(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s not quite Wall Street’s version of the “Great Resignation” — but it’s not too far off, either.

JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s equity derivatives desk has faced a wave of defections this year, part of a growing trend across the financial industry, Bloomberg News’s Hannah Levitt reports. Unlike many Americans leaving their jobs, JPMorgan’s senior executives had positions lined up at rival powerhouses like Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc. and Millennium Management. But, like workers in other industries, bankers are increasingly basing their career decisions on more than just money. After more than a year of the Covid-19 pandemic, flexible lifestyles are in demand.

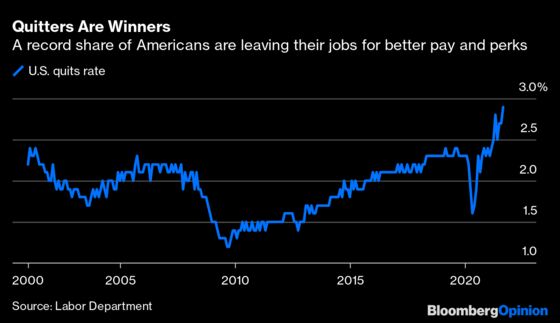

This nationwide trend is reflected most prominently in the “quits rate,” a measure of employee-initiated job separations that’s part of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey. It reached a record high 2.9% in August, compared with 2.3% at the start of 2020, when many economists considered the U.S. at a level consistent with maximum employment. The jump reflects ample confidence among job-seekers that they can find appealing positions elsewhere. The latest Jolts data will be released on Friday.

Crucially, the quits rate is also a key indicator of U.S. labor market strength. “Wages is a key measure of how tight the labor market is. The level of quits. The amount of job openings,” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said at a press conference last week. “Quits and job openings and wages and things, many of them are signaling a tight labor market, but the issue is, how persistent is that?”

The fact that JPMorgan and other Wall Street institutions aren’t immune to greater turnover at their highest ranks is good reason to think the tightness is quite persistent. It’s been clear for a while that with job openings at near-record highs, including among restaurants and other front-line industries, employers have had to offer higher wages and bonuses to attract candidates who might otherwise rather wait out the pandemic. Hourly workers in the leisure and hospitality industry saw earnings jump by 12.4% in October relative to a year earlier, for instance, according to Labor Department data.

The top ranks of the financial industry are outpacing even that robust wage growth:

For now, industry veterans examining their options have found they have more alternatives than before. A growing number of financial-technology companies, crypto-currency ventures and so-called blank-check companies are interested in enlisting their experience.

So how much can a banker get by jumping ship? It depends.

The standard bump of at least 10% that executives could expect by defecting to a competitor has probably doubled, said Robert Voth, managing director at executive search firm Russell Reynolds Associates.

At least in the context of the broader labor market, this is perhaps the most critical line from Levitt’s reporting:

An industry veteran said moves are becoming so common that some people left behind are anxious: Are they making a mistake by staying?

At a time when special-purpose acquisition companies and cryptocurrencies have minted fortunes, it’s hard not to imagine that this doubt has creeped into into the psyches of U.S. workers across industries. What is company loyalty worth if the new hire at your level is making significantly more money? Will firms raise their pay scales internally to retain employees with institutional knowledge, or will they just accept whatever turnover happens? As the end of the calendar year draws near, these will be crucial decisions for executives who are balancing wage pressures and rising prices, all while attempting to maintain current profit margins.

Either way, employees’ unusual propensity to quit raises the risk of a wage-price inflation spiral — not something the Fed or the Biden administration wants to contemplate with the U.S. consumer price index rising at its fastest pace in three decades. Powell, for his part, sees it as a mismatch between worker supply and demand. “You have people who are held out of the labor market, you know, of their own, they're holding themselves out of the labor market because of caretaking needs or because of fear of Covid or for whatever reason,” he said. To be sure, a return to a normal participation rate is possible.

But it could also be the case that some Americans 55 and older, who are more likely to have sizeable financial assets that have lately soared in value, aren’t particularly interested in returning to work, regardless of any salary boost. As my Bloomberg News colleague Cameron Crise noted, “there has never been a postwar recession where either the employment or participation of older workers has lagged this badly. That’s flashing an amber warning signal that something is different this time around.” On the opposite side of the spectrum, if you believe survey data posted on Twitter last week by Mark Cuban, a portion of the labor force (presumably on the younger side) has quit because of gains from trading crypto.

For policy makers, none of this means it’s time to slam the panic button yet. But, to use Powell’s term, it might be wise to contemplate “risk management.” The central bank is leaning on its vague maximum employment mandate to justify keeping interest rates near zero at least through mid-2022. If something about this labor market is truly different — say, if ultra-accommodative policy is fueling speculative bubbles and discouraging labor-force participation — that could be a mistake. Of course, that kind of knowledge unhelpfully comes only in hindsight.

JPMorgan, with its 265,800-person workforce — the largest in U.S. banking — offers at least a bit of forward guidance. Even with competitive pay and the bank’s prestige, departure rates in many of its businesses are reportedly up at least a few percentage points from pre-pandemic levels. It stands to reason that much of corporate America is dealing with similar issues. After all, if CEO Jamie Dimon isn’t impervious to labor market forces, no one is.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.