$3 a Gallon! Who Can Do Something About Gas Prices?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- With warnings against overseas travel firmly in place, that summer road trip is looking more attractive. It’s also looking more expensive. Perhaps the U.S. government should look at what China is doing to ease rising oil prices and sell off some of its strategic stockpile.

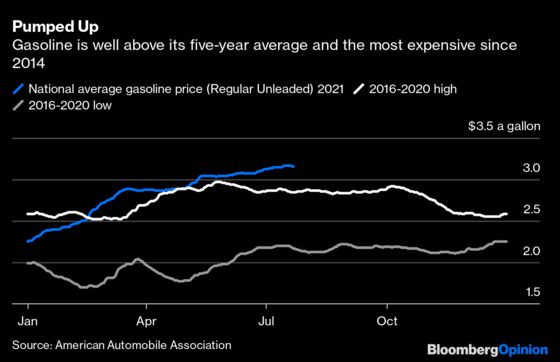

U.S. gasoline prices at the pump have been firmly above $3 a gallon on average since mid-May and show no sign of coming down any time soon.

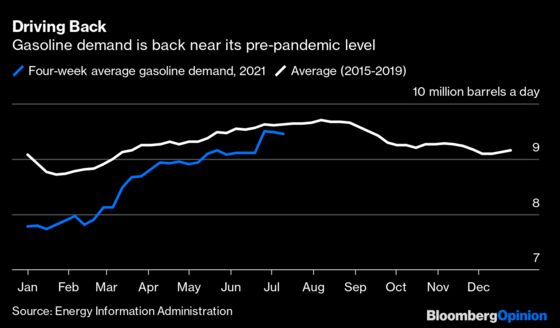

That’s putting pressure on American drivers, who are back on the road using almost as much fuel as in the five years before pandemic lockdowns kept everyone home.

While gasoline prices don’t follow the crude market in lockstep, the two are very closely linked, particularly in a country like the U.S. that doesn’t have the large, fixed taxes on road fuels that we “enjoy” in Europe. Crude prices have risen nearly 60% this year, with benchmark West Texas Intermediate hitting its highest level since 2014 and getting within a whisker of $77 a barrel.

Who can come to the rescue of the American consumer? U.S. oil companies certainly won’t. Domestic production peaked in November 2019, months before the coronavirus hit. The “Drill, Baby, Drill” mantra was replaced by a newfound belief in the primacy of profit over production growth. As a result, companies operating in the shale patch — at least those in public ownership, which account for most of the output — aren’t going to embark on another pumping surge anytime soon.

Foreign suppliers aren’t stepping up either. The producing countries of the OPEC+ alliance have patched up their differences, ending two weeks during which there was a real chance their pandemic deal could fall apart and trigger a production free-for-all like the one we saw in April 2020.

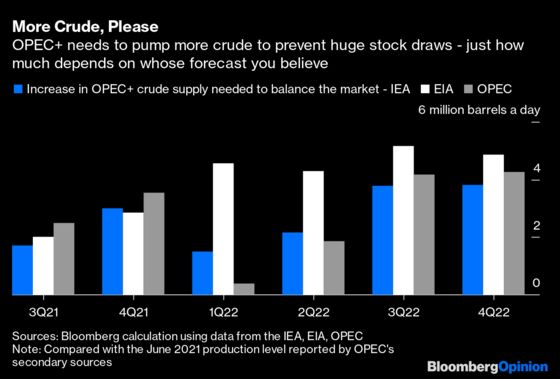

OPEC+ agreed to increase output by 400,000 barrels a day every month until they’ve put back all the crude they took off the market in May 2020, a process that will last through to September 2022 and could be extended. That falls far short of what the world’s leading oil-forecasting agencies say is needed to balance the market in the coming months, although there are differences of opinion over just how much is required.

But one thing they all agree on is that the world pretty much needs OPEC+ to increase production by about 2 million barrels a day on average this quarter from the group’s June production level and by another 1 million barrels a day in the final quarter of the year. Last weekend’s deal has them adding at most 1.3 million this quarter and then another 600,000 barrels on average in the fourth.

They’re unlikely to open the taps more than planned for the rest of this year, despite pleas from some of their biggest customers. No one’s in any rush to dampen oil prices.

Facing similar inflationary pressures as the rest of us, China this month sought to alleviate higher commodity prices by releasing inventory from its strategic stockpiles. The nation plans to supply about 22 million barrels of crude to major refineries, reducing their need for imported feedstock.

The jury’s out on whether this and other measures taken by Beijing, will work. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Citigroup Inc. think not, arguing that any attempt to stop the rally in commodity prices will fail in the face of supply constraints and buoyant demand globally, not just in China.

Yet even if any relief is only temporary, it could be worth the effort during the peak summer driving season. The U.S. government has the room, if not the will, to do something similar with its own oil stockpile, called the Strategic Petroleum Reserve or SPR. It’s far larger than it needs to be after the shale boom doubled production in a decade, even with last year’s collapse.

The SPR holds more than 620 million barrels of crude. With exports running at 3 million barrels a day so far this year, offsetting half of what’s bought abroad, it holds enough to meet more then 200 days’ worth of net imports. The International Energy Agency only requires member countries to hold 90 days’ worth in emergency stockpiles.

Using those reserves to ease price fluctuations has never been U.S. policy. But the country’s dependence on imported crude is very different than it was when the emergency stockpile was created. Maybe it’s time to start considering a new approach better suited to the times. The height of the summer driving season would be the perfect time to try.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.