(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Federal Reserve officials have made clear that if all goes according to plan in 2020, it’ll be a rather quiet year. They expect to hold the fed funds rate, the central bank’s key lending benchmark, steady throughout the next 12 months.

It’s true that on that front, they won’t have much to discuss when they gather this week for the two-day Federal Open Market Committee in Washington. The Fed will stick to its current range of 1.5% to 1.75%. Chair Jerome Powell will reiterate that the economy is in a “good place” and that it would take a material change to the outlook to even consider moving in either direction anytime soon.

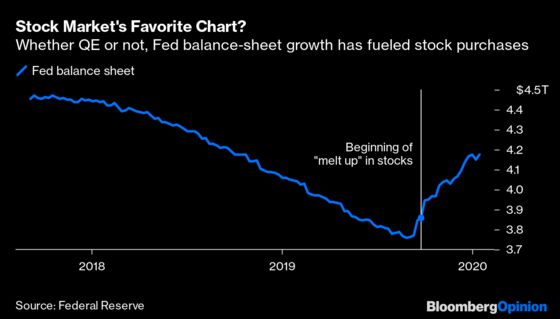

There’s still a chance for some fireworks, however, especially after Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari caused a stir this month by publicly calling out “QE conspiracists,” or those who argue that the central bank’s purchase of Treasury bills is no different from typical quantitative easing and responsible for the rally in U.S. stocks.

The problem with that framing, of course, is Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan said just two days earlier that balance-sheet expansion was partly why asset prices are higher, calling the current program “a derivative of QE.” He added: “Growth in the balance sheet is not free. There is a cost to it.” Bloomberg TV’s Jonathan Ferro asked the “QE-or-not-QE” question to a range of high-profile executives in Davos, Switzerland, last week. Many, including Morgan Stanley Chief Executive Officer James Gorman, sided with Kaplan.

Powell won’t be able to dodge this question. In December, there was still no clarity about the outcome of the U.S.-China trade war, while at the same time a potential year-end crunch in the repo market was top of mind for bond traders. Both of those risks are now gone. Instead, the most-pressing question for investors is whether a 15% surge in the S&P 500 Index and massive tightening of high-yield spreads since early October are sustainable or just a setup for a reversal once the Fed winds down its balance-sheet expansion.

The Fed’s predicament is that its current bill-buying program truly isn’t QE, at least not in a traditional sense. But as Bloomberg News’s Elena Popina succinctly put it, which was the trigger for Kashkari’s tweet: “The Debate Over Whether to Call It QE Is Over, and the Fed Lost.”

NatWest Markets strategist Blake Gwinn summed it up like this in a Jan. 24 report:

We generally find the bill purchases to be lacking in most of the typical ways we think about balance sheet expansion providing “easing.” That being said, this could be one of those scenarios where if enough people believe a relationship exists (or at least avoid positioning against it) that relationship becomes real. This is why we think a slowing of the Fed’s bill purchases could eventually still lead to a modest equity selloff – not because there is any direct link between those purchases and equity valuations or flows, but simply because enough investors believe it should be bad for stocks.

It’s hard to overstate what a tricky position this is for the Fed. It’s not that officials are necessarily opposed to higher risk-asset prices, but they don’t want markets to be entirely dependent on whether or not they’re increasing the level of bank reserves. Kaplan said he hopes they can find a way to temper balance-sheet growth. History has shown that it could go rather smoothly, as when former Fed Chair Janet Yellen equated a runoff of maturing debt to “watching paint dry,” or it can cause an uproar, like the 2013 “taper tantrum.”

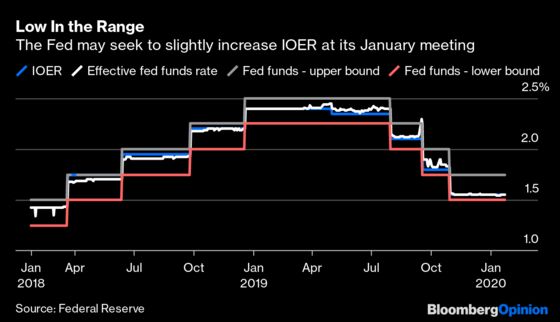

As if there weren’t already enough scrutiny over the Fed’s balance sheet, the central bank also has a decision to make on the other rate it controls — the interest on excess reserves, or IOER. Strategists at Barclays Plc, BMO Capital Markets, Citigroup Inc. and TD Securities all expect policy makers to raise it by 5 basis points this week, while Morgan Stanley thinks it’s too soon. Overall, about a third of economists surveyed by Bloomberg predict a boost.

To many casual observers, this question might seem like inside baseball. Indeed, until 2008, IOER wasn’t a part of the Fed’s monetary policy toolkit. And even in the years after the financial crisis, no one seemed to pay it much mind anyway, given that short-term rates were pinned near zero. It has only been in the past few years, when the Fed gradually raised interest rates and then swiftly dropped them, that it has drawn more attention.

However, the main function of IOER is to keep the fed funds rate within the set target range. It failed to do that during the repo market meltdown in mid-September, raising uncomfortable questions for the Fed about losing control of monetary policy. Since then, the rate has been stable, though close to the bottom of the range. Thus, the potential need for a 5-basis-point increase.

Again, this is mostly technical. As RBC Capital Markets strategists put it in a Jan. 23 note:

It is certainly possible they adjust [IOER] at the coming meeting, though the timing and adjustment itself is largely irrelevant insofar as economic implication are concerned. More logically, the Fed could make this technical adjustment once the bulk of the current asset purchase program ($60b/month in T-bills) ends and reserves are deemed to be “very ample” again. The market could view this as some modest de-facto tightening after the Fed added significant liquidity to the system.

I’d argue that Fed officials are desperate for bond traders to not overthink any tweak to IOER, which is why they might opt to get it out of the way now. It already feels daunting enough for the central bank to end its bill-buying effort. Adding any sort of rate increase after that would make it that much harder. As it stands, most economists surveyed by Bloomberg see the Fed halting its bill purchases by June after first tapering them.

All of these decisions will matter, even if the headline fed funds rate doesn’t change. This quiet year could very well start off with a bang.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.