Boris Johnson’s Next Big Make-or-Break Crisis Is Gas

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s not a good sign when government ministers shout on Twitter, “THERE IS NO FUEL SHORTAGE.” That’s like telling people “Do not imagine an elephant.”

In this case, not much is left to the imagination. The U.K. is panicking about fuel. Up to 90% of pumps in major British cities have reportedly run dry, and the British army is on standby to drive trucks to transport gas. The country’s competition law (which protects consumers from predatory high prices) has been suspended so that fuel deliveries can be coordinated to meet demand, and the government is in talks to keep the country’s second biggest oil refinery from collapse.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson is facing his biggest competence test since Brexit and Covid. Passing it will require more than the short-term fixes being mooted so far.

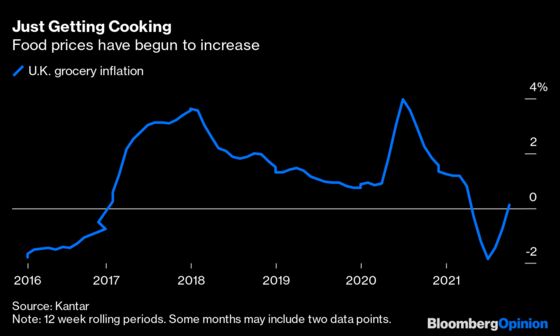

The fuel shortage is being driven largely by a shortage of large vehicle drivers. That and high gas prices are exacerbating other supply-chain problems and provoking nervous buying by consumers. This is already leading to higher food prices, a trend that is likely to continue in the run-up to Christmas. People are wondering when essentials will be in short supply. Cue a mini run on bottled water and other items.

Some public officials have blamed panicky consumers and industry associations for catastrophizing what they say is a temporary issue. But it’s never a good idea to blame the voter. Consumers are just being rational and businesses have been talking about labor shortages in the sector for some time.

Critics of the government have been quick to blame Brexit. That includes the man likely to replace Angela Merkel as the leader of Europe’s largest economy. “The free movement of labor is part of the European Union,” Olaf Scholz, the Social Democratic Party leader, said Monday. “We worked very hard to convince the British not to leave the union. Now they decided different and I hope they will manage the problems coming from that.”

Schadenfreude aside, Scholz exaggerates the Brexit effect in this case. Yes, splitting from the EU amplified supply chain problems. Delays at U.K. ports caused by Covid and Brexit regulations have reduced the number of drivers willing to come into the country. A week ago the U.K. government agreed to provide support for a private U.S. fertilizer company that is the largest supplier of carbon dioxide, in order to address a CO2 shortage. Northern Ireland, which is part of the EU’s single market for goods, is able to import CO2 from the EU more easily.

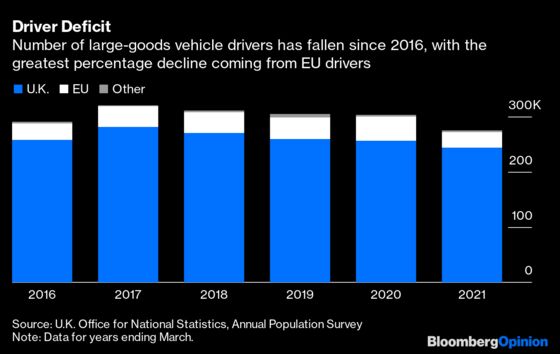

But skills shortages in transport have been a problem for a while. And although one culprit has indeed been declining net EU migration levels (and many drivers left the U.K. during Covid), there are also other big issues. Those include an aging workforce, low unemployment and difficulties attracting new candidates to a profession where the work is arduous and sometimes dangerous. The average age of a heavy goods vehicle driver is currently 55, with fewer than 1% under 25, says the main industry body.

Europe is also facing its own driver shortages. Data from 2020 showed that Germany was short 45,000 to 65,000 drivers and Poland was short 124,000 drivers. (The key difference with the U.K., though, is this hasn’t led to gas stations running out of fuel; Europe’s labor market mobility does help there.)

So far, the British government’s response to fuel shortages has consisted of denials and shortsighted fixes, and celebrating the wage hikes in the sector as a Brexit dividend. Wage increases may be welcome, but they are unlikely to be enough to replenish the supply of drivers. Plans to issue three-month visas for up to 5,000 EU drivers assumes people will actually want to return to poorer driving conditions for a short duration. That’s far from certain.

Other suggestions — such as relaxing test rules for drivers and extending driver hours — may replace one problem with another. Britain has among the toughest testing rules anywhere and that pays off in better road safety. Allowing drivers behind the wheel for 11 hours a day also sounds unsafe (a view insurers may take too). Though the Ministry of Defense is apparently helping to train more drivers, it will take some time before filling the gap.

There are no easy fixes, but the government needs to look at longer-term solutions. There have been calls in the past to expand training programs to include large vehicle drivers. The logistics industry has also asked to expand the National Skills Fund, an initiative to help adults retrain for new careers, to include heavy goods vehicles driver qualifications.

On top of these, the government could also, for a limited period, provide loans for driver training, which costs at least 4,000 pounds ($5,483), that are repayable out of income following employment.

There is certainly a need to make driving a more attractive career by improving facilities (as Europe has) and conditions for drivers. The government could also relax cabotage restrictions to increase efficiency and fuel savings. Of course, some of the raised costs for haulage companies will inevitably be passed on to consumers.

So far, the energy price surge and fuel crunch hasn’t seemed to impact the polls. With the Labour Party busy debating internal party rule changes, parsing leader Keir Starmer’s 12,000-word mission statement and arguing over the deputy leader’s colorful language in describing the government, Boris Johnson won’t be too worried yet.

But things could change fast. It was during the fuel shortages in 2000 that Tony Blair’s Labour government saw its popularity dip below the Conservatives’.

That crisis passed quickly. If this one drags out, the danger isn’t just that public opinion will sour. It could also undermine Johnson’s plans for rebalancing the economy and pushing for decarbonization — both of which will require more from taxpayers. Rather than downplaying the problem and blaming consumers, far better to face the elephant in the room.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.