U.S. Banks Just Enjoyed Another Stress-Free Stress Test

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Federal Reserve’s stress tests are supposed to ensure that the U.S. financial system can survive a crisis, in part by requiring banks to build up loss-absorbing equity in good times so they’ll be ready when the bad times arrive.

Judging from the latest results, they’re not up to the task.

By all indications, now would be an excellent time for banks to be augmenting their defenses. They’re generating record profits. The economic expansion is close to becoming the longest in U.S. history. And various developments -- including excesses in corporate lending and President Donald Trump’s erratic trade policy -- suggest that trouble might not be far away.

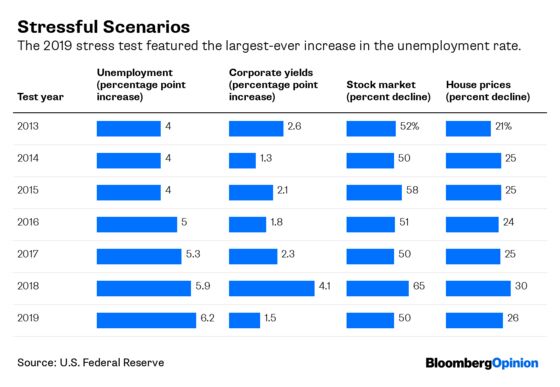

To nudge banks in the right direction, the tests should be getting more stressful. So are they? On the surface, they might seem to be: Over the years, the hypothetical economic slumps and market routs that they impose upon the banks have tended to get harsher. The Fed eased off a bit this year, but its severely adverse scenario still featured the largest-ever increase in the unemployment rate and a relatively sharp drop in house prices.

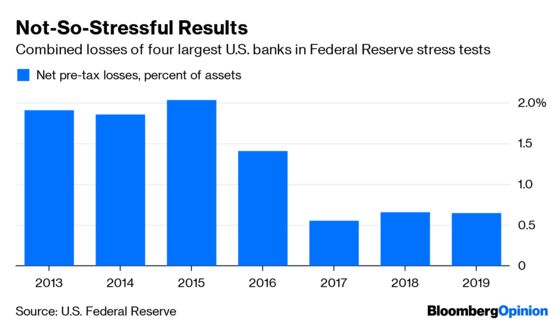

What really matters, though, is how the scenarios affect the banks. Even tough-looking economic scenarios don’t necessarily have much impact on balance sheets, partly because the Fed’s models involve judgement and can’t replicate the complex interactions of a real crisis. The latest exercise offers a case in point: Total hypothetical losses at the four largest U.S. banks didn’t exceed 3.5% of assets, compared with as much as 6% in the 2008 crisis. Net of income, the losses were just 0.7% of assets -- the same as in the 2018 tests and less than half what the 2013 tests generated.

In other words, the stress tests aren’t doing their job. They’re providing a justification for banks to pay out equity capital in the form of dividends and stock buybacks, instead of pushing for more loss-absorbing capacity. This is a problem, because banks don’t have enough. On average, the country’s six largest have less than $7 in equity for each $100 in assets. Research and experience suggest they need more than twice that amount to make the chances of a bailout adequately remote.

There’s a much simpler way to ensure that the banking system will be more resilient when the next big downturn hits: Set higher capital requirements in the first place. As it happens, the Dodd-Frank Act gave the Fed a helpful tool to do so: the countercyclical buffer, which empowers it to increase capital requirements “in times of economic expansion.” Officials have so far been hesitant to use it. They would do well to reconsider.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Whitehouse writes editorials on global economics and finance for Bloomberg Opinion. He covered economics for the Wall Street Journal and served as deputy bureau chief in London. He was founding managing editor of Vedomosti, a Russian-language business daily.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.