Fears of a Too Hot Economy Ignore Racial Inequality

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Joe Biden recently unveiled his $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan that proposes investments in transportation, manufacturing, caregiving, and research and development, as well as universal access to safe drinking water and high-speed Internet. The policy wonks are scrambling to evaluate its economic effects, as well as the proposed increases in corporate tax rates to pay for it. Many are sounding the alarm about pushing gross domestic product past “potential output,” and that’s before Biden’s American Family Plan, the details of which are expected later this month.

After spending almost $6 trillion to fight the pandemic and bolster the economy, inflation hawks see anything that spurs a spike in demand as an existential risk. But be wary of arguments that wield “potential output” as a club. Its framework is discredited, and it is time for new tools and new thinking.

What is “potential output,” and why is it central to the debate over fiscal policy? Simply put, it is an estimate of how much gross domestic product the U.S. can produce given how much people are want to work, the capital that businesses have and how effective these inputs are at making stuff, namely, productivity. The conventional thinking is that producing more than potential will “overheat” the economy, leading to much higher inflation.

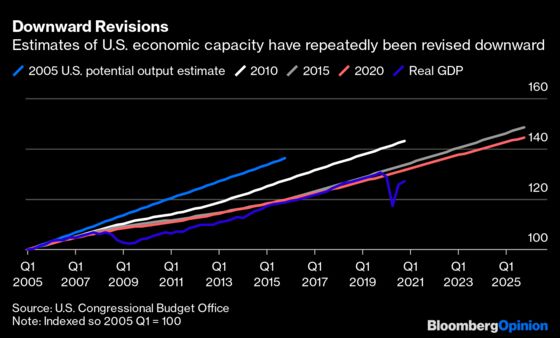

The bottom-up approach for estimating potential output dates to the 1960s and, despite methodological refinements over time, has serious flaws. In times of great economic change, official estimates from the Congressional Budget Office can be subject to massive revisions. As I wrote in a policy brief recently, if the economy’s potential had grown as CBO expected in 2005, it would be higher by $4 trillion now, or about 20% of GDP.

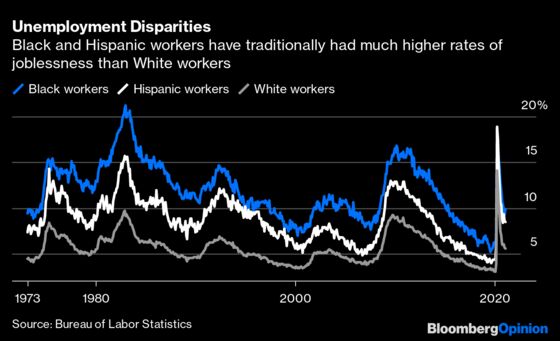

An even more troubling flaw is that estimates of potential output basically assume that our past must be our future. As one example, it takes systemic racism that has kept many people of color on the sidelines of the labor market as a permanent feature of the economy. Alex Williams at Employ America, a progressive think tank, points out that the CBO assumes unemployment rates by age and race seen in 2005 are the lowest we can attain without sparking inflation. In other words, our potential is stuck in the past.

And it’s a dismal past. In 2005, the Black unemployment rate was 10%, or 4 percentage points above its half-century low in 2019 , at a time with only moderate inflation. Since the 1970s, Black workers are twice as likely as White workers to be unemployed and Hispanic workers are 1.5 times more likely. On many dimensions, racial and ethnic groups have been hardest hit in the pandemic.

The first change to our thinking should be defining the potential of the economy in terms of future opportunities for all workers, not the historical barriers that some have faced. Using the current approach to potential output to evaluate government programs implicitly accepts that discrimination is embedded in the economy. An unobservable, educated guess based on embedded racism should not be used to judge programs designed to push the economy to full employment and reduce inequality.

As a first step, during this crisis, the Federal Reserve has moved its focus more toward employment rather than inflation. Throughout the past year, Chair Jerome Powell and a chorus of policy makers have drawn attention to the million jobs lost and the crushingly high unemployment rates, especially among Black and Brown workers.

Second, we need more timely and more detailed economic data by race, gender, and their intersection that can inform policy. Rhonda Vonshay Sharpe, founder and president of the Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race and Bloomberg Opinion contributor, explain that with existing data and standard analysis, we cannot fully grasp the suffering among minorities in this crisis and the challenges they face. Money allocated to statistical agencies to enrich their data would pay off in terms of better policies.

Finally, we must understand that discrimination is holding back economic potential. The $180 billion for research and development in the American Jobs Plan won’t attain its maximum impact if we don’t include researchers, such as in sciences, engineering, and medicine, who are also minorities. Lisa Cook, a professor at Michigan State University, found that discrimination and racial violence in the 19th and early 20th centuries led to 60% fewer patents by Black inventors during the period. A recent survey by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation found that Black people make up 0.3% of innovators, far below their 11.3% share of the population. That lack of diversity reduces GDP and our true potential.

It’s time for economists to update their tools and open their minds to what’s possible, and it’s time for policy makers to engage with the economic realities of systemic racism and fight to end it. Good intentions are not enough, words are not enough. Economists will need to critically evaluate legislative proposals to reduce racial disparities and expand economic potential. And they need better tools to do it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Claudia Sahm is a Senior Fellow at the Jain Family Institute and a former Federal Reserve economist. She is the creator of the Sahm rule, a recession indicator.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.