(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It can always get worse for FedEx Corp.

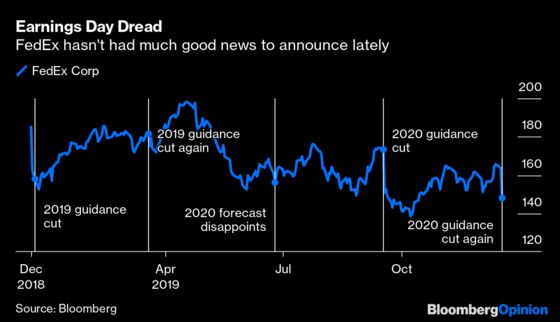

Back in June, I wrote that the parcel-delivery company had managed to fall out of a basement window when it issued fiscal 2020 guidance that fell well short of already depressed expectations. Two guidance cuts later, it seems we’ve sunk below the foundation and are in the dirt with the worms.

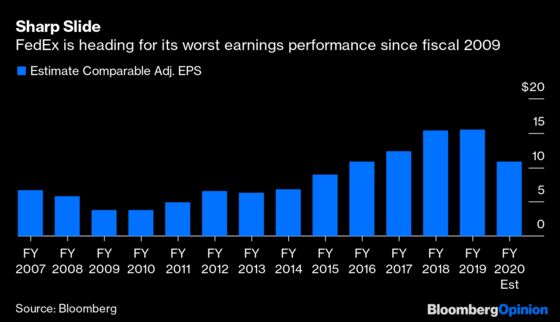

The latest of these misses came after the close of trading on Tuesday, when FedEx said it would earn no more than $11.50 a share in adjusted earnings and perhaps as little as $10.25. At the low end of the range, FedEx is facing an earnings slide nearly on par with what it experienced in 2009 amid the financial crisis. What’s worse is that its plan to fix this debacle rests largely on a “ just trust us” defense from a management team that continues to point the finger for its woes at a weak industrial economy and rising e-commerce costs — things that rivals United Parcel Service Inc. and DHL seem to have a much better handle on.

The current quarter could still bring more disappointments, with FedEx not calling for a significant rebound in slumping profit margins at its ground unit until the last three months of its fiscal year, which ends in May. But FedEx chief financial officer Alan Graf proclaimed that the company was “at the bottom and we’re going to come up off the mat.” He may be right.

Amazon.com Inc. stopped using FedEx to transport its own packages earlier this year and this week announced that it was banning the carrier from shuttling Prime packages for third-party merchants. While FedEx has said the impact to its revenue from the lost Amazon business is small, it’s still been a drag. The upside is that will make the comparisons easier in fiscal 2021. FedEx will also see the volume benefits from its rollout of seven-day delivery service, while a trade deal between the U.S. and China ( should one actually materialize) could boost the industrial sector and global economy. In the meantime, FedEx is reducing capacity at its Express air-delivery unit and plans to cut international and domestic flight hours by as much as 8%. It’s also planning a price increase on large packages in January and is trying to drive more volume from businesses, which tends to be more profitable than the e-commerce shipments it ferries to consumers’ doors.

But these feel like the sort of things that should have been announced more than a year ago and could have helped the company avoid some of its present pain. It’s not like FedEx’s challenges only recently sprung up, so it’s hard to fathom how the company could be caught so flat-footed by the November quarter’s disappointments. And FedEx only reluctantly took responsibility for the shortfalls. It fielded three questions from three different analysts on why there was such a giant miss on operating margins before CEO Fred Smith acknowledged on the earnings call that FedEx probably underestimated some of the cost of standing up the seven-day-a-week delivery service. It’s hard to think of a parallel example where management credibility is so low and management seems completely oblivious to that fact, although 3M Co. comes to mind.

For all this talk of a bottom, the real turnaround would likely come in fiscal 2022, when management says capital expenditures will decline significantly as it completes a replacement program for aging aircraft and at long last wraps up the costly and lengthy integration of its acquisition of European carrier TNT Express. The decline in spending will be a relief for investors who have been flummoxed by the lack of returns on the billions FedEx has spent upgrading its network over the past few years, but it still doesn’t answer the question of why that payoff has failed to materialize. One argument for FedEx’s severed relationship with Amazon is that as the e-commerce giant expanded its in-house logistics operations, it was only handing off the least profitable packages to third parties like FedEx. Troublingly, FedEx’s average yield in the ground business still declined by 0.1% in the fiscal second quarter even without the Amazon impact, while pricing power in the U.S. express business declined 0.3%.

The best-case scenario is that this isn’t a structural shift, but an execution issue. At a company that’s repeatedly struggled with execution over the past few years, that doesn’t inspire a lot of faith.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.