(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.S. labor market poses a conundrum: The unemployment rate is at lows last seen 50 years ago, yet runaway wage growth or inflation is absent. This has left analysts and economists with a persistent and nagging question: When will the economy hit full employment (which generally means that all available labor is employed in the most efficient way possible)?

Although the answer isn't at hand at the moment — Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, doubts we're there yet — it's clear that the country didn't hit full employment in the last economic cycle. In retrospect, this also suggests the Federal Reserve kept monetary policy too tight then, and that policy makers should be more thoughtful about how to head off the risks that accumulate during economic expansions like the one we're in now.

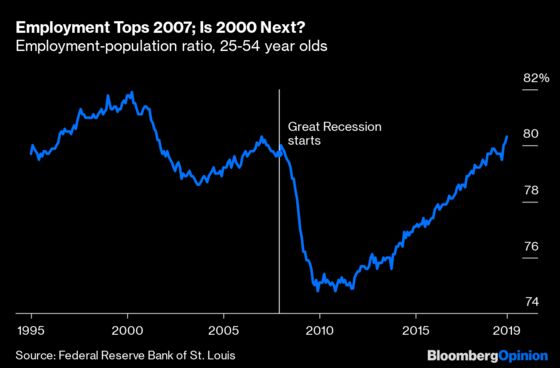

Just by way of comparison, today's unemployment rate of 3.6% is well below the 4.4% low reached in 2007. Inflation, meanwhile, remains a bit below the Fed's 2% target. At the same time, the percentage of prime-aged workers gainfully employed finally matched its 2007 peak, but still is short of its 2000 high.

It's instructive to look at how the Fed responded to declining unemployment in the '00s. Between June 2004 and June 2006 the Fed raised its overnight target interest rate from 1% to 5.25%. It did this even in the clear absence of full employment and inflation that never reached a level that was cause for concern. In short, monetary policy became too tight. At the same time, there were huge excesses building up in the financial system, credit markets and the housing market that needed addressing. It's important for the Fed to recognize this if we're going to have more effective monetary policy in the future.

Relying solely on rate hikes was the wrong way to address the mounting risks between 2004 and 2007. With the benefit of hindsight, a better policy mix would have kept interest rates lower for longer while doing things like increasing collateral and capital requirements for banks engaged in risky activities and imposing stricter underwriting regulations for mortgages.

More intensive supervision and regulation, like the Fed's annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review — which includes stress tests for the biggest banks — are complementary to monetary policy. When inflation is low, reining in financial excesses brought on by low interest rates are best handled this way. The unwelcome alternative is to increase interest rates to levels that hurt economic growth and the labor market.

Thinking about financial system risks apart from the labor market and inflation now should be standard for policy makers. For instance, although inflation is low today, the growth of corporate debt and leverage is becoming a concern; debt has boomed as investors in search of yield are happy to lend money at low interest rates, and giving companies the wherewithal to do little more than fund stock buybacks. To rein in this corporate borrowing binge, the Fed could raise interest rates multiple times, making it more expensive for corporations to borrow. But in doing so, the central bank would hurt the housing market, strengthen the dollar and make exports less competitive, harm manufacturers, and create deflationary pressures.

Alternatively, regulators could make it more expensive for banks to hold corporate debt. In the event of an economic downturn that leads to outsize losses on corporate debt, the banking system would be less likely to be damaged in the process.

The Fed clearly was in error in the last cycle when it used rate hikes when the problem was the buildup of risks in the financial system rather than inflation. Maybe policy makers can do better in the future. It seems clear that the central banks should reserve rate hikes for inflation and inflation alone. For risks in the financial system, supervision, regulation and capital adequacy must be the tools of choice. If the Fed curtails the excesses that accompany economic expansions, we have the opportunity to sustain very low or even full employment for longer than at any time in the past 20 years.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a portfolio manager for New River Investments in Atlanta and has been a contributor to the Atlantic and Business Insider.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.