Europe’s Social Democrats Could Suffer Mass Extinction

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Here’s the state of Social Democrats across continental Europe: In two corners, Scandinavia and Iberia, they’re alive and well, having become pragmatic centrists or, as in Denmark, having turned hard right on issues such as migration. Almost everywhere in between — from France to the Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Italy — they’re in various states of disarray or dissolution. What happened? And is their decline terminal?

That’s what Germany’s SPD, founded 156 years ago as the ancestor of the movement, should be asking itself, as it convenes next week to anoint new leaders and decide whether to quit its coalition with the conservative bloc of Chancellor Angela Merkel. But this more existential question won’t be debated, at least not honestly.

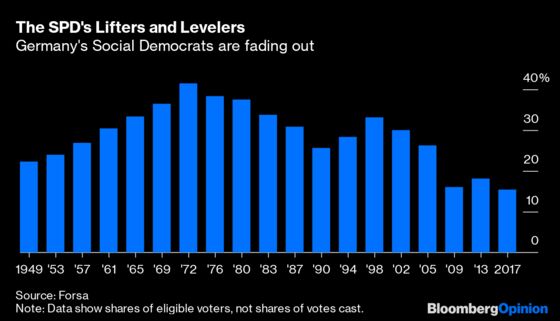

To get the big picture, look at the chart below. It shows the percentage of eligible voters in the Federal Republic of Germany who plumped for the SPD in national elections. What you see is a rise in the postwar years, when the SPD formally dropped its Marxist doctrines to appeal to potentially all Germans, not just the blue-collar types. The SPD then peaked in the 1970s under two Social Democratic chancellors, Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, who promised to lift more people into prosperity.

But in the 1980s and 90s, the ideological left wing of the party fought back. Lifting up was de-emphasized. Leveling down was the new message, as the SPD cast aspersions on “the rich.” Its support dwindled. The lifters briefly prevailed again over the levelers in 1998, putting the third Social Democrat in the chancellery, Gerhard Schroeder. But since then the levelers have dominated rhetorically. According to polls, the next bar in this chart will be the smallest yet.

Something similar has taken place around the neighborhood. The equivalent party in France, called PS, had an absolute majority of the National Assembly in 2012, then got overrun by the brand-new centrist movement of President Emmanuel Macron; it’s now irrelevant. Its Italian sister, called PD, is in government again, but as a much diminished junior partner to populists. Emulating Macron, Matteo Renzi, the PD’s former star, will quit and form his own party.

One lesson is that Social Democrats, not unlike the Democrats in the U.S., do well whenever they promise opportunity and badly whenever they preach, as Winston Churchill put it, “the gospel of envy.” But envy is all they’ve got these days. Hence calls by Germany’s SPD (and others) to bring back a wealth tax, even though it was suspended in the 1990s because it was a nightmare to assess and brought in little revenue.

Another lesson: You can’t just keep looking for new demographic groups that allegedly suffer some urgent “injustice” that must be fixed (by Social Democrats, of course). But that’s what the SPD keeps trying. It has just spent months haggling with its coalition partners to top up the state pensions of low-income retirees who’ve paid into the system for 35 years or more. Why not 34 years? Nobody knows. Not discussed was the unsustainability of the whole pension system, in which ever fewer young people will pay ever more of their income to ever more old people. As usual, the SPD is baffled that it hasn’t risen in the polls.

The bigger insight is that the Social Democrats are simply out of ideas and out of date. They sprang from the second industrial revolution, when workers eked out miserable and unsafe existences in factories, smelting ores or bashing metals. Just by fighting for the right to safe workplaces and paid leave, Social Democrats did lift many people up. But today, at the dawn of the fourth industrial revolution, that proletariat is disappearing. Unions are shrinking. Jobs are moving into the service sector and the gig economy. Brains are more important than brawn.

The new threat to workers is not from “capitalists” but from artificial intelligence, automation and the Internet of Things. Some very low-wage jobs (such as janitors) are pretty safe. Many high-wage jobs (the creative and brainy ones) will boom. But in between, many professions — especially those based on routines or algorithms, whether in manufacturing or administration — could well disappear. Overall, society will be better off. But for many individuals, the transition will be hell. What about them?

Beats the Social Democrats. Rhetorically, they enjoy calling for “fresh” thinking. So what did Kevin Kuehnert, the allegedly up-and-coming 30-year-old leader of the SPD’s youth organization, come up with? He recently had a brainstorm — wait for it — to collectivize BMW. Bold and visionary, in a bygone century.

Nobody in politics has yet found convincing and comprehensive answers to the twin challenges or our time: reconciling the economy and ecology on a heating planet, and assuring social cohesion as technology first supplements, then competes with, human intelligence. The answers will eventually touch everything from education to taxation, welfare and consumption. There are people probing deeply and curiously into these fields. Just not among the Social Democrats.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Timothy Lavin at tlavin1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a member of Bloomberg's editorial board. He was previously editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.