Falling Mortgage Rates Aren't What They Used to Be

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The 30-year Treasury yield has been spending some time below 2% this week, territory it has never before explored. That says scary things about expectations for future inflation and economic growth. But it also means lower mortgage rates, which in turn means refinancings and house purchases and other economically stimulative things.

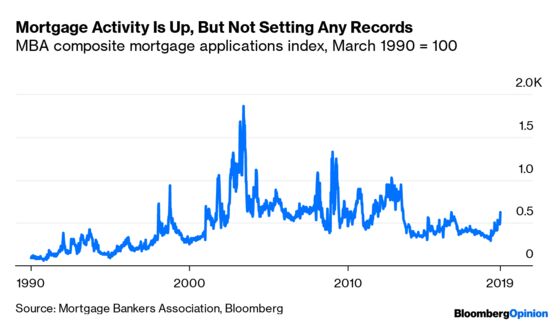

And yes, a lot of people are refinancing, with the latest edition of the Mortgage Bankers Association Refinance Index, released Wednesday, up 196% over a year before. Some are buying, too, with MBA’s Purchase Index up 12%. Those numbers represent conditions as of August 9, and things may have continued to heat up since then. But overall mortgage activity has a long way to go before it approaches the heights it has reached multiple times over the past two-and-a-half decades.

The explanation for the relatively modest mortgage rebound so far is simple. As economists David Berger, Konstantin Milbradt, Fabrice Tourre and Joseph Vavra put it in a December 2018 paper:

Suppose that the current interest rate is cut from 3% to 2%. If rates were previously 3% for a long period of time, then many households will have an incentive to refinance their mortgage debt, which can then lead to increases in spending. In contrast, if rates were previously below 2% for a long period of time, then many households would have already locked in a low rate and will have no incentive to refinance in response to today’s rate cut.

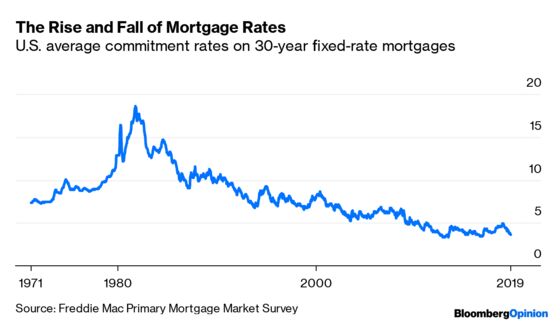

Mortgage rates are very low now in the U.S., but they were similarly low in 2012, 2013, 2015 and 2016. Since about 2011, the long downtrend in rates that began in the early 1980s seems to have been replaced with a rough approximation of a flat line.

As the 30-year Treasury toys with 2%, mortgage rates could follow it lower, of course. But it will take quite the drop to replicate the kind of stimulus that falling rates brought in the early 2000s and early 2010s. From 2000 to 2003, the 30-year mortgage rate fell by 3.1 percentage points. From 2008 to 2013 it fell by 3.2. That big a drop from the peak of December 2018 would entail a 30-year mortgage rate of 1.6%. These days I wouldn’t say anything having to do with falling interest rates is unimaginable, but it does seem quite unlikely.

As University of Chicago economist Austan Goolsbee outlined in a New York Times column earlier this month, similar scenes are playing out in other debt markets, severely limiting the Federal Reserve’s ability to stimulate the economy by cutting interest rates. And hey, maybe it doesn’t need to: Unemployment is low, consumers are buying, the economy is still growing. But those record-low 30-year Treasury yields do seem to imply worry that this growth won’t continue.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sarah Green Carmichael at sgreencarmic@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.