(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The bond market needs to take the Federal Reserve at its word this time. After pushing the central bank to accept that the current high rate of inflation was not transitory, bond traders have turned relatively sanguine on how much the Fed is likely to tighten monetary policy now that it has acknowledged it needs to act. So much so, that Fed Chair Jerome Powell had to twice make clear in less than a week that the central bank will do whatever it takes to bring down inflation rates that are hovering around 8% annually. And he managed to surprise the market both times!

There was no doubt after last Wednesday's policy decision, when the Fed raised its key interest rate for the first time since December 2018 --boosting it from near zero to a range of 0.25% to 0.5% — and signaled more were on the way, that Powell had given up his dovish leanings and become a true hawk. But it wasn’t until Powell doubled down on his message this week that the Treasury market finally started to take heed, even assigning a greater chance that the Fed will engineer one or more supersized rate increases of a half percentage point at policy meetings in coming months.

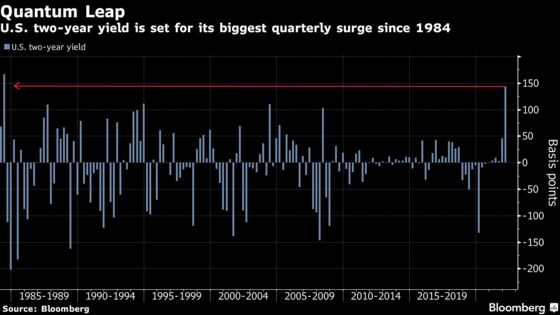

Yields on Treasuries securities of all maturities have jumped, with those on two-year notes poised for their biggest quarterly increase in almost four decades. The gap between the five- and 30-year yields shrank to the narrowest since 2007. Other parts of the yield curve have inverted, a signal to some that tighter monetary policy will cause a recession before long. The fallout reverberated across global bond markets, with the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index off to one its worst starts ever, tumbling 6.55% this year already.

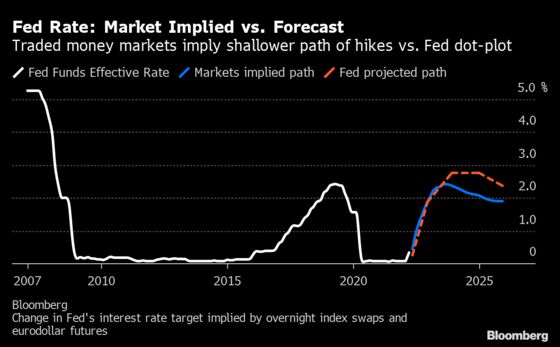

And yet, traders and investors still don’t seem convinced that the Fed will be as aggressive in tightening policy as the hawkish rhetoric suggests. The S&P 500 Index is up more than 5% from the day before the Fed raised rates, and the eurodollar futures market suggests traders are positioning for the Fed to start cutting rates by 2024, before it even reaches its target terminal rate of 2.8%.

The market's hesitation is somewhat puzzling considering that the consumer price index just rose 7.9% from a year earlier, the war in Ukraine is pressuring energy and commodity prices higher, and inflation expectations risk becoming unanchored. Of course, investors have their reasons. Having stuck with the transitory inflation assumption far too long, the risk now is that the Fed errs again by over-tightening and hurting the economic recovery. That's the narrative that emerges from the yield curve and the action in the rates futures market.

There’s another reason the bond market doubts that rates can rise too much: $30 trillion. That’s the total U.S. public debt outstanding, which has swelled from around $10 trillion at the time of the financial crisis back in 2008 amid historically low borrowing costs. A surge in rates would make that massive pile of borrowings much more costly for the government to service, potentially causing what is known as a debt spiral.

Even so, the market may need to acknowledge that the Fed may have no choice but to raise rates faster and higher than anticipated if it wants to get inflation under control. An informal survey by Bloomberg News found that a vast majority of market professionals believe major central banks are behind the curve when it comes to controlling inflation. Powell’s recent comments suggest an urgency and the realization that the Fed has some catching up to do. What’s telling is that he said the Fed is prepared to raise rates beyond what is believed to be a neutral level, adopting “a more restrictive stance” if needed.

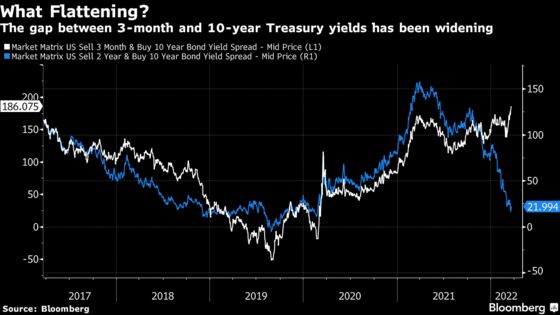

In other words, the Fed will keep raising rates as long as inflation remains elevated even if the economy stalls. And what about that yield curve and inversions? Powell dismissed the significance of readings for anything beyond two-year maturities. The Fed itself is looking at a part of the curve that is almost as steep as it gets, which is the difference between rates on securities due in 18 months or less, and the difference between three-month bill rates and 10-year yields, which is about the widest since March 2017.

There is plenty of debate about which measure of the yield curve is more indicative about the health of the economy, especially given evidence that the Fed’s quantitative easing measures have distorted the yield curve. Regardless, Powell drawing attention to the part of the curve that’s not flattening means the Fed thinks it can aggressively raise rates to get control of inflation after waiting too long to take action. The Fed now knows it’s behind the curve, and the market needs fully accept the central bank’s new position.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jenny Paris is executive editor at Bloomberg News for global bond, currency and emerging markets. She has previously worked at the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones Newswires covering the euro zone crisis and as a managing editor for Asia equity markets.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.