(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A major restructuring is looming at China Evergrande Group. The nation’s second-largest real estate developer has been in talks to sell equity stakes to third-parties; and its billionaire founder Hui Ka Yan has stepped down as chairman of Hengda Real Estate, its main asset in the mainland, according to National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System, a website that maintains the public records of local companies.

Is this good or bad news? Hengda and Evergrande mean the same thing in different languages. The first is the Chinese pinyin translation of the second. But they are now essentially two different corporate entities, and it’s likely foreign investors will be lost in the translation.

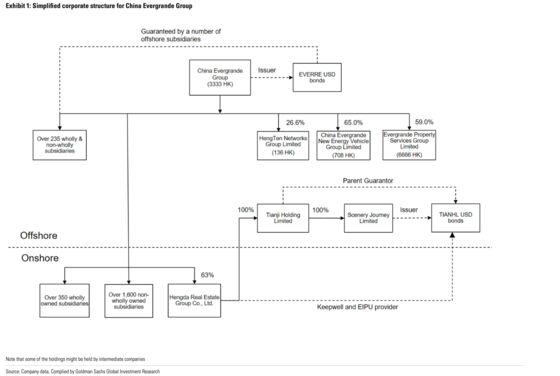

Evergrande is Asia’s largest high-yield dollar bond issuer, with about $19 billion outstanding. By stepping down as Hengda’s chairman, Hui is distancing the Hong Kong-listed parent, which is incorporated in the Cayman Islands, from its main onshore asset, at least in the eyes of China’s legal system. If foreigners were hoping to recoup some of their investment from the more solid mainland assets, good luck: Hengda is the very pretty kite that’s floating farther and farther from reach.

Even though Evergrande owns most of Hengda, the real estate unit may no longer be responsible for the parent’s troubled finances.

In the West, a person or entity with the most shares is in control of a company. In the mainland, however, a person who is the company’s legal representative and is in possession of the company seal has control, even if he does not own a stake. We’ve seen some high-profile examples recently, including SoftBank Group Corp.’s battle to oust ARM China’s boss Allen Wu, who has the company seal (which is used to stamp all legal documents). The party that controls the seal is king (a rule established centuries, even millennia ago.)

Chinese courts have continued to recognize the archaic practice in recent restructuring cases. It’s particularly helpful when cutting through the spider-weblike ownership charts of conglomerates. Earlier this year, when the High People’s Court of Hainan Province ruled on the restructuring of HNA Group, it used the legal representative framework to decide which affiliates should be considered part of the conglomerate — and benefit from the financial relief that comes with it.

Similarly, in the case of the restructuring of Tsinghua Unigroup Co., some of its indirect subsidiaries that are asking to be part of that process base their arguments not on share ownership but because their legal representatives “acted together” with Unigroup’s. The conglomerate at one point had the grand ambition of becoming China’s Samsung Electronics Co.

Hypothetically, Hengda’s assets may not even be available for Evergrande’s foreign investors to claw back some of their losses. It’s a far worse scenario than that faced by investors in HNA, where the restructuring included operating assets such as Grand China Air. According to a Goldman Sachs Group estimate, Hengda as of 2020 accounted for about 80.6% of Evergrande’s total assets — now under separate management. Hengda also holds 73.7% of Evergrande’s debt. In this scenario, Hengda would just take care of its own creditors and survive on its own, leaving the parent to fend for itself.

This goes back to the point I made last week. Over the years, companies adept at raising billions of dollars offshore also tend to be financial houses of cards, with complex offshore and onshore corporate structures. The offshore parents’ ties to onshore operating assets can be severed. Evergrande, for instance, should just be seen as an investment company that owns some stocks and a few residential buildings dotted across Hong Kong. It’s not really China’s second-largest real estate developer. That would be Hengda, which is now out of reach behind the mainland’s financial walls.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.