(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Corporate earnings are always important to stock investors, but they’re more important than usual now. If the U.S. stock market hopes to deliver a performance during the 2020s that remotely resembles its blockbuster 2010s, it will need a burst of earnings growth, and it won’t be easy.

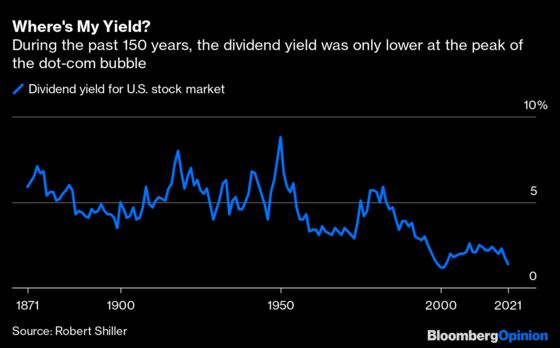

The reason everything hinges on earnings is because the other two sources of stock returns — dividends and valuation expansion — are unlikely to contribute much in the years ahead. The dividend yield on the S&P 500 Index is just 1.4%, the lowest in 150 years, excluding the peak of the dot-com bubble two decades ago. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 is more expensive than at any time except the dot-com era, and by some measures the priciest ever, so investors can’t reasonably expect valuations to expand much further.

Judging by the first quarter’s results so far, the market appears to be getting the help it needs from earnings. One reason, if not the chief reason, the stock market has soared since last spring is that investors are betting on a post-pandemic surge in corporate profits. With first-quarter earnings season well underway, companies have not disappointed — no small feat considering investors’ sky-high expectations. Wall Street analysts expected earnings for the S&P 500 to bounce 25% in the first quarter, the second highest one-quarter jump in analysts’ forecast on record. They were only slightly more enthusiastic about the first the quarter of 2010, when companies were digging out from the financial crisis.

But how the first quarter or even the rest of the year turns out is largely irrelevant for longer-term investors. The more important question is what earnings growth will look like further out. Investors were conditioned during the last decade to expect generous stock returns, but I suspect many of them did not realize that those returns were driven largely by a freakish surge in corporate profits. From 2010 to 2019, earnings for the S&P 500 grew 10.2% a year, the highest of any decade since at least the 1880s. That accounted for most of the S&P 500’s 13.3% annual return during the period. The other 3.1% a year came from dividends (2.3%) and modest valuation expansion (0.8%).

That kind of earnings growth is unlikely to continue. For one, there’s no precedent for sustained growth of that magnitude. S&P 500 earnings have grown on average about 4% a year since the 1870s and slightly more in recent decades, about 5% since 1990. Also, earnings grew about 10% a year in just two earlier decades, the 1940s and the 1970s, and both times the decade that followed was a lot more subdued. Earnings grew just 3.9% in the 1950s and 4.4% in the 1980s.

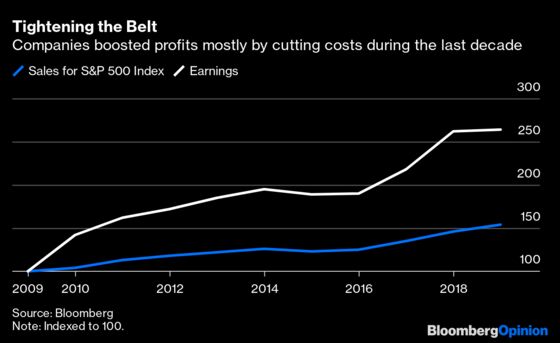

More problematic is that companies increased earnings during the past decade more by tightening their belts than expanding their businesses. Of the 10.2% a year in earnings growth, just 4.4% came from an increase in sales. The other 5.8% was mostly attributable to lower operating costs, interest expense and tax bills.

In other words, despite all the chatter about stakeholder capitalism from corporate executives, companies increased earnings during the last decade mostly by putting profits above all else. But with calls growing for the federal government to force companies to increase wages and pay more in taxes, they may no longer have that luxury. President Joe Biden’s infrastructure plan calls for higher corporate taxes. The administration is also widely expected to push for a higher federal minimum wage. And if interest rates creep up in the coming years, which they are likely to do as the economy returns to normal, the interest on companies’ debt will become a bigger burden.

Investors could get lucky, though. Earnings could grow in line with their recent average of 5% a year, dividends could kick in an additional 1.5% and valuations could hang around current levels for the remainder of the decade. That scenario adds up to an expected return from the S&P 500 of about 6.5% a year.

If that doesn’t sound lucky, consider an alternative scenario: Earnings growth comes in well below its historical average; discouraged investors decide stocks no longer warrant their lofty levels, causing valuations to deflate; and the dividend yield is boosted modestly by lower valuations but not nearly enough to compensate for anemic earnings growth and crumpling valuations. That’s what happened in the decade that followed the dot-com bust. From 2000 to 2009, earnings grew by just 0.6% a year, valuations contracted by 3% and dividends added 1.7%. The net result was a loss of about 1% a year for the S&P 500.

Yes, first-quarter earnings results are something to celebrate, particularly given that the pandemic is not yet over. But those results are unlikely to bear any resemblance to how companies will fare in the years ahead. For anyone planning to own U.S. stocks for more than a quarter or two, that’s the only thing that matters.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.