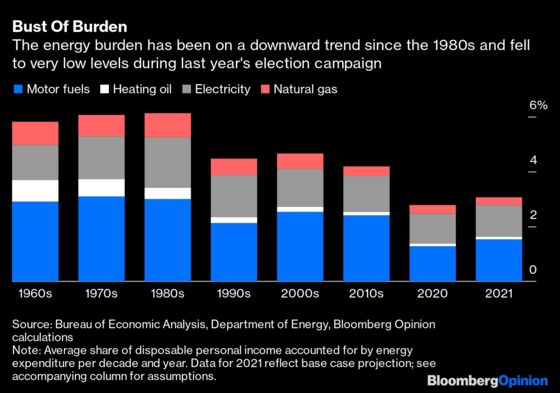

These structural changes are important, even if they play out over time. The downward trend in energy costs in the 2010s owed much to fracking; even if investors didn’t always reap the profits of that boom, consumers did (as long as we aren’t pricing in climate change, anyway). What’s different now is that even though fracking won’t get back to those glory days — which has more to do with investors’ exit than Biden’s entrance — its capacity to still grow will tend to cap oil rallies. And so will shifts in demand patterns.

Suppressed demand provides a window during which Biden may feel more confident in moving quickly on climate measures with less risk of a backlash. Indeed, as ClearView’s analysts write, the longer-term trend of energy costs falling as a share of income “might explain why Biden could campaign on the most aggressive climate platform in Presidential history without alarming lower-income voters in the Democratic Party base.”

There are risks to all this, of course. Averages mask big disparities in earning power and driving needs; rural voters tend to be more exposed on both counts. Oil prices can spike for any number of reasons way beyond the control of the White House. And $3 gasoline, even if it doesn’t take quite as big a bite of disposable income as it used to, has an unhelpfully totemic quality.

Against that, if oil demand strengthens because of stimulus dollars, that may shield Biden from some of the political flack. Either way, a lower energy burden offers fuel for his climate ambitions. Tomorrow’s column will look at what else is driving him.

I multiply the DoE's projections of gasoline, distillate and heating oil consumption by projected retail prices as a proxy for personal spending on motor fuels and heating oil. I then use the rate of change in those figures to project the Bureau of Economic Analysis' expenditure data forward. For electricity and gas, I use the DoE's demand forecasts to project expenditure, with positive adjustments of 1% in 2021 and 2% in 2022 to reflect price increases in residential bills. For disposable personal income, I adjust the DoE's real figuresfor inflation.For the "higher oil price" case, I add $5 to the DoE's "refiner average acquisition cost" in 2Q2021, $10 in 3Q2021, $15 in 4Q2021, $20 through the first half of 2022and $25 in 3Q2022. Cracking and retail margins and fuel taxes are as per DoE projections. These calculations imply the average crude oil price rising from about $52 in 1Q2021 to about $74 by 2Q2022, and retail gasoline from $2.33 a gallon to just under $3.40.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.