(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In July 2019, more migrants drowned in the Mediterranean than in July 2015, at the height of the refugee crisis – and that despite a dramatically reduced number of arrivals. The 238 deaths are at least partly on the conscience of European politicians; the European Union badly needs a reasonable policy toward the nongovernmental organizations whose rescue ships provide pretty much the only hope to migrants stranded at sea.

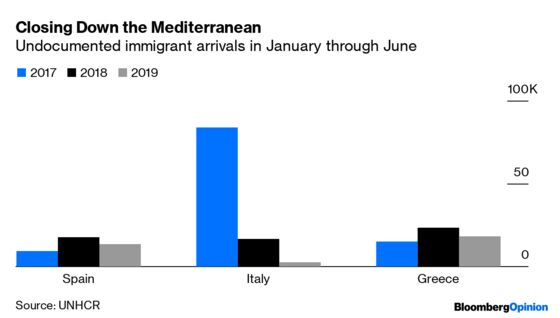

If their goal was to make undocumented migration across the Mediterranean next to impossible, Europeans finally can congratulate themselves. Die Welt, the German conservative daily, recently trumpeted “The End of the Mediterranean Route.” As of this year, deals exist that keep migrants from making each of the three possible crossings: From Morocco to Spain (the two countries signed an agreement in February, allowing Spain’s sea rescue services to take people back to Moroccan ports), from Libya to Italy (an EU deal with the former country’s weak government has existed since 2017, with EU funding for the Libyan coast guard so it can turn back migrant boats) and from Turkey to Greece (the EU has been paying the Turkish government to keep asylum seekers from crossing since 2016, although Turkey announced last month that it was “suspending” the deal).

Something else that’s been different this year was Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini’s crackdown on Mediterranean migration. As far as arrival numbers go, it’s been a huge success.

In other words, it has taken the EU about four years to build a system of agreements that brings the number of migrants arriving from Turkey and North Africa to a manageable minimum. If one believes in the distinction between genuine refugees and economic migrants, its construction makes perfect sense: These days, very few of the migrants crossing the Mediterranean are from war-ravaged countries where their lives would be directly endangered, so not many of them stand a realistic chance of asylum. Moroccans, Tunisians, Algerians, Ivoiriens, Congolese – under EU member states’ laws, they have nothing to seek on European shores.

Having built up its defenses, the EU stopped its naval search-and-rescue activities in the Mediterranean. Operation Sophia, which used to include them, is now limited to flights over the sea to monitor human trafficking. Though this effort often was dismissed as “organized hypocrisy” because it was meant primarily to deter crossings rather than pick up shipwrecked migrants, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration last month called on the EU to restart it.

That’s because no framework of bilateral deals can prevent the unwanted migrants from coming, because the hardship they face in their home countries is worse than anything they may be forced to endure in Europe. And if they keep coming, they will keep drowning; someone needs to pick them up at sea.

At this point, just a handful of nongovernmental humanitarian organizations specialize in this. Germany-based Sea-Watch e.V. runs two rescue ships, the Sea-Watch 3 and the Mare Jonio. Another one, Sea-Eye e.V., has one, the Alan Kurdi, named after the Syrian toddler found drowned on a Turkish beach in 2015. The Spanish charity Open Arms operates a ship of the same name. Doctors Without Borders and SOS Mediterranee, both multinational organizations, pick up migrants with the Ocean Viking. That, as of this month, is the extent of help available to those trying to make the crossing.

It’s not the smallest number of NGO ships that have simultaneously plied the waters mainly between Libya and Italy, but the situation changes rapidly because the rescue vessels keep getting detained.

Italy, of course, is at the forefront of the fight thanks to Salvini, who earlier this month succeeded in pushing through the Italian parliament a decree hiking fines for unauthorized docking from 50,000 euros ($55,600) to 1 million euros. But Malta, Greece and Spain also have started various legal proceedings, including criminal ones, against the migrant-rescuing charities. The NGOs, in other words, are being harassed by EU member states on the Mediterranean frontier.

The worst ordeals take place when the rescue ships try to dock somewhere in Europe with migrants on board. The Open Arms spent 19 days at sea, unable to dock anywhere, before Italy finally allowed the 80 migrants it had on board to disembark last week. The Ocean Viking was refused entry to several European ports, including for refueling, for 14 days before European governments worked out – also last week – an ad hoc deal to divide up the 356 migrants it had rescued.

Such case-by-case arrangements are the order of the day in the absence of a permanent EU-based mechanism. Last month, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that 14 EU member states had agreed to a “solidarity mechanism” proposed by France and Germany, but only eight countries actually confirmed they were on board; six countries – France, Germany, Luxembourg, Ireland, Portugal and Romania – took the Ocean Viking’s “passengers,” but the process was anything but “quick” and “automatic” as Macron promised.

While politicians bargain over every additional migrant, the NGO ships’ captains acquire rock star status. Carola Rackete and Pia Klemp, who work for Sea-Watch, are household names in their native Germany, frequently interviewed by national media and handed prestigious awards. Last week, Klemp turned down the highest honor the city of Paris can bestow, the Medaille Grand Vermeil, accusing France of mistreating asylum-seekers. “We do not need authorities deciding about who is a 'hero' and who is 'illegal',” she wrote on Facebook. “In fact they are in no position to make this call, because we are all equal.”

Both star captains are of the radical left, firm believers in the supreme value of solidarity – but also in other things with which most reasonable people would disagree. Rackete, for example, has said some of the migrants she picks up are climate refugees whom Europe has a duty to accept. Yet people like Rackete and Klemp are today the only ones with the courage and the sense of responsibility to pull desperate people out of the water.

Their vessels are not “migrant taxis” for human traffickers, as Salvini has dubbed them. The respect the captains inspire is a sign that a large part of the European civil society isn’t about to accept policies that leave people stranded at sea, whether or not they have valid immigration papers. The optics of making life hard for the rescuers are horrible for the EU as a value-based organization.

If the EU as a bloc is unable to agree on migration reform because of staunch opposition from the likes of Salvini and the nationalist Eastern European governments, there should be at least a coalition of the willing within the EU that would prevent the NGO ships from languishing at sea for weeks while governments work out who should take how many people.

That means designating several ports where the migrants can be brought so they can be sent on without delay to host states, according to a predetermined quota. This would have nothing to do with normalizing undocumented immigration: Those who embark on the Mediterranean journey today, given all the protections the EU has put in place, are truly desperate people. None of them are risking their lives for fun. They are doubly desperate when their leaky vessels sink far from shore, and extremely lucky when a rescue ship picks them up. The 839 of them who have drowned so far this year had no such luck.

The size of the coalition of the willing doesn’t really matter; even five or six wealthy European nations can afford to take a few hundred people a year each. Those countries that refuse to do it today won’t be governed by nationalists forever; one day they, too, will have governments that’ll be ashamed not to participate. In the meantime, if a coalition of the willing does exist, it should act willing rather than reluctant – these migrants have already suffered enough.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.