Europe’s Last Land Frontier Is Opening Up

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Ukraine has almost as much agricultural land as France and Germany combined and will finally start allowing it to be bought and sold next year. This is Europe’s last farmland frontier, and the fight over it is going to be messy.

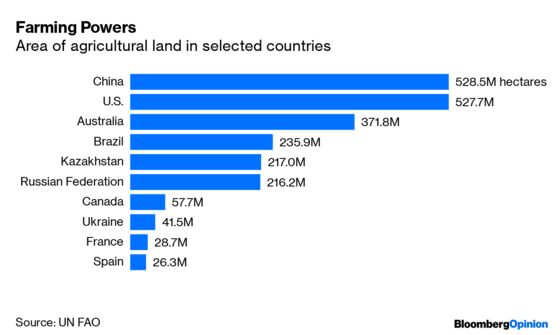

About 17% of Ukraine’s gross domestic product comes from agriculture, the one sector where Ukraine punches above its weight on the global stage. It’s the world’s sixth-biggest wheat exporter, a top-10 supplier of corn and barley, the global leader in sunflower oil exports, and No. 3 in honey, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. It has more farmland than anywhere else in Europe apart from Russia, where much of the land is actually located in Asia, and Ukraine’s nutrient-rich “black earth” soil is of better quality than most of Russia’s.

Ukrainians, however, haven’t been allowed to do much with that land. Out of the total 41.5 million hectares (105 billion acres), only 1.7 million hectares — mostly small plots like private gardens — can be bought and sold. The rest was distributed to former collective farmers after the Soviet Union fell apart, and a moratorium was established on its sale. Russia allowed a market in land in 2003, but Ukrainian legislators have been extending the freeze on sales every year against the persistent advice of international financial institutions. The World Bank estimated in 2017 that lifting the moratorium could boost Ukraine’s annual GDP by 1.5 percentage points, but residual post-Soviet fears that foreigners and oligarchs would buy up all the land made opening the market politically unpopular.

Now, however, new President Volodymyr Zelenskiy is popular enough, and has consolidated enough power in parliament, to finally take the plunge and allow land sales.

“Out of seven million Ukrainians who own land, almost one million citizens have already died” without being able to make much money from their property, Zelenskiy said in a speech touting his reform plan on Thursday.

The government plans to open the land market on Oct. 1, 2020. Ukrainian citizens and Ukrainian-registered companies, regardless of the origin of their beneficial owners (apart from Russians), will be allowed to buy land; to prevent excessive concentration, there will be caps of 0.5% of the total area nationwide and 15% of the total area in a specific region.

But starting official sales isn’t just a matter of snapping one’s fingers once the political will is there. The land sale moratorium spawned a deeply unfair, opaque gray market. The land shares that former collective farmers received in the 1990s often aren’t big enough to farm independently. Since they can’t be sold, banks are reluctant to accept them as collateral. All the nominal owners can do in many cases is lease their land to big agricultural conglomerates at prices about one-fifth as high as in France. Some of the leases are for 50 years or more, and obligations to sell the land after the moratorium is lifted are common.

Five of Ukraine’s top-10 agricultural landholders have already exceeded the government’s planned 0.5% nationwide limit, according to the Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies. The top 10, led by Andriy Verevskiy’s Kernel and Oleg Bakhmatyuk’s UkrLandFarming, work a combined area of about 2.9 million hectares.

Zelenskiy acknowledged the challenges ahead. “A large-scale shadow market has emerged” that “is beneficial not for a small farmer, a simple peasant, but for local so-called land princes,” he said in his speech. Once the law allows official sales, these “princes” will be the best-positioned to turn these holdings into property, and they won’t be easy for any new investors to dislodge.

“We have only one task: to find the optimal model beneficial for ordinary Ukrainians,” Zelenskiy said.

Realizing the nature of the opportunity, some foreign investors have already moved into the market despite its status as a legal gray area. The Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia and the Saudi Grain and Fodder Holding Co., both state entities, are among the biggest investors in Ukrainian land, having acquired large holdings since 2016, according to the Land Matrix, an independent land-monitoring project funded, among others, by the European Union. Some private Western companies, such as U.S.-based NCH Capital Inc., also have acquired sizable holdings. Cargill Inc., the U.S. agricultural giant and a big trader in Ukrainian grain, opted instead to buy a 5% stake in UkrLandFarming in 2014.

New players will inevitably show up as the market’s opening approaches. Once it’s operational, investors will line up for the roughly 11 million hectares that are still state-owned. The government plans to auction them off. But whether the Ukrainian state has the resources to control the market — avoiding monopolization, corruption and turf wars — is uncertain at this point.

“I call on the entire society to watch who will become landowners,” Timofey Milovanov, the recently appointed economy minister, wrote in a Facebook post. “That’s important: It’s not the law that protects, it’s society that protects.” Indeed, without a properly functioning legal system, Ukraine’s active civil society is perhaps the nation’s best hope when it comes to keeping the future land market civilized.

Even if it’s something of a free-for-all, Ukraine can only benefit from allowing land sales. It will boost investment and likely increase agricultural production. It will make many of the current small landowners wealthier and provide considerable privatization revenue to the government. Creating a transparent market that doesn’t benefit oligarchs would be a bonus.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephanie Baker at stebaker@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.