(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When it comes to retirement, France is like other countries, only more so: Everything about its system is untenable. It’s untenable that it has 42 separate public pension schemes — one for train drivers, another for opera singers, and so on. It’s untenable that the French think they have a God-given right to retire at 62 or even earlier. And it's untenable that they tend to riot in the streets every time the government tries to confront these realities.

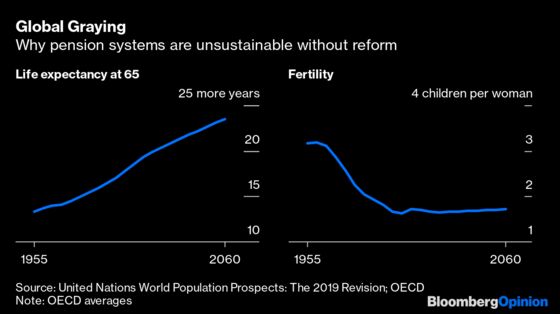

If they chose a slightly different perspective, the French might actually have reason to celebrate. After all, like people across almost the whole world, they can expect to live longer. The only problem is that unless they also work longer, this means they’ll need to draw their pensions for more years. Moreover, because of lower fertility in recent generations, fewer young people will be financing these pensions.

This global retirement crisis is a slow-ticking time bomb, not as dangerous as climate change but almost as consequential for financial markets, living standards and much else. This year, almost one in 10 people in the world will retire, according to the United Nations; by 2070, it’ll be about one in five.

The crisis isn’t evenly distributed. Africa, for once, has less of a problem, because of its relative youth. In North America, the problem is big. In Asia and Europe, it’s huge. The world’s “oldest” country (demographically) is Japan, and one of the fastest-aging is South Korea. The oldest continent is Europe, and countries such as Greece, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain are among those aging fastest.

Policymakers really only have three big dials to address this dilemma.

One is the contribution rate: how much people of working age are required to pay into the system. That rate is trending upward in rich countries. This represents an increasing burden on young people trying to get started in their careers (and questioning whether the system will even be around when they themselves retire). The alternative to making workers pay more is to fund shortfalls out of government coffers, which is a great plan to create the next sovereign-debt crisis.

The second policy dial is the replacement rate: the income level of retired people relative to what they made when they were still working. These rates range from as low as about 30% in Lithuania, Mexico or the U.K. to as high as 90% in Austria, Italy, Portugal or Turkey. Because most pension systems are unsustainable, these levels will go down almost everywhere. That means many old people will end up poor.

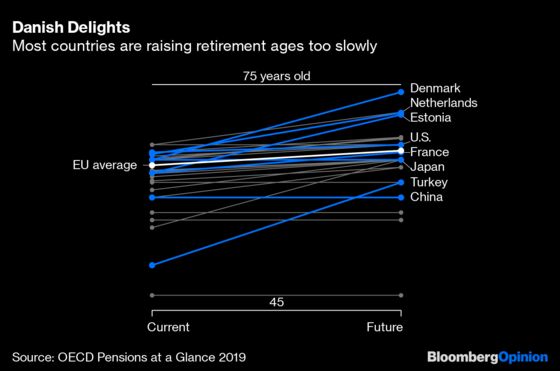

That leaves the third dial: the retirement age. Increasing it is the simplest way to make pension systems more sustainable, while simultaneously taking pressure off younger generations and promising more income to the old. What’s important is that the total time people spend in retirement doesn’t keep lengthening. That means the pension age should not only be raised immediately but also indexed to future gains in life expectancy.

Unfortunately, only one country, Estonia, has recently raised its retirement age. A few others, notably Denmark, have had good pension policies all along, so that their systems are in effect demography-proof.

By contrast, most other rich countries (defined here as the 36 members of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development) are headed for trouble. Only slightly more than half have legislated future increases in the pension age, and even those increases are adding only half as many years as life expectancy will rise by over the same period. In other words, they’re insufficient.

The reasons for this dynamic aren’t exactly mysterious. The effects of demographic change, like those of climate change, will be revealed gradually over decades. By contrast, a week is a long time in politics. Leaders who take a long view must sell their constituencies on changes that disrupt old habits and seem to bring nothing but inconvenience.

Voters tend to reward such honesty and foresight in their leaders by firing them or rioting. All the more reason for calmer minds to speak up and praise the courage of those politicians who dare to reform.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Timothy Lavin at tlavin1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a member of Bloomberg's editorial board. He was previously editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.