Why Don't Europe's Oil Majors Sell Assets to Americans?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- U.S. and European oil majors inhabit increasingly different planets. On that of Chevron Corp. and Exxon Mobil Corp., oil demand remains robust despite the acknowledged challenge of climate change. Where BP Plc, Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Total SE live, meanwhile, renewable energy, batteries and electric vehicles are set to overturn oil’s incumbency relatively quickly.

For two decades, the supermajors have been valued on the usual stuff: earnings, leverage, etc. Oil’s enduring primacy wasn’t in question. Now there is a genuine division of worldviews. While the U.S. majors might be characterized as energy transition-curious, the Europeans have shown more commitment both rhetorically and in terms of dollars deployed.

Such disagreement should make for great trading. Private equity sometimes seeks to exploit discounts that open up when companies fall out of favor with public markets (and exploit the reverse when seeking exits). Similarly, if the likes of Shell are signaling some of their resources might never be produced, then those same barrels could hold more value for competitors with a rosier view of oil’s future.

In other words: Shouldn’t the Europeans just sell their oil businesses to the Americans?

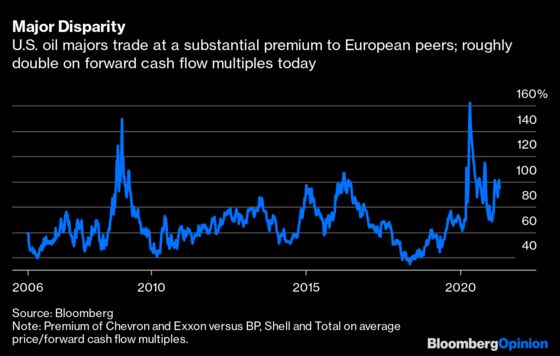

With the best deals, both parties walk away thinking they got one over on the other side. The seller offloads something they guess is past its prime for more than they valued it; and the buyer, thinking the seller misguided or mad, grabs a perceived bargain. So if you think your oilfield has only 10 years left, then someone who thinks it has another 20 should pay up. And U.S. oil majors enjoy a higher relative valuation; meaning, in theory, a lower cost of capital and willingness to bid more.

In practice, wholesale asset trading at this scale looks unrealistic — for now.

For one thing, all oil majors, no matter their provenance, are on probation with investors wary of any hint of empire-building. The U.S. majors’ premium owes much to U.S. stocks trading more richly in general; both U.S. and European oil companies trade at roughly the same discount, about half, to their respective regional markets.

There is also the small matter of managing the energy transition itself. While the European majors pursue different strategies, all are using cash flow from oil and gas to pay for investments in cleantech and fund dividends: Black energy pays for green, as some put it. Their hope is to transform from low single-digit oil multiples to the more rarefied level of an Ørsted A/S (see this). This is logical but extraordinarily ambitious, as oil majors have much to prove in showing they can actually make a decent return on things like wind turbines. In the meantime, oil and gas still pay the bills.

In theory, this shouldn’t matter: If someone will pay more for something than you think it’s worth, then you should sell. But there’s likely less of a gap in transatlantic outlooks than advertised. While long-term views are certainly quite different, the European oil majors, like their U.S. counterparts, probably expect another cycle or three in energy prices through the 2020s at least. While selling an asset can net a nice premium, the seller gives up the implicit option value. You can’t enjoy a windfall from a future oil-price spike if someone else owns the oilfield. For example, BP’s recent better-than-expected quarterly update owes much to its trading business, which is backed by a global portfolio of physical oil and gas assets.

Yet the fundamental difference in worldview remains and will widen. Even if the date of peak oil demand is debatable, each passing year brings it closer. Over time, this should prompt European majors to offload oil (and eventually gas) assets to peers holding a more bullish view of hydrocarbons. Apart from getting more cash from disposals, reducing their weighting to the old business should also make them more credible recipients of ESG dollars.

The best offers would be had, of course, when oil prices are rising. As Europe’s oil majors prepare for the end of the oil age, they could, as ever, use just one more boom.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.