(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Despite President Donald Trump’s repeated efforts to get the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates, Chairman Jerome Powell has wisely refused to address the president directly. Doing so would risk the Fed’s independence.

Powell does, however, have to answer the general charge. Inflation is lower than the Fed’s 2% target, so why not lower interest rates as a precautionary measure in these uncertain times? Powell’s response has been twofold. First, he says, the low inflation is the result of “transitory factors” that will soon dissipate. Second, he notes that the Fed has scheduled a conference in early June to discuss whether any changes are needed to its long-term framework.

The Fed’s own economists are now challenging the first point. And outside researchers — from both ends of the political spectrum — are questioning the second.

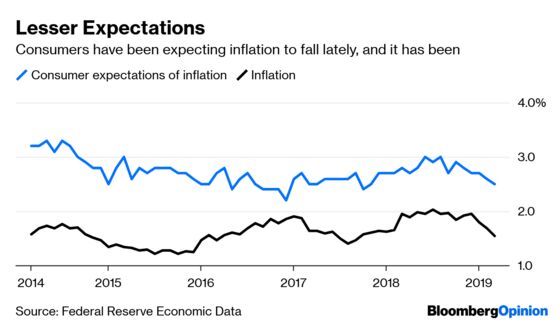

Newly released meeting minutes show that the Fed’s own staff no longer believes that the current low inflation is temporary. Consumer expectations of inflation, a crucial component in determining how much room businesses have to raise prices, are now falling.

As for the long term: Skanda Amarnath, director of research at the new left-of-center think tank Employ America, argues that the Fed needs to recalibrate its entire approach. Inflation is a lagging indicator, he says. A much better gauge of the economic conditions facing businesses is something Amarnath calls gross labor income: the cumulative sum of each worker’s paycheck. If gross labor income is falling, then consumers will have to cut back on spending, and that means businesses will have less pricing power.

Amarnath suggests that the Fed worry less about inflation and more gross labor income. Doing so would prevent the economy from slipping into a recession and would provide businesses with steady expectations about future demand.

Amarnath recommends that the Fed raise rates only when two conditions hold: total wages are growing steadily, and inflation is projected to rise above 2%. This so-called “asymmetric” approach would keep the Fed from raising interest rates during a productivity boom. Such a boom could provide businesses with the room to raise wages, without leading to inflation.

Amarnath’s proposal shares a lot in common with a popular approach on the right called nominal GDP targeting. Unlike gross labor income, nominal GDP also takes into account interest, rents and profits earned by businesses. Amarnath argues that gross labor income is the more responsive indicator. Rents are slow to change and profits are hard to estimate in real time.

Scott Sumner, an economist who is a strong supporter and promoter of using nominal GDP, has himself said that a measure that accounts only for wages might be economically more efficient. But he views it as a political non-starter; the Fed can’t be seen to be favoring workers over business owners.

Critics on the left point out that the Fed has been implicitly doing just the opposite for years — that’s why labor has seen its share of income fall steadily for nearly two decades. I think that critique is largely accurate. The solution is for the Fed to stop favoring either side and weigh the interests of both owners and workers in its framework.

At any rate, economists on both the left and the right are converging on an approach that is broadly similar and far more radical than anything the Fed seems to be considering. When monetary officials meet in June, they need to take these critiques to heart.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Michael Newman at mnewman43@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith is a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina's school of government and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.