(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In many ways, the business of selling Jif peanut butter, Crocs clogs and Whirlpool appliances could not be more different. But recently, these disparate consumer businesses have something in common: Each has benefited from the pricing power that a weird year of pandemic living has helped confer upon them.

J.M. Smucker Co., Jif’s corporate parent, said in its latest earnings report that raising prices and cutting promotions on this pantry staple added 5 percentage points to revenue growth at its U.S. consumer-foods division. Crocs Inc. — whose signature shoes fit squarely with the comfort trend that has taken over fashion — said in October that its average selling price had increased 8.8% from a year earlier to $21.36, partly reflecting a retreat from discounting. And Whirlpool Corp., maker of refrigerators and washing machines, said in January that its Ebit margin had widened in the latest quarter largely as a result of reducing promotions and “mix,” meaning customers were opting for pricey items as part of home renovation projects.

It is evidence of a unique feature of the pandemic economy: Rather than hunting for rock-bottom prices or staying on the spending sidelines, many shoppers are demonstrating a certain numbness to higher prices in a broad swath of categories. This behavior has turbocharged an already strong year for some consumer companies and cushioned its blow for others.

So far, overall inflation numbers have remained low, so the pricing tactics at these and other high-profile companies are not necessarily indicative of similar action across the consumer landscape. The latest U.S. government data released Wednesday showed consumer prices rose just 1.4 percent in January compared with a year earlier. But the more broadly price increases spread, the more the risk that they cause a surge in total inflation and raise concerns about an overheating economy that officials in Washington could seek to rein in. This bears watching.

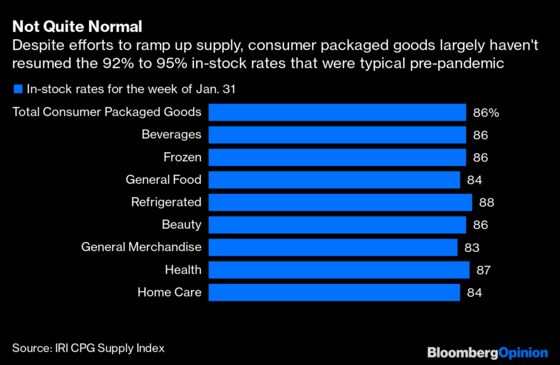

In the meantime, it’s easy to understand why consumers have been willing to pay higher prices on household essentials during these pandemic months. In-stock rates have remained below their pre-Covid normal in many categories. When shoppers are still facing a certain level of scarcity, it makes sense that many would resign themselves to paying more to get what they need. And with many consumers consolidating their spending into fewer store trips in an effort to adhere to social distancing guidelines, there fewer opportunities for them to make price comparisons.

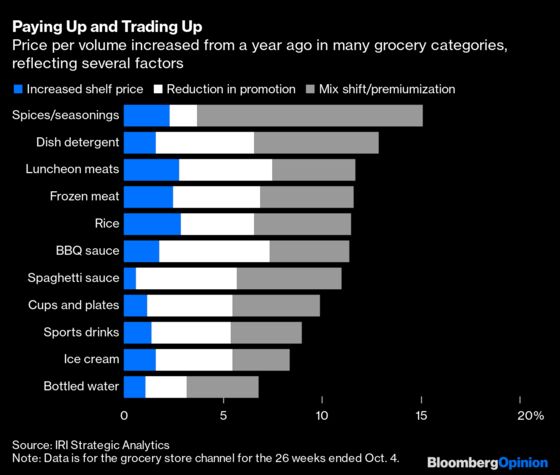

Pricing power has been particularly noticeable in the grocery business. Market research company IRI has found that while an increase in the number of items sold has been a key driver of sales growth in grocery, so, too, has the combination of higher shelf prices, fewer discounts and people trading up to fancier products. Procter & Gamble Co. reported in January that pricing factors contributed to sales growth in all of its major divisions in the latest quarter, including beauty and fabric care. At Mondelez International Inc., corporate parent of Oreo cookies and Ritz crackers, more than half of the fourth quarter’s organic sales growth was driven by price.

Beyond the grocery aisle, the consumer industry is generally benefiting from a shift in the experiences-versus-stuff dynamic. Because shoppers are not spending on travel, concert tickets, restaurant meals and the like, they’re likely to be sitting on a pile of savings. That, in turn, leaves them shrugging off mild price increases in other areas. This helps explain why a purveyor of durable goods, Whirlpool, was able to tighten the discounting spigot. Another seller of not-so-discretionary items, Tractor Supply Co., offered fewer promotions and markdowns in the fourth quarter amid strong demand for its gear.

While the apparel and accessories business generally had a devastating 2020, a silver lining has been the willingness of shoppers to pay full price. Mid-priced chains American Eagle Outfitters Inc. and Abercrombie & Fitch Inc. have recorded declining revenue but have bolstered gross margins with fewer promotions. Handbag heavyweights Michael Kors and Coach have also managed to sell more goods at full price recently. This seems logical: People who are springing for $300 leather goods right now don’t need to be baited with discounts. They’re collectors and true brand enthusiasts.

Will companies be able to stick to their pandemic-era pricing strategies when things start to return to normal? For the packaged-food companies, it is all but inevitable that they will have to rev up at least some promotions again at some point, perhaps later this year. When people can get back to store-hopping safely for the best deals, they will. When they can go back to restaurants instead of trying to re-create the gourmet experience at home, they probably won’t be shelling out as often for fancy cuts of meat. And they won’t have to settle for expensive organic milk just because it’s the only thing left in the dairy case.

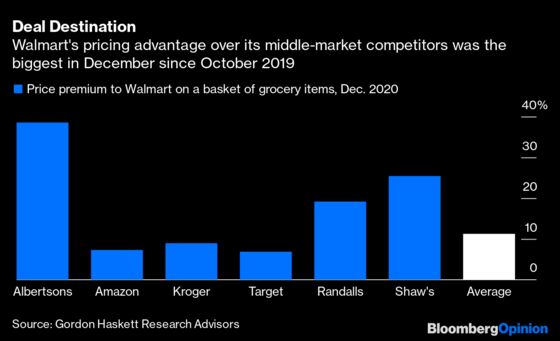

This should also shape retail watchers’ view of what the sales trajectories at major chains might look like as the public health crisis eases. UBS analyst Michael Lasser notes that Walmart Inc., with its longtime focus on everyday low prices, might not see its comparable sales downshift as much as traditional supermarkets because the latter likely got more aggressive with price increases during the pandemic that they will eventually have to walk back.

While the grocery business is destined to return to promotions, I don’t necessarily think other categories, especially apparel and accessories, should assume they’ll have go back to their discounting ways. Perhaps predictions of a second Roaring Twenties will materialize, with pent-up demand for fashion extravagance driving demand. Even if that doesn’t play out and shoppers don’t go wild rebuilding their wardrobes, mall retailers have become far too reliant on price enticements, rather than truly covetable clothes, to drive traffic. They are better off retraining shoppers to not wait around for discounts, even if that pursuit of more profitable sales costs them some customers.

The proliferation of pricing power among consumer companies reflects a quirky confluence of pandemic consumer psychology: a desperation to get the things we truly need, a surrender to expedience when so many aspects of day-to-day living require inconvenience, a nonchalance about little luxuries when the big ones are off limits. If broad-based inflation spikes later this year as some economists fear, that could scramble shopper behavior anew. Normal may be further off than we realize.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Sarah Halzack is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She was previously a national retail reporter for the Washington Post.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.