Leverage on Leverage Is Big Danger for Investors and Their Lenders

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s already too much money chasing too few assets and yet even the most sober investors seem ready to add to the problem.

Calpers, the $495 billion California public-employee pension fund, is planning to put more money into chasing returns by taking on debt worth up to 5% of its fund value — or roughly $25 billion — to plow into financial assets. It is doing this because it can’t see another way of hitting its long-term return target of 6.8% to meet its promised payouts.

This seems remarkable to me: A very big pension plan, which invests in lots of different funds, including many that use leverage to boost returns, is now going to start using its own leverage on top to try to boost its returns. It highlights how investors of all kinds are having to take more risk to make any money.

Calpers’s strategy may ultimately be self-defeating: The more money you throw at any asset class, the lower its yield goes and the harder it becomes for anyone to earn a good return. Yes, I know fresh assets get created — new companies, new bonds and new joke Shiba-Inu Coins, or whatever. But markets have been flooded with money to battle the fallout of the Covid pandemic, boosting prices and depressing future returns everywhere.

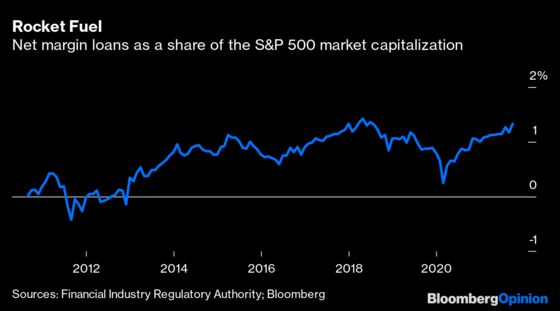

The other issue is that leverage in financial markets is high – and rising – and that makes things riskier and potentially unstable. Let’s just look at companies. In U.S. stock markets, the amount of borrowed money behind share prices has hit a record high. Net borrowing on margin in brokerage accounts hit $509 billion in October, according to the latest data from the U.S. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or Finra.

Margin lending has grown rapidly this year, breaking new records almost every month. But stock values have risen rapidly, too, so the way to judge the importance of this borrowing is to compare it with market capitalization. Against the S&P 500, the amount of margin dollars per dollar of market capitalization is also close to record levels. It was slightly higher only during three months in the summer of 2018, and it could surpass those levels in November.

Another way to invest in companies is through private equity. Guess what: Buyout deal valuation and leverage multiples have also jumped. The price tag on more than two-thirds of U.S. buyouts last year was more than 11 times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (Ebitda), according to consultants at Bain & Co. At the peak of the last buyout boom in 2007, only about one-quarter of U.S. buyouts were at such high multiples.

Meanwhile, total debt is more than seven times Ebitda on nearly 60% of deals, according to Bain & Co.; in 2015, it was less than 20% of deals.

And yet private-equity firms are adding more debt to these businesses in order to take out dividends at a record rate this year — even as the buyout frenzy continues. U.S.-based private-equity owned companies are on course to borrow nearly $90 billion to fund dividend payouts this year, the most since Bloomberg started collecting this data in 2013.

All of this is a danger for stock markets and investors, but also for banks, which provide the leverage in the first place. Some debt, such as margin loans, banks and brokers will keep on their own books. As for loans to big institutions, like Calpers, banks will sell some to other banks.

Meanwhile, the big loans that back private-equity buyouts are mostly all sold to other banks, mutual funds and structured vehicles called Collateralized Loan Obligations, or CLOs. But banks will hold lots of leveraged loans for a time while waiting for a buyout deal to close, or when acting as a warehouse for a new CLO while its managers are gathering enough loans to launch a the vehicle.

All these types of debt are secured against stocks or loans to protect the bank: If the borrower gets into trouble, then the bank gets to keep the assets. But here’s the rub, usually the borrowers get into trouble and banks get stuck with their assets when markets stumble, the assets drop sharply in value and selling them for cash isn’t easy. When this happens, everyone loses — including the banks.

A favorite worry of investors right now is an interest-rate shock next year to follow the inflation shock of this year, according to Michael Hartnett, chief investment strategist at Bank of America. The shock would be a quick and steep rise in interest rates, which is exactly the kind of thing that would pull the rug out from under all this leverage.

You’d never guess that investors — or their bankers — were remotely worried about this from how they appear to be behaving.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.