Here’s What Could Go Wrong With Yield-Curve Control

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- To fight the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic, some have suggested the Federal Reserve turn to a tool it hasn’t used since World War II: yield curve control.

The Fed — which holds its annual monetary policy symposium from a virtual Jackson Hole this week — has resisted the idea so far. But financial markets seem to expect it to relent at some point. It’s worth thinking of the long-term economic risks.

Normally, government bonds with longer maturities have higher interest rates. The longer the time horizon, the greater the risk of inflation (or sovereign default) along the way, requiring a higher return as compensation. Normally, the Fed only controls short-term interest rates; cutting them makes long-term rates fall too, but the premium on longer-term bonds stays roughly the same.

Under yield curve control, the Fed also lowers the premium on longer-term bonds. It did this during the Great Recession when it engaged in quantitative easing; but under yield curve control, the Fed explicitly declares its target for long-term rates. This has the advantage of potentially avoiding another large balance sheet expansion, as presumably private market participants will simply trade Treasuries at the target rate, instead of forcing the Fed to actually buy the bonds to push rates down.

The question, however, is why the Fed would do this. In the Great Recession, the purpose of pushing down long-term rates with QE was to spur the private sector to borrow more money to get the economy going. This time, however, the Fed is already lending money directly to borrowers. Low long-term rates might provide some additional stimulus, but the main effect would be to make the federal deficit more sustainable. By keeping long-term rates low, the Fed will ensure the Treasury can borrow whatever it needs to sustain households and businesses through the pandemic, without worrying about rolling over short-term debt. The Fed controlled the yield curve during World War 2 to help finance the war effort. A pandemic is somewhat like a war, so the rationale is similar.

In a once-in-a-century pandemic, it’s good for the government to be able to borrow cheaply. Special unemployment benefits, support for struggling businesses, and programs to quell the virus itself are all worthy spending items, and all are short-term programs that won’t persist once coronavirus is gone. Thus, yield curve control can act as a sort of insurance policy, making sure the government is free from macroeconomic headaches while it does what it needs to do.

But if the policy persists after the pandemic is over, there could be problems. The first is that nobody really knows the effect of Fed interest rate caps on the economy during normal times. A few economists worry persistently low rates give rise to unproductive zombie companies that survive only by rolling over cheap debt and compete healthier companies out of the market. It’s also possible low rates could benefit big companies more than small ones, exacerbating the problem of monopoly power.

The second danger is inflation. Right now, with demand crushed by the pandemic, inflation seems unlikely, but when normal times return, yield curve control could cause prices to rise. If investors are unable to get a premium for buying longer-term Treasuries, they may abandon that market, forcing the Fed to step in and actually buy the long-term bonds to maintain its rate targets and keep government borrowing costs low.

And yield curve control could lead to a situation known as fiscal dominance, in which monetary policy becomes subordinate to the needs of Congress. If businesses think the Fed will simply create as much money as it needs to finance government deficits, then they may expect a spike in inflation. This would cause them to raise prices, making inflation a self-fulfilling prophecy. That might be what happened in the late 1940s; the Fed kept controlling the yield curve after the war, but stopped doing so after inflation rose to 17%.

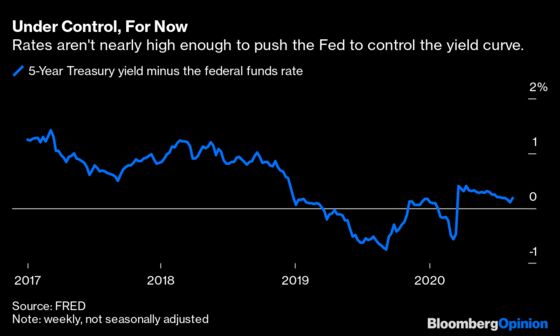

Given these long-term dangers, the Fed is understandably reluctant to commit itself to a policy that might be politically difficult to end. Besides, while term premia are a little higher than before coronavirus struck, they’re still pretty low:

So the Fed is holding off on yield curve control for now. But if investors get jittery and start demanding higher yields on longer-term government debt, the Fed may end up having to take over. For better or worse.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.